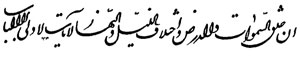

See, in the creation of the heavens and the earth and the alternation of day and night there are signs for those with insight.

Sūra 3:190

SACRED SPACE

‘The Muslim lives in a space defined by the sound of the Koran.’ Thus writes S. H. Nasr to point to the situation of the Muslim believer.1 He is certainly right, and yet Islamic tradition has known and still knows, as do all religions, a good number of places which are or seem to be endowed with special blessing power and which then serve in literature as symbols of the human experience of ‘coming home’.

Thinking of places with such sacred power, one can begin with the cave. Humankind has been fascinated by caves for millennia, as prehistory and history prove, and Islam continued in this respect, though from a somewhat different vantage point. Is not the cave singled out by the very name of Sūra 18, al-Kahf, ‘The Cave’, a Sūra in which—along with other stories—the Seven Sleepers, the aṣḥāb al-kahf, are mentioned at some length? The seven pious youths ‘and the eighth with them was their dog’ (Sūra 18:22) have turned in popular Islam into protective spirits whose names, and especially that of their dog Qiṭmīr, written on amulets, carry baraka with them.2

In the historical context, it is well known that the Prophet Muhammad received his initial revelation in a cave on Mt Hira where he used to retire for meditation. It was in the solitude of this place that he was blessed with the first auditions which forced him to go into the world and preach what he had learned: the constant change between the khalwa, the lonely place of meditation in the dark cave, undisturbed in his concentration upon God, and the jilwa, the need and duty to promulgate the Divine word that he had heard, was to remain the model for the Muslims—a spiritual movement of whose necessity Iqbāl reminds the believers of our time.

Yet, there is a second cave in the Prophet's biography: the cave where he found shelter during his hegira from Mecca to Medina. And again, after re-emerging from the mysteriously protected place where he, as Sufi tradition has it, introduced his friend Abū Bakr into the mysteries of the silent dhikr, his life as a political leader in Medina began: once more, he undertook the way out of the khalwa of meditation into the jilwa of preaching and acting.

The Prophet's example of retiring into the cave was imitated by a number of mystics who lived for long periods in caves. The extremely narrow cave in which Sharafuddīn Manērī of Bihar (d. 1381) spent several decades of his life is only one of the numerous examples of this pious custom; Muhammad Ghawth Gwaliorī (d. 1562) also belongs to the Sufis who, year after year, performed their meditation in a cave, to emerge in the end filled with overwhelming spiritual energy. The experience of the arba‘īn, chilla, khalwat, forty days’ meditation in a narrow, dark room or a subterranean place, belongs here as well. The intimacy of the experience of God's proximity in such a khalwa could lead the pious to address Him in prayer as ‘Oh Cave of them that seek refuge!’3

The cave is difficult to reach for men and animals, and is hence safe. But when one lives on the plains, the sacred space has to be separated from the profane environment by an enclosure (one remembers here that the Latin term sanctus is derived from sancīre, ‘to limit, enclose’, and hence ‘make sacred’), and so the cult takes place in a spot removed from the ordinary space, which keeps away not only animals but also, as was thought, demons. Lonely prayer places in Sind and Balochistan are surrounded by simple thorn hedges (as are some shrines in the desert),4 and it is probably not too far-fetched to think that the border of the prayer rug also serves as a kind of enclosure which marks the praying person's inviolable ‘sanctuary’—even though the whole world can serve as a prayer place.

More important is the house, the man-made dwelling-place which serves both for protection and as a sanctuary: in Sind and Balochistan, the house of the wadērō, the big landlord, could serve as a shelter for women accused of immorality or other transgressions.5 However, the concept of ‘house’ has a much wider range: the ‘House of Islam’, dār al-islām, is the area which, as Walter Braune says aptly, is built on five pillars and in which the believers live in safety, while the dār al-ḥarb, ‘the abode of war’, is the world outside the ideal home of the believers.6 To enlarge this ‘house’ is incumbent upon the community, so that finally the whole world may become a ‘House of Islam’.

And not only that. In religious language, the house is one of the most frequently-used metaphors for the human heart—a house that has to be cleansed by constantly using the ‘broom of lā’, that is, the beginning of the profession of faith, lā ilāha illā Allāh, ‘There is no deity but God’. Only when the house is clean and no dust of profane thought has remained can the dulcis hospis animae, the ‘sweet guest of the soul’, enter and dwell in it. The Baghdadian Sufi an-Nūrī (d. 907) used this metaphor,7 and Mawlānā Rūmī sang in one of his most famous stories in the Mathnawī (M I 3,056–63):

A man knocked at the door of his beloved.

‘Who are you, trusted one?’ thus asked the friend.

He answered: ‘I!’ The friend said: ‘Go away—

Here is no place for people raw and crude!’

What, then, could cook the raw and rescue him

But separation's fire and exile's flame?

The poor man went to travel a whole year

And burnt in separation from his friend.

And he matured, was cooked and burnt, returned

And carefully approached the friend's abode.

He walked around it now in cautious fear,

Lest from his lips unfitting words appear.

The friend called out: ‘Who is there at my door?’

The answer: ‘You—you dear are at the door!’

He said: ‘Come in, now that you are all I—

There is no room in this house for two ‘I's!’

In order to enter the precincts of the house, one has to cross the threshold, the liminal place par excellence that cuts off the sacred from the profane. It is therefore a rule that one must not step on the threshold: as the bride in Muslim India is carried over it into her new home, the devotee is warned not to step on the threshold of the master's house or the shrine. To enhance the religio-magic power of the threshold, one may sacrifice a sheep over it or at least sprinkle some blood on it.8

While Muslims carefully avoid touching the threshold with their feet, which are sullied by the dust of the profane world, one often sees men and women at shrines devoutly kissing the step that will lead them into the sacred presence of the saint. ‘One should rub one's face on the threshold like a broom’, says a Turkish handbook of religious etiquette.9 The threshold's sanctity is also attested by dream exegesis: threshold and door mean, in the dream, women, i.e. the sacred, ḥarīm, part of the house.10

Since the door or gate allows the visitor to enter the private, ‘sacred’ sphere, gates of mosques and shrines are often huge and impressively decorated. Alternatively, shrines may have an extremely low door which forces the entering person to bow down humbly; again, there are narrow doors through which the visitor squeezes himself in the hope of obtaining blessings. A typical example is the bihtshtīdarwāza, the ‘paradisiacal door’ in Farīduddīn Ganj-i shakar's shrine in Pakpattan, where, during the anniversary of his death, thousands of pilgrims strive to enter into the saint's presence in order to secure entrance to Paradise.

The door opens into the sacred space, and the Muslim knows that ‘God is the Opener of the doors’, mufattiḥ al-abwāb, as He is called in a favourite invocation, for it is He who can open the doors of His mercy or generosity, not forgetting the gates of Paradise.11 In later Sufism, the seven principal Divine Names are even called hadana, ‘doorkeepers’. Metaphorically, the concept of the door or gate is important by its use in the well-known ḥadīth deeply loved especially in Shia tradition, in which the Prophet states: ‘I am the city of wisdom and ‘Alī is its gate’ (AM no. 90), that is, only through ‘Alī's mediation can one understand the Prophet's true teaching. As the gate, bāb, can be the person through whom the believer may be led into the Divine presence, it is logical that the spiritual guide could also be considered, or consider himself, to be The Gate, the Bāb. This claim was voiced most prominently by Mirzā Muḥammad ‘Alī of Tabriz, which led to the emergence of a new religious movement, Babism, in early nineteenth-century Iran.

After entering the house, one finds the high seat, ṣadr, or the throne, sarīr, both of which possess special baraka; and anyone who has seen an old Pakistani woman throning on her bed and ruling the large household knows that this is more man simply an elevated place: the seat carries authority with it. But those lowest in rank, or most modest, will sit in the ‘place of the sandals’, that is, where the shoes are left close to the entrance.

In the Arabic tradition, the hearth plays no major role, while among the Turks the fireplace, ocak, as is typical of peoples from northern climates, was the veritable centre of the house, and the term ocak is used in modern Turkey to denote the true centre of the community.

The Muslim house boasts carpets and rugs, pile-woven or flat-woven, and the rug can be as important as the high seat, the place for the master of the house. The tide sajjāda nishīn or pōst nishīn for the person who ‘sits on the mat’ of a Sufi master, i.e. his true successor, conveys an impression of the rug's importance. The numerous flying carpets in Oriental folk tales seem to translate the subconscious feeling that the carpet is something very special.

There is also a place with negative power in or close to the house: the privy, which is regarded as a dwelling-place of unclean and dangerous spirits and is therefore avoided by angels. The bath itself, however, sometimes decorated with paintings plays an important role in connection with the strict rules of ritual purity.12

Larger and higher than the normal house is the citadel or fortress, ideally built in a circular shape. If the heart can be imagined as a house for the Divine Beloved, it can also be seen as a fortress with several ramparts—again one of Nūrī's images, which prefigures St Teresa's Interior Casde.13 For the Sufis, the shahāda became the stronghold and citadel in which they felt safe from the temptations of the world, as though the rampart and moats of sacred words helped them to survive in the inner chamber, which could be compared to the h, the last letter of the word Allāh.14 Is not God a fortress, ḥiṣn, and a stronghold, ḥirz?15 The word ḥirz is also used as a name of one type of protective prayers and litanies, while the term taḥṣīn, literally ‘to make into a fortress’, can be used for the religio-magic circumambulation of villages or groups of people to protect themselves against enemies.

The sacred space par excellence in Islam seems to be the mosque, and many visitors—Rudolf Otto, S. H. Nasr, Martin Lings, Frithjof Schuon and others—have emphasized the ‘feeling of the Numinous’, the experience of otherworldliness when standing in one of the great mosques in North Africa or Turkey.16 These buildings were, as they felt, perfect expressions of the emptiness which is waiting to be filled with Divine blessing, that is the experience of the human being, poor (faqīr) as he or she is, in the presence of the All-Rich, al-ghaniy.

However, the mosque was first no more than a house, a building in which instruction and legal business were conducted as well: it was and is not—unlike me church—a consecrated building. Its name, masjid, is derived from sajada, ‘to prostrate’, meaning ‘place of prostration’. A mosque for larger groups, where believers could gather on Friday for the midday prayer with following sermon, is called jāmi‘, ‘the collecting one’. In the early Middle Ages, up to around AD 900, only one jami‘ was found in each city; the minbar, the pulpit from which the preacher gives his short sermon, was the distinctive mark of a city, as was the minaret. In later times, when mosques proliferated, a certain distance was still kept between the major mosques, or a new jāmi‘ was built only when the first one, too small for the growing number of the faithful, could not possibly be enlarged.

To build a mosque is a highly meritorious act, and a tradition which is frequently quoted in India (especially in Bengal) states: ‘Who builds a mosque for God, be it as small as the nest of a qaṭā bird, for him God will build a house in Paradise’.17 The paradisiacal recompense can also be granted to someone else: when the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror (1449–81) erected a mosque in the recently conquered city of Istanbul in remembrance of his father, the intention was the same as offering prayers for the well-being of the deceased monarch's soul.18 Popular piety therefore claims that a mosque is like a boat of salvation or, even more fancifully, that it will be transformed into a white camel to carry its founder on Doomsday across the ṣirāṭ-bridge.19

The increasing feeling of the sanctity of the mosque is understood from the custom of using its precincts for istikhāra, that is, performing two prayer cycles and then sleeping in the mosque in the hope of being guided by a dream. And Turkish calligraphers would collect the soot produced by the oil lamps in, for example, the Süleymaniye mosque in Istanbul to use it as an ingredient of their ink which, they felt, would thus carry some of the mosque's baraka with it.

The shapes of mosques vary according to the architectural styles of the different countries, and from simple mud mosques in Africa to pagoda-like structures in China almost every form is found. Mosques in Gujarat, with their narrow rows of highly decorated pillars, resemble Hindu temples, and for the Western observer the Turkish mosque with its central dome and the elegant needle-like minarets seems to be the paragon of the concept of ‘mosque’, although large mosques with wide prayer halls or endless rows of naves belong to a much earlier, classical period (Samarra, Cordoba).

But whatever the outward shape, every mosque has a miḥrāb, a niche pointing to the direction of Mecca, which could be shaped, again, according to the material available and to the artistic taste of the builder. Often, words from Sūra 3:37 are written around the miḥrāb: ‘Whenever Zakariya entered the miḥrāb…’, for the term is used for the place where the young Mary dwelt and was mysteriously nourished by the Lord. What appear to be the most unusual and impressive miḥrābs in the world of Islam are located in the Indian subcontinent: the miḥrāb of the Great Mosque in Bijapur/Deccan, built in 1635 and measuring six to seven metres across, is completely decorated in a highly sophisticated style with à-jour inscriptions, half-relief, and colourful niches in gold and red. The Faisal Mosque in Islamabad, completed some 350 years later, boasts as its miḥrāb the likeness of an opened copy of the Koran in white marble, inscribed in ‘medieval’ Kufi calligraphy with verses from Sūra 55, Ar-Raḥmān, ‘The Merciful’.

While the miḥrāb is common to masjid and jāmi‘s, the jāmi‘ alone contains an elevated pulpit for the Friday sermon, usually three steps high; larger odd numbers of steps can be found in vast buildings. This minbar, again, can consist of the most diverse materials; the artistically carved wooden minbars of medieval Egypt and Anatolia are worthy of mention. The preacher, who stands on the minbar, briefly sits down between the two parts of his address in memory of the Prophet's sitting on the first minbar, a simple platform.20

One may find a few huge candlestands, and the floor is usually covered with prayer rugs. A stand for the Koran and sometimes boxes in thirty parts for the thirty juz’ of the Koran belong to the necessary items in the mosque; a clock that shows the times of prayer is a more recent addition. The walls are plain, for too much colour or decoration might distract the praying person's eye and mind. They are covered with tiles (as in Iran and Turkey) or with white marble; if there is any decoration, then it is only calligraphy, whether Koranic verses or the name of God in enormous letters, or sometimes also the names of the four rightly guided caliphs (as in the Aya Sofya in Istanbul).

The minaret, again connected only with the jāmi‘, and built in diverse shapes according to local traditions, was sometimes conceived of as a tower of victory, the visible sign of Islam's presence in a newly conquered area: the Qutub Minar in Delhi from the early thirteenth century is a good example of this type of minaret. For those who loved esoteric meaning, it was not difficult to connect it, owing to its shape, with the letter alif that is always taken to symbolize the Aḥad, the One God. And was not the building of a mosque in a newly acquired territory, as it were, a new ‘brick’ in the extension of the House of Islam?

In some mosques, a special corner is reserved for women; in others (often in Turkey), women are expected to pray on the balcony-like gallery. In state capitals, one may find a maqṣūra, a special enclosure for the rulers.

Another sacred place of major importance is the burial place of a saintly person. The Prophet himself, according to one tradition, prohibited visits to tombs, while according to another he suggested turning to ‘the people of the graves’ when facing difficulties.21 Visits to tombs and cemeteries became a common practice and offered rare opportunities for an outing to many women. The Prophet's warning against frequenting the tombs was reinforced in the nineteenth century by the Wahhabis in Central Arabia, who did not even honour the sanctity of the Prophet's own mausoleum.

Among the places with special baraka are, understandably, the tombs of the martyrs of faith such as Kerbela, Najaf and Mashhad. Kerbela, where the Prophet's grandson Ḥusayn ibn ‘Alī fell in fighting against the Omayyad forces in 680, is in the Shia world coterminous with ‘utter tragedy’, and its name was explained as a combination of karb and barā;, ‘grief and affliction’. The earth of Kerbela, with its strong baraka, is still ‘exported’ to other countries (see above, p. 5). When Muḥarram is celebrated in Shia cities, especially in India, a place called ‘Kerbela’ is chosen close to a tank or a river; there the tābūts, replicas of Ḥusayn's sarcophagus, are submerged at the end of the ritual. To make people partake in the baraka of the sacred places, one can even call children after them: Najaf or Nazaf Khan, and Madīnakhan, appear in the Indian subcontinent,

A mausoleum often develops from a simple heap of stones, and even a great Sufi like Gēsūdarāz (d. 1422) tells, tongue in cheek, the story of me travellers whose dog died on the road and was buried. They marked the faithful creature's tomb, and when they returned to the same place after some years, they found that a flourishing town had developed around the ‘saint's’ burial place.22 Even more obscene anecdotes about the growth of a pilgrimage centre are not uncommon in Muslim literature.

The tombs of saints are highly venerated.23 People will throng at the tomb's doors or windows to make vows; they hang rags on nearby trees or on the window grill, or post petitions on the wall hoping for the saint's intercession, and as the saint's baraka increases after he has left this world, people want to be buried near to him: that is how the enormous cemeteries in the Islamic world came into existence. The cemetery of Makli Hill near Thatta in Sind is credited with the presence of 125,000 saints; the Qarāfa in Cairo allows a survey of hundreds of years of Muslim cultural history in Egypt, and, during a walk through the hilly cemetery of Khuldābād, ‘Abode of Eternity’ near Daulatabad in the northern Deccan, one gains a comprehensive survey of the entire history of the Deccan from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries, for poets, emperors, scholars and politicians rest peacefully in this lovely place.24

Rulers erected their mausoleums usually during their lifetime and surrounded their future burial site with charitable foundations to ensure benefits for their souls. When the last Mamluk sultan Qanṣauh al-Ghawrī's dead body was never found on the battlefield of Marj Dabiq in August 1516, the historian Ibn Iyās attributed this strange event to the fact that the ruler had illegally appropriated the marble of someone else's mausoleum and used it to embellish his own mausoleum ‘and God did not allow him to be buried in it, and therein is a sign for those who have eyes to see’.25 Often, the mausoleums of rulers were surrounded by vast gardens, sometimes divided by canals so as to resemble the gardens of Paradise ‘under which rivers flow’ and to give the deceased, as it were, a foretaste of heavenly bliss.

In cases when a famous person's burial place is unknown, or when Muslims want to gain some of his baraka in their own village or town, they erect a maqām, a memorial. In the Fertile Crescent, one finds a number of maqāms in places where ‘All's camel allegedly stopped.26 But more prominent are the maqāms of saints, for example, places devoted to the memory of Bāyezīd Bisṭāmī, who died in 874 in northern Iran but is venerated in Zousfana in the High Adas as well as in Ghittagong in Bangladesh (and probably in other places as well). The Turkish bard Yunus Emre (d. 1321) has maqāms in at least seven Anatolian towns, and the city of Mazar-i Sharif in Afghanistan grew around an alleged tomb of ‘Alī. The most recent example of a ‘maqām’ is that of Muḥammad Iqbāl (buried in Lahore) in the garden near Mawlānā Rūmī's mausoleum in Konya, erected by the Turks, to underline the spiritual connection between the two religious poets.

Often, the actual mausoleum of a saintly person is connected with the dargāh, the seat of the mystical guide who continues the saint's work. To stay for a few days at a dargāh, as a waiter or servant, can make the visitor a special recipient of Divine grace, and many people avail themselves as much of the living baraka of the ‘master of the prayer rug’ or his assistants as of the healing power of a tank or well close to the shrine. The shrine serves as a sanctuary, and people may swear innocence before it; some regular visitors may even be able to ‘see’ the saint.27

The master who resides in the dargāh has a spiritual territory, wilāyat, and it was customary that he would assign to his khalīfa, substitute or vicegerent, a certain area over which his influence would extent; the borders of the spiritual territories of two khalīfas, or, more complicated, of khalīfas of two different masters were strictly defined and had by no means to be transgressed. The protecting power of the saint was thought to work only inside his territory.28

Shrines and dargāhs were and still are usually open to non-Muslims; in some of them, women are not admitted inside (similarly, men are excluded from women saints’ shrines). As humans have apparently always prayed at the same places, there is a certain continuity in the use of such places, as if a special baraka were inherent in this or that spot. That is well known in the Jewish-Christian-Muslim sequence in Near Eastern sanctuaries, and holds true in many cases also for Indian Muslim and formerly Hindu places of worship. Therefore, the borders between religions often seem blurred in the dargāhs and shrines—certainly one of the valid reasons for the aversion of traditionalist orthodox Muslims to saint-worship. It has been rightly stated for India that ‘While the mosque distinguishes and separates Muslims and Hindu, the dargāh tends to bring them together’.29

Other sacred places in the Islamic world are, for example, the Ismaili Jamaatkhana, to which the outsider is only rarely given access even at times outside the service; the dā'ira of the Indian Mahdawis, which is mainly devoted to dhikr rather man to ritual prayer; or the imāmbārah of the Twelver Shia, where; the implements of me Muḥarram processions are kept and which the Shia rulers, especially in Lucknow, Hyderabad/Deccan and Bengal, built in the hope of heavenly reward. There are, further, the different types of Sufi convents such as the ribāṭ, whose name conveys the idea of fortification and fighting at the frontier but becomes in the Maghrib a true dervish centre founded by a shaykh and frequented by his followers. The taqiya, in Turkish tekke, contrasts with the large khānqāh (the Khānqāh Siryāqūs near medieval Cairo is a glorious example of such an institution)30 and the dargāh, a term mainly used in India, and the solitary master would perhaps dwell in a zāwiya, ‘corner’, a term which, again in the Maghrib, is used to mean rather a hospice for Sufis. The use of names for these institutions varied in different times and different countries, but one thing is common to all Sufi institutions: none of them is a ‘consecrated’ building. For the pious, they assumed a sacred quality owing to the master's and the dervishes’ presence.

When the Muslim speaks of the ‘two sacred places’ (al-ḥaramān; accusative and genitive al-ḥaramayn), he means Mecca and Medina. The word ḥaram, from the same root as ḥarām, ‘prohibited’, designates the place where anything profane is excluded, as the ḥarīm, the place reserved for women, is accessible only for the maḥram, a male member of the family who is related to the inmates. To enter the heart of the sanctuary, in this case the precincts of the Kaaba in Mecca, one is required to put on the iḥrām, the garment that obliges the pilgrim to observe a number of taboos such as avoidance of sex, of cutting one's hair or of paring one's nails. This is valid not only during the season of the ḥajj in the last lunar month but also during the ‘smaller pilgrimage’, the ‘umra, which can be performed at any time.

In the sacred precincts, no animal may be hunted or killed, and Iqbāl alludes to this prohibition by admonishing his co-religionists to return spiritually to Mecca and gather in the protective shade in the Kaaba because ‘no gazelle’, that is, no living being must be hunted there while they, oblivious to their spiritual centre, have become an easy prey for the non-Muslim hunters—and non-Muslims are excluded from the sacred place, Mecca.31

The name of Mecca is connected, in general thought, with a great assembly-place, and one can encounter, in the West, expressions like ‘the Mecca of gamblers’ or ‘of racing cars’. For this reason, Muslims now prefer to spell the city's name as Makkah to distinguish it from these strange and appalling definitions.

The city of Mecca, Muhammad's home town, is situated between two ranges of hills and formerly housed an ancient Arabian sanctuary. The Koran (Sūra 42:7) calls the place umm al-qurā, ‘the mother of the cities’ (hence the name of its university), and numerous legends have grown around this place from where, as Muslims believe, the creation of the Earth began. Thus, as the praying Muslim turns to Mecca whence the Earth was expanded, he turns spiritually to the centre of truth, the source of all spirituality. Mecca's unique role is emphasized in a proverb in which its inhabitants proudly claim that a person who sleeps at Mecca is equal to someone worshipping God in another place.32

The central sanctuary, the Kaaba, blesses the city with its presence: it appears as an omphalos, the navel of the earth,33 and is, as pious people believe, situated exactly opposite the heavenly Kaaba in the seventh heaven. During the deluge, the Meccan Kaaba was taken into heaven, where Noah's Ark surrounded it seven times. As for the heavenly Kaaba, it is constantly circumambulated by angels whose movements the pilgrim should remember while performing the ṭawāf, ‘circumambulation’ around the earthly Kaaba. But sometimes, as legend tells, the Kaaba itself comes to turn around visiting saints such as the great Sufi woman Rābi'a (d. 801), or wanders to a Sufi in faraway lands.34 The Koran (Sūra 2:125ff.) speaks of Abraham's building or restoring the Kaaba; and, when the Prophet reconquered Mecca in 630, he cleaned the building of all the idols, whose number is given as 360, which may point to an old astral cult connected with the sanctuary (the moon god Hubal is well known from pre-Islamic times).

The Kaaba is an almost cubic stone building measuring 12 m² and 15 m high; it is usually covered with the black kiswa, and many poets have compared this black veiled structure with a longed-for bride whom one wants to reach and kiss.35 Thus, comparisons of the kissing of the black stone in the Kaaba's south-eastern corner with kissing the black beauty spot or the lips of the beloved are common in Persian poetry.

As Mecca and the Kaaba are, for the pious, certainly the most sacred place on Earth to which the living and the dead turn, one should not spit or stretch out one's legs in the direction of the Kaaba, nor perform bodily needs in its direction. After death, the believer should be buried lying on his right side with his face turned towards the Kaaba.

As every Muslim has to direct his or her position towards the Kaaba during the five daily prayers (Sūra 2:144), it became important for Muslim mathematicians and astronomers to enable believers to find the right direction, qibla, when travelling by land or sea; lately, they have even discussed the problem of how to determine the qibla while travelling in a spaceship. Mathematical and geographical research developed refined methods of finding the correct direction; in later times, small compasses facilitated this.36 But it was not always easy to determine the exact position of the prayer niche, miḥrāb, in a mosque, especially when the mosque was built in an already crowded quarter and one had to adjust the structure of the building with one face following the alignment of the street while the other showed the direction towards Mecca. There were different ways of achieving the correct result, so that one may even find slightly varying directions in one and the same city.37 Legends, mainly from India, tell how a saint's prayer could correct the position of the miḥrāb when an architect had miscalculated it. That was a useful miracle, for the Muslims are indeed called the ahl al-qibla, ‘those that turn towards the qibla’, and warnings are issued about talking against the ahl al-qibla, for they are all united by turning to the same centre of prayer-life. Poets loved to compare the beautifully arched eyebrows of their beloved to a miḥrāb—was not Adam, the first human being, a qibla before whom the angels prostrated and through whom one could find the way to the Divine beauty?38 It is therefore not surprising that the Persian line

Mā qibla rāst kardīm bi-simṭ-i kajkulāhī

We have directed our prayer direction towards the one sporting his cap awry

became commonplace in later Persian and Persianate poetry.39

For the mystically minded poets knew that the Kaaba in Mecca, central as it is, is still a mere sign—the ka‘ba-i gil, ‘Kaaba of clay’, is often juxtaposed with the ka‘ba-i dil, ‘the Kaaba of the heart’—and everyone has his or her own qibla, the place of worship to which one turns intentionally or unintentionally. For qibla became a general term for the place on which one concentrated one's attention: when a calligrapher is called with the honorific tide qiblat al-kuttāb, it means that he is the person to whom everyone in the writing profession turns in admiration. Rūmī describes, towards the end of his life, the different qiblas to whom humans turn instead of looking towards Mecca, the central direction of worship:

The Kaaba for the spirits

and Gabriel: the Sidra-tree,

The qibla of the glutton,

that is the table-cloth.

The qibla for the gnostic:

the light of union with God,

The qibla of the reason,

philosophizing: vain thought!

The qibla of the ascetic:

the beneficent God,

The qibla of the greedy:

a purse that's filled with gold.

The qibla of those who look at

true meaning, is patience fine,

The qibla of those who worship

the form: an image of stone.

The qibla of those esoterics

is He, the Lord of Grace,

The qibla of these exoterists

is but a woman's face…

(M VI 1,896f.)

Despite such psychologically insightful verses, Mecca was and remained the veritable centre of Islamic piety. Moreover, it is not only the place to which to turn in prayer and which to visit during the pilgrimage; it has also inspired innumerable people in their religious achievement. The great medieval theologian, al-Juwaynī (d. 1085), was honoured by the title imām al-ḥaramayn because of his prolonged exile in the sacred places. Pilgrims, particularly scholars who stayed for months, even for years in Mecca, were inspired to compose their most important works there. Zamakhsharī (d. 1144), with the honorific title Jār Allāh, ‘God's neighbour’, as result of his prolonged sojourn in Mecca, wrote his comprehensive commentary on the Koran in this place, and at the beginning of the following century Ibn ‘Arabīi received the initial but comprehensive inspiration for his voluminous Futūḥāt al-makkiyya, ‘The Meccan Openings’, while circumambulating the Kaaba.40 Again, centuries later, the Indian reformer Shāh Walīullāh (d. 1762) wrote his Fuyūz al-ḥaramayn, ‘The Effusions of Grace from the Two Sacred Places’ under the impression of his sojourn in the sacred cities.

The stay in Mecca had certainly an ‘Arabicizing’ influence on pilgrims from foreign countries, and numerous reform movements in North and West Africa, Bengal and Central Asia were sparked off when Muslim leaders came to Mecca, where they found what seemed to them true Islam but which often contrasted with the ‘Islam’ in their homeland, which now appeared to them utterly polluted by the pernicious influences of popular customs and pre-Islamic practices. They then felt compelled to reform Islam at home as a result of their stay in Mecca.

Another noteworthy aspect of Mecca's central position was the understanding that he who rules over Mecca and Medina is the rightful caliph—hence the claim of the Ottomans who conquered Mamluk Egypt and the areas under its dominion, including the Hijaz, in 1516-17 and thus became the overlords of the ḥaramayn. But the mystics often voiced the opinion that ‘Mecca is of this world, faith is not of this world’, and that God can be found everywhere and that His presence is not restricted to the Kaaba.

The role of the second sacred place, Medina, was increasingly emphasized in the later Middle Ages. After all, it was the city where the Prophet was buried, and with the growing glorification of the Prophet and the deepening of mystical love for him and trust in him, Medina gained in status.

The role of Medina in the history of Islam cannot be overstated. The Prophet's hegira in 622 to this town, that only after some time was to become a Muslim, ‘home’, forms the beginning of the Muslim calendar, for now the Prophet's revelations had to be put into practice and create political and juridical foundations for the fast-growing community of believers. Besides this practical side of the hegira, medieval mystics have seen it as a subtle hint to the fact that one has to leave one's home to find superior glory; and for a modernist like Iqbāl, the hegira shows that one should not cling to narrow, earthbound, nationalist concepts.41 The Muslims who migrated from India to the newly-created Pakistan in the wake of the partition in 1947 called themselves muhājir, ‘one who has participated in the hegira’ from ‘infidel Hindustan’ to the new home where they hoped to practise their faith without difficulties, and modern North American Muslims may find consolation in the thought that they, like the companions of the Prophet, have left their former home and found a new place in not-yet-Muslim America.

For most pilgrims, it is their dream to visit the Prophet's tomb, the rawḍa, in Medina in connection with the pilgrimage, and the Saudi authorities, despite their aversion to ‘tomb-worship’, allow these visits.42 Pictures of the Rawḍa, as of the Kaaba, decorate many houses; printed on calendars, woven into rugs, painted on wails, they convey the blessing of the Prophet's spiritual presence. The sanctity of Medina is understood from the medieval belief that the plague never touches this city.

Poetry in honour of Medina seems to develop from the late thirteenth century, the first major representative of this genre being Ibn Daqīq al-‘Id (d. 1302).43 The greater the distance between the poet's country and Medina, the more emotional he waxes:

More beautiful than all the flowers are the flowers of Medina…

and, as Jāmī thinks, the angels make their rosaries from the kernels of Medina's dates.44 It makes hardly any difference whether the poet in Anatolia around 1300 sings:

If my Lord would kindly grant it,

I would go there, weeping, weeping,

and Muhammad in Medina

I would see there, weeping, weeping,

or whether he lives in eighteenth-century Sind, like ‘Abdur Ra'ūf Bhattī, whose unassuming poem has the refrain:

In the luminous Medina, could I be there, always there…45

For Medina is al-madīna al-mumawwara, the luminous city, and the pious imagine that there is a column of light over the Rawḍa, as the modern Sudanese writer, al-Fayṭūrī, states:

Over the Prophet's bones, every speck of dust is a pillar of light.46

In Indo-Pakistan, poetical anthologies with the title Madīna kā ṣadaqa, ‘Pious alms for Medina’, are available in cheap prints, and Iqbāl wrote, close to the end of his life:

Old as I am, I'm going to Medina

to sing my song there, full of love and joy,

just like a bird who in the desert night

spreads out his wings when dunking of his nest.47

Besides the ḥaramayn, the city of Jerusalem is surrounded with special sanctity, for it was not only the place on whose rock, as mentioned earlier (p. 2), all the previous prophets had rested, but also, more importantly, the first qibla of the Muslims.48 Only after the hegira was the prayer direction changed to Mecca (Sūra 2:144). Connected also with the Prophet's heavenly journey and with mythological tales about the events on Doomsday, when Isrāfīl will blow the trumpet from there, Jerusalem holds pride of place in the hearts of the Muslims, and many early ascetics spent some time there.49

The orientation to the Kaaba is certainly central for the Muslim, but it is not only the direction in prayer mat plays a great role in his life and thought. One has to remember the importance given to the right side as well. The term ‘right’, yamīn, belongs to a root with connotations of felicity and happiness; the right side is the ‘right’, prosperous side. One eats with the right hand (or rather with its first three fingers), while the left hand is unclean, being used for purification after defilement. One should enter a room with the right foot first, and sleep if possible on the right side to ensure happy and good dreams. On the Day of Judgment, the Book of Actions will be given in the sinners’ left hands, and they are the ‘people of the left’ (Sūra 56:41). When Ibn ‘Abbās states that Paradise is to the right side of the Throne and Hell to its left, then popular belief has it that during ritual prayer the Prophet and Gabriel are standing at the praying person's right side while Hell is waiting at his/her left.50 The importance of the right side is attested not only in surnames like Dhū ‘l-yamīnayn, ‘someone with two right hands’ for an ambidextrous and successful individual, but also in the idea mat ‘God has two right hands’.51 Thus, the orientation towards the right is a time-honoured and generally accepted fact. Yet there are other spatial peculiarities as well.

The Koran emphasizes that East and West belong to God (Sūra 2:115) and that true piety does not consist of turning to the East or West (Sūra 2:177); it mentions also the wondrous olive tree that is ‘neither from the East nor from the West’ (Sūra 24:35). Yet, as the right side was thought to be connected with positive values, it seems that an ‘orientation’ in the true sense of the word, that is ‘turning to the East’, was well known to Muslim thinkers from early days despite the different directions in which the qibla had to be faced in the expanding empire. The worn-out juxtaposition of the material West and the spiritual East is not a modern invention: Suhrawardī the Master of Illumination spoke of the ghurbat al-gharbiyya, the ‘western exile’ where the soul is pining and whence she should return to the luminous East. Persian poets sometimes confront Qandahar in the East and Qairouwan in the West, combing the latter name with qīr, ‘tar’, because the dark West makes them think of pitch-black misery. Similarly, the Dakhni Urdu poet Wajhī (d. after 1610) located, in his story Sab ras, King Intellect in the West and King Love in the East, while Sindhi folk poets like to speak of the ‘journey eastwards’ of the spiritual seeker although both their traditional goals of pilgrimage, Mecca and the ancient Hindu cave of Hinglaj, are situated west of Sind. One wonders whether the language called Pūrabī, ‘eastern’, in which God addressed the Delhi mystic Niẓāmuddīn Awliyā, was indeed the Purabi dialect of Hindwi or whether it points to a ‘spiritual language’ in which he heard the Divine Beloved speak.

The ‘Orient of lights’, the place where the light rises, appears sometimes also as Yemen, which in Suhrawardī's work represents the true home of spirituality because the ‘country on the right hand’ was the home of Uways al-Qaranī, who embraced Islam without ever meeting the Prophet and concerning whose spirituality the Prophet said, as legend tells: ‘I feel the bream of the Merciful coming from Yemen’. Ḥikma yamaniyya, ‘Yemenite wisdom’, and ḥikma yūnāniyya, ‘Greek philosophy’, contrast, as do intuitive gnosis and intellectual approach, as do East and West.52

Not only this ‘Morgenlandfahrt’ of the medieval Muslim thinkers is fascinating, but also the way in which some of them transformed a geographical concept into its opposite. India, which in most cases is the land of ‘black infidelity’, became in a certain current of Persian poetry the home of the soul. ‘The elephant saw India in his dream’ that means that the soul was reminded of its primordial home whence it had been carried away to live—again—in Western exile. And the steppes of Asia, where the musk-deer lives and moonlike beauties dwell, could become at times a landscape of the soul—where the soul, guided by the scent of the musk-deer, finds its eternal home.53

Again, the concept of the quṭb, the Pole or Axis, the central figure in the hierarchy of the saints, points to the importance of the upward orientation, as Henry Corbin has lucidly shown: the polar star, thought to be located opposite the Kaaba, is the guiding light for the traveller.54

On a different level, one meets the concept of sacred space in attempts of medieval Sufis—especially in the tradition of Ibn ‘Arabī—to map the spiritual world and describe the strata of Divine manifestations through which the inaccessible Divine Essence reveals Itself. One usually speaks in descending sequence of ‘ālam al-lāhūt, ‘the world of divinity’, ‘ālam al-jabarūt, ‘the world of power’, ‘ālam al-malakūt, ‘the realm of the Kingdom’, and ‘ālam an-nāsūt, ‘the realm of human beings’. In certain cases, the highest level beyond the ‘ālam al-lāhūt is thought to be the ‘ālam al-hāhūt, the ‘Divine Ipseity’ as symbolized in the final h of the word Allāh. Very frequently, the ‘ālam al-mithāl, ‘the realm of imagination’, mundus imaginalis, is placed between the world of the heavenly Kingdom and that of humanity, where it constitutes so to speak a reservoir of possibilities which await realization and can be called down by the spiritual ambition of the saint.

One also sees attempts to chart the Otherworld, for the Koranic mention of various stages in Paradise, such as ‘illiyūn (Sūra 83:18, 19), jannat ‘adan (Sūra 15:45 et al.) and the like, invited searching souls to develop an increasingly complicated celestial geography. Again, the main contribution in this field is owed to Ibn ‘Arabī and his followers. And as late as 1960, a Turkish thinker produced a lengthy study about the geography of Hell.

The importance of sacred space and place is reflected in the emphasis which Islam plays on the concept of the road, a theme that can be called central in Islamic thought.55 Does not the Muslim pray with the words of the Koran: ihdinā ‘ṣ-ṣirāṭa ‘l-mustaqīm, ‘Guide us on the straight path!’ (Sūra 1:6)? This petition from the Fātiḥa, repeated millions of times every day around the world, has lent the title ‘Islam, the straight Path’ to more than one study on Islamic piety (and one may add that titles of books that contain Arabic terms like nahj or minhāj, both meaning ‘path, right way’, are often used for religious works).

God guides, and He can let people go astray in the desert (aḍalla), but the straight path is manifested—so one can say—in the sharī‘a, a term usually (and rightly) translated as ‘religious law’. Its basic meaning is, however, ‘the road that leads to a water course or fountain’, that is, the only road on which the traveller can reach the water that is needed to survive; for in the desert, it is incumbent on everyone to follow the well-established path lest one perish in the wilderness—and the sharī‘a offers this guidance.

The concept of ṭarīqa, ‘path’, which expresses the mystical path in general and has become the normal term for Sufi fraternities, belongs to the same cluster of images, with the understanding that the narrow path, ṭarīqa, branches out from the highway. There can be no ṭarīqa without the sharī‘a.56

In this connection, one may also think of the frequent use of the word sabīl, ‘way’, in expressions like ‘to do something’, ‘to fight’, or ‘to give alms’ fi sabīl Allāh, ‘in the way of God’, that is, in the right direction, guided by the knowledge that one's action is God-pleasing and will result in positive values. The feeling that the establishment of fountains and the like is particularly useful fi sabīl Allāh is the reason why fountains near mosques and in the streets are often simply called sabīl, literally ‘way’. Finally, the term for the legal school which Muslims adhere to, and according to whose rules Muslims judge and are judged, is madhhab, ‘way on which one walks’, a term often used in modern parlance for ‘religious persuasion’.

But the ‘way’ is also very real: the pilgrimage to Mecca, ḥajj, is one of the five pillars of Islam. Legend tells that Gabriel taught the rites of the ḥajj to Adam and Eve,57 and the decisive ritual was set by the Prophet's last pilgrimage shortly before he passed away. The pilgrimage has served numerous writers as a symbol of the soul's journey towards the longed-for goal, ‘the city of God at the other end of the road’ (John Masefield).58 One's entire life could be seen as a movement through the maqāmāt, the stations on the journey, or the stations of the heart, in the hope of reaching the faraway Beloved. The pilgrims’ progress is regulated on the normal level by the sharī‘a and, for the Sufis, by the ṭarīqa; it is a dangerous undertaking whose external and internal difficulties and hardships are often described. The long journeys through deserts or beyond the sea made the ḥajj in former times a very heavy duty; many pilgrims died from fatigue, illness, Bedouin attacks and shipwreck; and yet, as Indonesian pilgrims state, these long, strenuous journeys served much better as a preparation for the final experience of ‘reaching the goal’ than the modern brief, rather comfortable air travels.59 And as the pilgrimage to Mecca is fraught with dangers and hardships, thus the inner pilgrimage requires uninterrupted wakefulness. It is a journey through the spaces of the soul which the sālik, the wayfarer, traverses, day after day, year after year, for, as Ibn ‘Aṭā Allāh says:

Were there not the spaces of the soul, there would be no journey from man to God.

The mystics have always asked, as did Mawlānā Rūmī:

Oh, you who've gone on pilgrimage—where are you? Where, o where?

Here, here is the Beloved—O come now, come, o come!

Your friend, he is your neighbour; he is next to your wall—

You, erring in the desert—what air of love is this?

(D no. 648)

In this process, the actual landscapes are transformed into landscapes of the soul: when in the old Sindhi story of Sassui Punhun the lovesick young woman runs through the deserts and steep rocks, braving all kinds of dangers, the poet makes us understand that this is a perfect symbol of the difficulties that the soul has to overcome on her path to God.60

The topos of the journey and the path predate Islamic times: the central part of the ancient Arabic qaṣīda describes most eloquently the poet-hero's journey on his strong camel or his swift horse through the desert, and the theme of such a journey was taken over by later poets. Thus Ibn al-Fāriḍ's (d. 1235) major poem, the Tā'iyya, is officially called Naẓm as-sulūk, ‘The Order of the Progressing Journey’. Slightly later, Rūmī sang of the necessity of travelling in a poem whose first line he took over from Anvarī (d. around 1190):

Oh, if a tree could wander and move with foot and wings!

It would not suffer the axe-blows and not the pain of saws!

(D no. 1,142)

Painful though the separation from home may be, it is necessary for one's development: the raindrop leaves the ocean to return as a pearl; the Prophet left Mecca to become a ruler in Medina and return victoriously.

It is the Prophet's experience not only in the hegira but even more in his nightly journey, isrāi‘raj, that offered the Muslims a superb model for the spiritual journey. The brief allusion in Sūra 17:1 was elaborated and enlarged in; the course of the centuries and lovingly embellished; the Persian painters in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries represented the wondrous event in glorious pictures, often with moving details, and almost every later Persian or Turkish epic contains a poetical description of the Prophet's mi‘rāj. The last epic in the long list of works inspired by the account of the mi‘rāj is Iqbāl's Jāvīdnāma (1932), which combines the different traditional strands of the motif and weaves them into a colourful fabric of modern Islamic thought. The assumption that the kitāb al-mi‘rāj, Arabic tales about the Prophet's nightly journey through Heaven and Hell, has influenced Dante's Divine Comedy to a certain extent seems to be well established thanks to Enrico Cerulli's research.61

The soul's journey usually traverses seven stations; the eighth may be the ‘heavenly hearth of Hurqalyā’. Henry Corbin has pointed out how the concept of the quṭb, the mystical ‘axis’ or ‘pole’, is closely connected with the theme of the upward journey, for it is the point of orientation for the soul on its ascent from the Western exile.

The ascent through the seven valleys, well known in Christianity, is most beautifully symbolized in ‘Aṭṭār's Persian epic Manṭiq uṭ-ṭayr, which sings of the journey of the thirty soul birds towards the Sīmurgh at the end of the world. Like many other thinkers, ‘Aṭṭār too found that the arrival at what looked like the end of the road is only a mere beginning, for ‘when the journey to God ends, the journey in God begins’.

There are two journeys, one to God and one in God, for God is infinite and eternal. And how could there be an end for the journey of the soul that has reached His presence?62

But we are faced with a dilemma. God is always described as lā-makān, ‘there where no place is’, or as being in nā-kujā-abād, ‘Where there is no Where’ and yet the Koran describes Him as the One who ‘is upright on the Throne’ (Sūra 7:54, 13:2 et al.) and states that His Throne ‘embraces the whole universe’ (Sūra 2:255). His Throne is beyond Heaven and Earth and what is in them, and yet He, who is closer to mankind than the jugular vein (Sūra 50:16), dwells in the innermost sanctuary of the human heart.

The experience of the journey to God and into His depths is expressed in a ḥadīth. the Prophet, speaking of his own mi‘rāj, admonished his companions: ‘Do not prefer me to Yūnus ibn Mattā because my journey is into the height and his journey is into the depths’. For there are two ways to reach the Divine: the journey upwards to Mt Qāf and beyond, and the journey into the ocean of one's soul. The same ‘Aṭṭār who so eloquently describes the birds’ journey to Mt Qāf in his Manṭiq uṭ-ṭayr has devoted another work, the Muṣībatnāma, to the journey that leads the seeker through the forty stations of seclusion into the ocean of his soul.63

Both ways are legitimate—the one into the heights of Divine glory where the Divine light permeates everything and becomes invisible owing to its radiance, and the way into the dark abyss where all words fail and the soul loses itself in sheer ecstasy, drowned in the fathomless ocean of God.

Both ways also seem correct when one thinks of the concept of orientation in Islam: the correct direction to the qibla, indicated by the Kaaba in Mecca, is binding for everyone, and yet the Muslim also knows that ‘Whithersoever ye turn, there is the Face of God’ (Sūra 2:115).

SACRED TIME64

At the end of the road, the carpet of time and space is rolled up. But before this point and this moment is reached, we observe the same apparent paradox that we encountered concerning God's ‘place’ and ‘placelessness’ when dealing with time and timelessness in Islamic thought.

Time measures our lives, and each religion has its own sacred times: times in which the mystery that was there at the beginning is re-enacted; festivities which are taken out of the normal flow of daily life and thus carry humans into a different dimension; sacred seasons; and sacred days and hours.

For the Muslim, the history of salvation (Heilsgeschichte) begins with Muhammad, as his essence is the first thing created by God and, as mystics would claim, thus precedes the ‘first man’ Adam. His appearance in time after the long ages in which earlier prophets taught God's commands constitutes the climax of human history; in him, the fullness of time is reached. This conviction helps to explain the Muslim's constant longing for the Prophet's time, for no other time could have been or could ever become so blessed as the years that he, bearer of the Divine Word, was acting on Earth. For this reason, all ‘reform movements’ are bound to reorient themselves back to the Prophet's time.

People have looked for an explanation why Muhammad appeared just around the turn of the sixth to the seventh century AD, and Ibn ‘Arabī found out that the Prophet entered history in the sign of Libra, which means that he inaugurated a new age in the sign of justice, that is, he struck the balance between the legalism of Moses and the mildness of Jesus.65

Historically speaking, Muslim time-consciousness begins with the hegira which, as already mentioned, means the practical realization of the contents of the revelation. Furthermore, an important new beginning was made as a purely lunar year was introduced, which entailed a complete break with old Semitic fertility cults connected with the solar year and its seasons. To be sure, the solar year continued to be used for financial purposes such as taxation, as the yield of the crops was dependent upon the seasons and could not be harmonized with the lunar calendar, in which, contrary to earlier systems, no intercalation was permitted.

The month begins when the crescent moon is sighted by two reliable, honest witnesses. Although the appearance of the first slim crescent can be mathematically determined in advance, the prescription of actually observing the moon still remains valid. The crescent was thus able to become the favourite symbol of Islamic culture.66

Nevertheless, some rites are still celebrated according to the solar calendar. The best-known one is Nawrūz, the Persian New Year at the vernal equinox, which was and still is central in the Persianate world but which was accepted, to a certain degree, also by the Arabs. Some feasts of local saints again follow the solar calendar, for example that of Aḥmad al-Badawī in Tanta, Egypt, whose dates are connected with fertility, which means, in Egypt, with the rising of the Nile.

Other popular measures of time may have been in use in various parts of the Islamic world; thus, Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje mentions for the late nineteenth century a Hadramauti solar year which consisted of twenty-eight parts with thirteen days each; the twenty-eight parts corresponded one by one to the station in which the moon rises.67 These lunar mansions were, as he states, well known among the people. Indeed, the importance given to the lunar mansions is a fascinating aspect of Muslim culture, and numerous popular sayings and superstitions express the widespread acquaintance with these concepts, which are echoed in high literature. Thus, one should avoid bloodletting when the moon is in Libra, and ‘moon in Scorpio’ is the worst possible, most disastrous combination, as both Muslim writers and European observers tell.68 The poetical genre of bārahmāsa, ‘Twelve Months’ poems’, in the Indo-Pakistani vernaculars shows a curious shifting from Indian to Muslim and recently even to Western months.69

Feasts carry a special power with them, and therefore humans behave differently on festive days, beginning with the custom of sporting new garments. One may perform supererogative acts of piety, distribute alms, or share food and sweets. That is particularly true for the two great feasts in the Muslim world which are based on Koranic sanction: one is the ‘īd ul-fiṭr at the end of Ramadan (Turkish şeker bayramĭ, ‘sugar feast’), the other one the ‘īd an-nahr or ‘id al-aḍḥā (Turkish qurban bayramĭ), when the sacrificial animal is slaughtered during the ḥajj on the tenth day of the last lunar month.70

Ramadan is the most sacred time of the year, for during this month the first revelation of the Koran took place. The gates of Hell are closed, the gates of Paradise open. The laylat al-qadr, the Night of Might (Sūra 97), is ‘better than a thousand months’ it is thought to be one of the last odd nights of the month, probably the twenty-seventh. Many pious people therefore spend the last ten or so days of the month in seclusion or in the mosque, and even those who do not fast generally may try to fast at least on the first and during the last ten days for the sake of blessing. The laylat al-qadr is thought to be filled with light, a light that appears to a few blessed people who excel by their devotion.71

Although a fasting day, ‘āshūrā, was institutionalized at an early stage in Mecca,72 now a whole month is devoted to fasting (Sūra 2:185), a hard discipline which requires strong intention and is particularly difficult when it happens to fall in the hot season, for the fasting Muslim is not allowed a single sip of water (if possible, one even avoids swallowing one's saliva) between dawn, when one can discern between a black and a white thread, and the completion of sunset. Nor are food, smoking, sex, perfume or injections permitted during daytime; exemptions are possible for weak, travelling or fighting people and menstruating and pregnant women; but either the lost days have to be made up for, or other penitences such as feeding a certain number of poor are required, following exact regulations. It seems that the fasting along with the community, and the festive fast-breaking, ifṭār, along with others, make the discipline for all its difficulties more joyful than an outsider can judge. Ramadan is a problem for northern countries, when summer days stretch for more than twenty hours and where many believers miss the wider communal support that they would enjoy in a Muslim country. According to some fatwās, the Muslim in such faraway northern areas (and that would be valid for southern areas as well, e.g. Muslims in southern Chile) could break the fast at the time when it is broken in the next Muslim country; that would be Turkey or North Africa for Europeans. It was also claimed that because fasting is not required during war, and hard labour in factories or agriculture is a ‘war against poverty’, these workers should be exempt from this religious duty; but this suggestion by President Bourguiba of Tunisia was not favourably met with.

After breaking the fast with an odd number of dates and some water, the pious Muslim will perform the evening prayer, then eat, then perform another set of prayers, the so-called tarāwīḥ, which comprise usually twenty, sometimes twenty-three rak‘ah (cycles). The nights used to be formerly devoted to amusements and joyful entertainment; before the night is over, one may eat a light meal (saḥūr or saḥriÒ), and then formulate the intention for another day of fasting. The ‘īd ul-fiṭr is celebrated with great joy, but differences in sighting the moon may cause the feast to be celebrated with a day's difference in the same country or in faraway areas, although the sighting of the moon in Mecca is now broadcast all over the Muslim world.

The laylat al-qadr is filled with light because the world was illuminated by the revelation of God's Word, but the laylat al-mīlād, the birth of the Prophet, is equally luminous, as popular and mystical piety have it, quite in harmony with the general phenomenon that the ‘birth of the saviour’ in the history of religions is surrounded by light.73 The exact date of the Prophet's birth is unknown; the twelfth day of Rabi‘al-awwal, the third lunar month, is actually the date of his death, and in some areas, such as in Pakistan's North-West Frontier, it is still remembered as such (bārah wafāt) without displaying the joyful aspects of the birthday. Celebrations of the birthday are known first from Fatimid times, for the Fatimids (969–1171), claiming descent from the Prophet's daughter Fāṭima, had a dynastic interest in celebrating at least in courtly circles their ancestor's birthday. Around 1200, the celebrations were already widespread and elaborate, as can be understood from Ibn Khallikān's account of the mawlid, ‘birthday’ in Arbela (Irbil) in 1207. Praise-songs were composed on this occasion, and the use of candles and illuminations became popular—a custom to which the traditionalists objected because of its similarity to Christian festivities. Lately, however, the imaginative poems in honour of the Prophet's birth, as they are known from Turkey to East Africa and India from the fourteenth century onwards, were discarded in many countries because their romanticism seemed incompatible with a modern sober mind, and instead of the great ‘Welcome’ which all of Nature sings to the new-born Prophet (as expressed in Süleyman Çelebi's Turkish mevlûd), the Prophet's ethical and political achievements are emphasized. But in Cairo, Muslims continue to celebrate the day with great joy, and the sugar-dolls, called ‘bride of the mawlid’, are still sold and enchant children.

The two ‘īd are firmly rooted in Koranic tradition, and the celebration of the Prophet's birthday was a corollary of the increasing veneration which was felt for the ‘best of mankind’, who brought the final revelation. Another feast has no Koranic roots and yet is connected with the Prophet who, according to some ḥadīth, emphasized its importance. It was apparently celebrated in the early Middle Ages, for it is mentioned in Sanā'i's (d. 1131) Persian poetry. This is the laylat al-barā'a (shab-i barat in Persian), the night of the full moon of the eighth lunar month, Sha‘bān. Special sweets are made and, as usual for such nights, firecrackers and fireworks are used. Additional prayers are recommended, for example 100 rak‘a with ten recitations of Sūra 112 in each rak‘a; for this night is something like a New Year's Eve: God destines—so many people believe—mankind's fate for the next twelve months, and, according to a delightful belief, the angels put on file the notes which they have written about each human's action during the last twelve months. In Lebanon, the middle of Sha‘bān was celebrated as the mawlūd, the birthday, of all those saints whose actual memorial days were unknown, while among the Shia it is regarded as Imam al-Mahdī's birthday.74 Sanā'ī not only mentions the shab-i barāt as a special sign of grace for the Prophet but also singles out the ‘white nights’, that is, the nights of the full moon in general; the first three days of the four sacred months—Muḥarram, Rajab, Ramaḍān and Dhu ‘l-ḥijja—were also surrounded by a special sanctity; fasting was recommended at these times.75

In the Shia community, more sacred days are known, such as ‘Alī's birthday (13 Rajab) and the Day of Ghadīr Khum (18 Dhu ‘l-ḥijja), when the Prophet invested ‘Alī as his successor. Most important, however, is the month of Muḥarram, especially its first ten days. Processions begin, people go to the majlis, which are meetings (separated for men and women, of course) with standards, flags and votive offerings placed in a corner, and the story of Ḥusayn's suffering in Kerbela is recited in poetry and prose with increasing intensity day by day. Pious Shiites follow the sufferings of the imam, the death of the small children, the wailing of the women and the final martyrdom of Ḥusayn and his family and friends with ever-heightened empathy, almost like the Christians who live through the mysteries of the Holy Week.76

In the processions on 10 Muḥarram, tābūts are carried, replicas of the sarcophagus of Ḥusayn. These are very high structures (5–6 m) made of wood or paper, veritable works of art in whose preparation the pious compete from the beginning of Muḥarram. A white horse is also led in the procession in case the Mahdi should suddenly appear (see above, p. 25). Everyone wants to participate in these processions and the general atmosphere of mourning. S. H. Manto's Urdu short story Kālī Shalwār, ‘The black shalwar’, tells of a prostitute's desire for the black trousers worn during Muḥarram (for Muslims avoid wearing colourful garments, jewellery and make-up); in Ahmadabad in Gujarat, the prostitutes have a special day for taking part in the celebration, during which they abstain completely from their usual activities. For Muslims know that weeping for Ḥusayn is necessary for one's salvation—even though the idea is not theologically founded.

The Muḥarram processions with flagellation and even fire-walking have turned in some areas into something akin to a carnival: in Hyderabad/Deccan, one finds buffoons dancing with the procession, and little boys may serve— usually owing to their parent's vow—as Ḥusayn kā majnūn, ‘Ḥusayn's madman’ fumigation with fragrant woods is also practised.77 As in other popular festivities, such as anniversaries of a saint's death, ‘urs, the limits of normal behaviour can disappear, the borders between different classes and groups of people can be lifted, and everyone is carried away in the waves of enthusiasm, if not frenzy, that tear apart the sober rhythm of normal life.

Special food is connected with Muḥarram: on ‘Ashūrā Day, the actual death of Ḥusayn, Muslims prepare a dish called ‘āshūrā, which consists of grains, raisins and numerous other ingredients to remind the pious of the last meal which the poor members of the Prophet's family prepared from the few edibles that they could scratch together. To send a bowl of ‘āshūrā to one's neighbours was customary in Turkey and the countries east of it; now, ‘āshūrā appears as a delicious everyday dessert on the menu of many Turkish restaurants.

Poets loved to sing of the tragedy of Kerbela, and the genre of marthiya, threnody, had its highest development at the Shia courts of India, especially Lucknow; it ranges from simple lullabies for the dying six-month-old baby ‘Alī Aṣghar (thus in Golconda in the seventeenth century) to the famous marthiyas of Anīs (d. 1874) and Dabīr (d. 1875). The latter two excelled in long poems of the type musaddas, six-lined stanzas, which enabled them to describe the gruesome details most accurately at epical length. To this day, a good recitation of an Urdu marthiya moves the participants in a majlis to tears, and such recitations attract thousands of Indo-Pakistanis, for example in London.

In Iran, poets have also devoted poetry to the event of Kerbela. Most impressive among their ballads is Qā'ānī's elegy in the rhetorical form of ‘question and answer’, which begins with the lines;

What's raining?—Blood!—Who?—The eye.—How?—Day and night!

—Why?—From grief!—What grief?—The grief of the monarch of

Kerbela…78

This form points to the tendency in Iran to dramatize the event of Kerbela. There, the art of ta‘ziya, a kind of passion play, occupies a prominent place.79 In these plays, the sufferings of Imam Ḥusayn and his family are placed at the centre of the entire universal history, to become an integral part of salvation history. Not historical truth but the metahistorical importance of Ḥusayn's suffering is at the base of this ta‘ziya, in which the most incongruous protagonists are brought together to become aware of Ḥusayn's sacrifice; Adam, Mawlānā Rūmī, the martyr-mystic al-Ḥallāj and many others are woven into the fascinating fabric of these plays which centre around an event that took place at a well-defined moment in history yet seems to belong to a different dimension of time.80 The poets, especially the folk poets, have therefore been accused of mentioning how Ḥasan, ‘Alī's elder son, entered the battlefield along with his brother Ḥusayn, although in reality he had died (probably poisoned) some eleven years earlier; but, for the poets, both appear as ‘princes’ or ‘bridegrooms’ of Kerbela.

While Muḥarram is generally observed in the Shia community, another tendency among some Indian Shiites was not only to commemorate Kerbela but also to celebrate all the death anniversaries as well as birthdays of the twelve imams with dramatic performances: eye-witnesses at the court of Lucknow in the 1830s describe such uninterrupted festivities and tell with amazement that the king's favourite elephant was trained to mourn Imam Ḥusayn during Muḥarram with long-drawn-out trumpetings; Wāh Ḥusaynaa, wāāh Ḥusaynaa, Wāh Ḥusaayyin…81

Much more in the general line of festive days are the celebrations of saints’ anniversaries, called ‘urs, ‘wedding’, because the saint's soul has reached the Divine Beloved's presence. Tens and even hundreds of thousands of pilgrims arrive from various parts of the country or, as in the case of Mu‘īnuddīn Chishtī (d. 1236) in Ajmer, even in special trains from Pakistan which, for the occasion, are allowed to cross the otherwise closed border. Common prayer, the singing of hymns and, last but not least, the participation in the common meals which are distributed weld them into one great family (the ‘urs at Ajmer has lately been described in detail).82 The religious events can go together with less religious aspects; the shrine of Lāl Shahbāz Qalandar in Sehwan, Sind, still bears traces in the cult of its long-forgotten past as a Shiva sanctuary, and the ‘urs of Sālār Mas‘ūd in Bahraich reminds the visitor not only of the spiritual marriage of the young hero's soul with God but also of his nuptials with his bride, Zahra Bībī.83 Many people regard a visit on the anniversary of ‘their’ special saint as almost equal to a pilgrimage to Mecca.84 (To visit Mawlānā Rūmī's mausoleum in Konya seven times equals one ḥajj—so they claim in Konya.) Muslims like to visit mausoleums and cemeteries on Fridays before the noon prayer, and in general the gates are always open to welcome visitors. The days of the ‘urs of each saint are carefully printed in small calendars in India and Pakistan, although for the traditionalist the celebration of saints’ anniversaries is nothing short of paganism, and the legalistically-minded ‘ulamā tried time and again to curtail these customs.

For the pious Muslim, almost every month has special characteristics. While in Muḥarram Muslims think of the martyrdom of Ḥusayn and avoid wedding feasts (even among Sunnis), the second month, Ṣafar, is considered unlucky because the Prophet's terminal illness began on its last Wednesday, and he supposedly said that he would bless the one who gave him news that Ṣafar was over.

In Rabī ‘al-awwal, the Prophet's anniversary is celebrated, while the next month, Rabī’ ath-thānī, is devoted—at least for Sufi-minded Muslims—to the memory of ‘Abdul Qādir Gīlānī (d. 1166), the founder of the Qadiriyya ṭariqa; hence in Indo-Pakistan it is simply called gyārhrinñ or yārhinñ, ‘the eleventh’, because ‘Abdul Qādir's anniversary falls on the eleventh of the month.

Rajab, the seventh lunar month, is connected with the Prophet's heavenly journey, mi‘rāj, which took place, according to tradition, on the twenty-seventh. The so-called raghā'ib nights at its beginning are especially blessed. This month is preferable for the smaller pilgrimage, the ‘umra, which, however, is permitted at any time except during the days of the ḥajj.

Sha‘bān is the month of the laylat al-barā'a: and some pious people have claimed that the letters of its very name point to five noble qualities of the Prophet: sh: sharaf, dignity, honour; ‘ayn: ‘uluw, eminence; b: birr, goodness; atif: ulfat, friendship, affection; n: nūr, light. It is also related that he used to fast in Sha‘bān as a preparation for Ramaḍān. The following Ramaḍān, as the fasting moon, and finally the last month, Dhū ‘l-ḥijja, as the time of pilgrimage, are considered blessed everywhere.

In this connection, it is revealing to have a look at a list of days during which the Muslim sipahis in India (especially in the Deccan) were given home leave by the British in the nineteenth century: during the Muḥarram festivities, on the last Wednesday of Ṣafar, on the Prophet's death anniversary (i.e. 12 Rabī‘al-awwal), on ‘Abdul Qādir's ‘urs, and on the ‘urs of Zinda Shāh Madār, as well as on the memorial day of Mawlā ‘Alī and of Gēsūdarāz, the great Chishti saint of Gulbarga (d. 1422). Lists from other parts of British India may have included other saints’ days.

But not only ‘sacred’ days which are taken out of the normal flow of time by dint of their blessing power are observed; rather, each day has its peculiarities because it is connected with planetary influences, angels, colours and scents, as one can understand from Niẓāmī's Persian epic Haft Paykar. If any sober critic feels compelled to accuse Niẓāmī of poetical exaggeration, he should turn to the works of famous Muslim scholars such as the traditionist and theologian Jalāluddīn as-Suyūṭī (d. 1505) in Cairo and the leading ḥadīth scholar in seventeenth-century India, ‘Abdul Ḥaqq Muḥaddith Dihlawī (d. 1645), for both of them—like many others before and after them—have composed books about the properties of the days of the week. As God created Adam on Friday from the clay that the angel ‘Azra'il collected by force from the earth, Friday is the best day of the week. Hud and Abraham, so it is said, were born on a Friday (the latter incidentally on 10 Muḥarram!), and Gabriel gave Solomon his miraculous ring on Friday, as Kisā'ī tells. Thus, the central position of the day on which the congregation is supposed to gather at noon in the mosque is duly singled out, although in classical times Friday, in contrast to the Sabbath and Sunday, was not considered a full holiday. Only comparatively recently have some Muslim states declared it the weekly holiday, while Sunday is a working day in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, for example. On Friday, so Muslims believe, there is an hour during which God answers all prayers—but the exact moment is unknown to mortals.85

Monday is the day of the Prophet's birth as well as of his triumphal entrance into Mecca in 630—hence it is a most auspicious day, while Tuesday is considered unlucky, for God created all unpleasant things on Tuesday. Thursday is a good day for travelling, for military undertakings and also for fasting86 (as a preparation for Friday, for the day begins at its eve: jum‘a rāt, ‘Friday night’, corresponds to the night between Thursday and Friday).

The scholars detected auspicious days for shaving, for measuring and for putting on new clothes; in short, one might organize one's whole life in accordance with the aspects of certain days. It is well known that the Mughal emperor Humāyūn (1530–56) fastidiously clung to the rules of the auspicious and inauspicious days and hours and would allow people to visit him in this or that capacity or for specific kinds of work only according to the right hour of the right day.87

Most blessed are, in any case, the early morning hours (the Koran urges Muslims in Sūra 11:114 to pray at the ends of the day and at night). Therefore the merchant will sell the first item at a special price to partake in this blessing; the first customer's arrival will positively determine the whole day.

The hours themselves were fixed in accordance with the prayer times, whose greatest possible extension was exactly to be measured by the length of the shadow cast by the praying person. Now, modern clocks facilitate the exact determination of the time, which, in any case, is marked by the mu'adhdhin's call from the minaret. The Westerner who may be used to calling the time between approximately 3 and 6 p.m. ‘afternoon’ will have to learn that, for the Turks, ‘afternoon’, marks rather the hours between noon prayer and mid-afternoon prayer, ‘aṣr.

When speaking about time-consciousness in Islam, one tends to regard time as linear, which is typical of ‘prophetic religions’: time begins with creation, the Yesterday, dūsh, of Persian poets, and leads to the Day of Judgment, the Tomorrow of the Koran (cf. Sūra 54:26). But this linear time changes in a certain way into a cyclical movement, that is, ‘the journey of God's servants from the place of beginning to the place of return’, as Sanā'ī and Najmuddīn Dāyā Rāzī called their books concerning human beings’ progress.88 Mystics would see it as a journey from ’ adam, ‘not-being’, into the second ’ adam, the unfathomable Divine Essence. Later Sufis have spoken of the arc of descent from the Divine origin to the manifestation of humanity and back in the arc of ascent into the Divine homeland, under whatever image (rose-garden, ocean, reed-bed) it may have been symbolized.

A complete development of cyclical time, however, has been offered by the Ismailis, to whose system Henry Corbin has devoted a number of studies—the seven cycles of prophets and their nāṭiqs, ‘speakers’, represent the cyclical movement in universal history.89