And We shall show them Our signs in the horizons and in themselves.

Sūra 41:53

In which language does the modern Muslim express himself, his faith and his ideals? That is a question not only of philology but also of a general attitude, visible in modern art, audible in modern music, reflected in modern literature and thus a question that concerns every aspect of life.1

The use of broadcasting not only for the recitation of the Koran but also for giving legal decisions, fatwā (as is the case for example in Yemen); the fact that in Cairo a walī heals by telephone every Friday between 9 and 11 a.m.; and the reactions to spaceships and computer technology make us ask: how can the modern Muslim, faced with the overwhelming success of Western technology, find a way to accept and cope with the time-honoured teachings of traditional tafsīr and ḥadīth in modern times? Is not a science, ‘ilm, which is basically geared toward a preparation of human beings for the Hereafter, obsolete and to be discarded?

To silence opponents, sceptics and worried souls, it is often proclaimed that Islam is self-sufficient, that it owes nothing to other religions and philosophical systems but rather that it endowed the West with scholarly discoveries during the dark ‘Middle Ages’; and that Islam alone contains the final truth, as Muhammad was the Seal of Prophets. This answer, usually given by so-called fundamentalists, leaves most Western seekers and quite a number of Western-educated Muslims unsatisfied, simple and convincing as it is.

To be sure, nobody nowadays would agree with the poisonous remark written by an unsuccessful missionary to the Muslims and published in The Moslem World (12, 1922, p. 25):

Even if a savage found a full satisfaction in animism, or a semi-civilized man in Islam, that does not prove that either animism or Islam could meet the need of civilized man.

The extreme wealth of Islamic literatures, of works of art, of psychological insight as developed over the centuries in Sufism; the refined though (for an outsider's understanding) complicated network of legal and ritual prescriptions: all this is being discovered slowly in the West, and attempts to understand and interpret Islam, especially in its mystical dimensions, for modern Westerners are increasing, as is the number of converts in Europe and America.

Scholars and politicians used to ask whether Islam can be ‘reformed’, and whether it has to be reformed. During my years at the Ilâhiyat Fakültesi in Ankara, where we worked to introduce young Muslim theologians to the techniques of modern critical scholarship and European thought-systems to enlarge their horizons, one question surfaced time and again: is there no Luther available for Islam? Turkish students as well as modernist thinkers have often mentioned the example of Luther as a possible ‘saviour’ for present-day Muslims (while Iqbāl, well read in European history, saw him as a negative force responsible for the break-up of Christian Europe!). However, as Islam has no structure comparable to that of the Roman Catholic Church, and no centralized source of authority such as the Pope, it is next to impossible to imagine a single person emerging and ‘freeing’ Islam from what Fazlur Rahman has called ‘the dead weight of time’. Islam was at its beginning a reform movement which brought a fresh approach to life into the medieval world but became increasingly surrounded over the centuries by an ever-hardening crust of legalistic details, of traditions, scholia, commentaries and supercommentaries under which the original dynamic character of the revelation, the innovative impetus of the Prophet, seemed to disappear, so much so that Lord Cromer, more than a century ago, made the famous remark that ‘reformed Islam is no longer Islam’.2

But, like any other religion, Islam has been growing in a constant dialectic movement which, in contemporary parlance, would be called the interplay of Chaos and Order—the sunna was always ‘disquieted’ by the introduction of bid‘as, innovations. That was particularly true when Islam expanded to the furthest corners of Asia and Africa and, naturally enough, took over a more or less significant part of indigenous traditions. The ‘urf, custom, or ‘ādat law, according to the different countries gained its place besides the sharī‘a law. Normative Islam as laid down in the books of classical theologians and jurists and taught in the madrasas, the use of the ‘letters of the Koran’ and the sacred Arabic language, and the conscious following of the Prophet's example as expressed in the ḥadīth characterized the umma wherever Islam reached. All these factors helped to create a picture of a uniform, even ‘monolithic’ Islam; and yet a large variety of popular forms grew, especially due to Sufism with its emphasis, mainly on the folk level, on the veneration of saints. This trend often appeared to the normative believers as mere idol-worship, as a deviation from the clear order to strict monotheism which had to be defended against such encroachments of foreign elements, which, however, seemed to satisfy the spiritual needs of millions of people better than legal prescriptions and abstract scholastic formulas. But tawḥīd, strictest monotheism, is the quintessence of Islam along with the acknowledgment that this religion was established in its temporal manifestation by Muhammad—hence the tendency to go back, in cases of doubt, to the days of the Prophet, the ideal time, indeed the fullness of time, which was and should remain the model for the generations to come.3 Muhammad is the centre of history; his is the middle way between stem legalism as manifested through Moses and world-renouncing asceticism and loving mildness embodied in Jesus; he constitutes, as mystics would say, the means in which ghayb, the Invisible, and skahāda, the visible and tangible, meet, and is thus the Perfect Man tot’ exochén.

The shahāda in its two parts is the foundation of Islam, and a Muslim is a person who pronounces it and accepts the validity of the sharī‘a as the God-given path to walk on.

But there is the need for a deeper ethical dimension, īmān, ‘faith’, which has been expressed in very many writings, most notably (and the best-known of which are) those by al-Ghazzālī. The very definition of muslim and mu'min, or islām and īmān (cf. Sūra 49:14), shows that besides the formal acceptance of the religion of ‘surrender’ there has to be inner faith, and the introduction of the third term, iḥsān, ‘to do good’, or, as a Sufi master in Hyderabad/Deccan explained to us, ‘to do everything as beautifully as possible’ because God watches over each and every human act, brings a deep personal piety to the fore. Everything should be done in absolute sincerity, ikhlāṣ, without any admixture of selfishness or ‘showing off’. Then, even the simplest action will bear good fruits. This attitude seems to be expressed in the Prophet's answer to the question: ‘What is virtue?’, to which he replied: ‘Virtue is that in which the heart becomes peaceful’. Not so much an external legal decision, fatwā, is the thing that matters, but: ‘Ask your heart for fatwā’ (AM no. 597).

The fact that Muslim thinkers always want to go back to the Prophet's time has led many observers to believe that Islam became fossilized as a result of the strict clinging to externals. Yet, modernists have constantly drawn their coreligionists’ attention to the Koranic statement: ‘Verily, God does not change a people's condition unless they change what is in them’ (Sūra 13:12), for, as has been seen (above, p. 220), predestination, which looms large in the Koran and even more in ḥadīth, is only one of the two ways of giving a meaning to one's life. The belief in a predestined order in the universe is, in its deepest meaning, the human attempt to take God seriously as the only acting power and to surrender completely to Him and His wisdom. However, the Muslims were also very much aware that the acceptance of a kind of mechanical working of Fate can lead to laziness and is often used as an excuse for one's own faults instead of ascribing one's good actions to God and blaming oneself for one's faults and sins. After all, the Koran (Sūra 479) states clearly: ‘Whatever of good befalls you is from God, and whatever of evil befalls you, it is from yourself’. The ḥadīth: qad jaffa ‘l-qalam, ‘The Pen has dried up’ (AM no. 92), should therefore not be interpreted as meaning that everything and every human act was written once for all time but rather, as Rūmī insists, that there is one absolutely unchanging law, that is, good actions will be rewarded while evil will be punished.

To be sure, there was always an unsolved aporia between the belief in predestination and that in free will, but the ḥadīth according to which ‘this world is the seedbed of the Hereafter’ (AM no. 338) was meant to spur the believers to good actions as did the Koranic emphasis on doing good, for Divine Justice will place even the smallest act on the balance (cf. Sūra 99).

For some thinkers, the problem of free will and predestination meant that the human being will be judged according to his or her capacity:

One does not beat an ox because he does not sprout wings,

but beats him because he refuses to carry the yoke…

(M V 3, 102)

Predestination could thus be explained as the development of one's innate talents: one cannot change them but can work to develop them as beautifully as possible until the nafs, which once was ‘inciting to evil’ (Sūra 12:53), is finally tamed and, strengthened by its steady struggle against adversities and temptations, reaches inner peace so that it can return to its Lord (Sūra 89:27–8).

Nevertheless, there has always been a certain emphasis on those ḥadīth that defend absolute predestination, culminating in the oft-repeated ḥadīth qudsī: ‘Those to Paradise, and I do not care, and those to Hell, and I do not care’ (AM no. 519).

God appears in poetical parlance as the Master Calligrapher who writes man's fate ‘on his forehead’ (sarnivisht in Persian, alĭn yazĭsĭ in Turkish), or else He appears as the great Weaver or the Playmaster whose hands hold the strings of the puppets in the great theatre of the world and move them according to His design to cast them, in the end, again into the ‘dark box of unity’. And there were and still are outcries against the seemingly ‘unjust’ acts of God, whether in ‘Aṭṭār's dramatic prayers or in more flippant style in ‘Omar Khayyām's rubā‘īyāt and, half-jokingly, in Turkish Bektashi poetry. Perhaps the finest definition of free will is that by Rūmī:

Free will is the endeavour to thank God for His beneficence (M I 929).

For gratitude—often contrasted with kufr, ‘ingratitude, infidelity’—is a quality highlighted in the Koran (cf. Sūra 42:43). True gratitude, which draws more and more graces upon the believer, is manifested in the loving acceptance of whatever God sends. By gratefully accepting one's ‘fate’, the human may reach, ideally, uniformity with God's will and thus realize what modernists have called jabr maḥmūd, a ‘higher predestinarianism’ in loving surrender to whatever God has decreed.

This kind of lofty thought is, understandably, not as common as it ideally should be. Modern times have brought such a shift in the religious consciousness not only of Muslims but also everywhere else that it is small wonder when in much of modem literature in the different languages of the Muslim world Islam, either in its official or in its popular form, appears as the attitude of old-fashioned, middle-class or simple people (a kind of attitude formerly called, often condescendingly, ‘the faith of the old women of the community’).4 The excesses of ‘saint-worship’ are banded just as much as ‘molla-ism’, the attitude of the hardline religious orthodoxy, of lawyer-divines or religious teachers, whose behaviour is often incompatible with the ideals that they preach. In poetry, one may find, at least for a moment, a return to figures of the mystical tradition such as al-Ḥallāj who, however, are interpreted as representatives of a free, loving religiosity and are posited against narrow orthodoxy or, even more, depicted as rebels against the ‘establishment’ or a government considered to be a traitor to the ideals of true Islam.5 An additional problem is that the majority of modern, educated Muslims are used to thinking in either English or French and have to find a new language to express their ideas which, again, are largely coloured by their acquaintance with Western literary models rather than with classical Islamic ones. For many Muslims are now born in a completely un-Islamic environment, and often come from a background that has nothing in common with the traditional Islamic settings. The various strands of Muslims—either born Muslims or converts—in the USA, the Indians and Pakistanis in the UK, the Turks in Germany and the Algerians in France offer the most divergent approaches to what seems to them ‘true Islam’ as well as to the problem of the umma; and recent Western converts again add new shades of understanding to the picture, shades that alternate between theosophical mysticism and strictest observant, normative Islam.6 They no longer read and write in the classical languages of the Islamic world, and when their brethren and sisters in the Middle East do, they perhaps try to couch their message in an antiquated Arabic style, or else shape their native tongues (Persian, Urdu, even more Turkish) to cope with the exigencies of our time.

For the influence of European languages in both vocabulary and syntax, let alone thought patterns, on the ‘Islamic’ languages creates a literary idiom quite different from the classical one, so that many of the precious and meaningful images or expressions of previous times are irretrievably lost. Alternatively, allusions to and terms from the religious traditions are used in such a skilful way that the non-Muslim reader barely recognizes the ‘blasphemous’ meaning that a seemingly harmless sentence or image may contain.

But usually, the younger generation both of Western-educated Muslims in the East and those who have grown up in the West know precious little of their own tradition; everyone who has taught classical literature in Arabic, Turkish, Persian or Urdu to native speakers of these languages experiences this break with the tradition. And it is understandable that ‘fundamentalism’, with its return to and stem observance of time-honoured models, emerges as a reaction to such overly Westernizing trends.

Westernization goes together with a diminishing knowledge of the sacred language, Arabic, but also with attempts to de-Arabicize the Islamic world. A tendency expressed decades ago by Turkish reformers such as Zia Gökalp is typical of such movements, whose fruits are seen, for example, in the secularization of Turkey (where, however, a strong feeling for Islamic values continues beneath the Westernized surface). Similar approaches can also be found in India in the work of scholars like A. A. A. Fyzee, while Iqbāl advocated a return to the central sanctuary, to Mecca, which should go together with a revival of the original, dynamic and progressive Islam. And what will be the post-modernist perceptions of Islam of which the brilliant Pakistani anthropologist Akbar S. Ahmad speaks?7

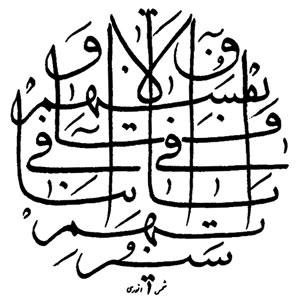

Nathan Söderblom once defined the use of the negation in the ‘prophetic’ and the ‘mystical’ type of religion: the ‘prophetic No’ is exclusive, as is the lā ilāha illā ‘Llāh in the shahāda: ‘No deity save God’; and whatever is against this absolute truth is dangerous, prohibited, sinful and, as the Muslim would say, has to be cut off ‘with the sword of lā’ (which in its graphic form somewhat resembles a two-edged sword). The ‘mystical No’, on the other hand, is inclusive, and that is expressed in the transformation of the shahāda into the words, lā maujūda illā Allāh, ‘there is nothing existent but God’, who includes everything.

This twofold orientation of Islam towards the ẓāhir and the bāṭin the exoteric ‘prophetic’ and the esoteric ‘mystical’ stance, has continued down through the centuries. It is clearly visible in Indian Islam, for example where one finds the ‘Mecca-oriented’ normative piety of the theologians who still felt ‘in exile’ in the subcontinent although their families had lived in India for hundreds of years, while the ‘India-oriented’ current emphasized the compatibility of Islam with the indigenous traditions and achieved amazing synthetic results, for example in mystical folk poetry.

It is also possible to see the inner-Islamic tensions expressed in terms of ‘nomos-oriented’ and ‘eros-oriented’ religion: normative Islam is, no doubt, nomos-oriented, built upon the Law in which God's will is revealed, and therefore averse to movements and people that seem to break out of the sacred limits of the Law to indulge in practices not exactly compatible with the norms. That is especially the case in a large part of Sufism, which expressed itself in poetry, music and even dance with an emphasis on feeling and ‘tasting’—in short, in ecstatic movements which are typical of the eros-oriented (in the widest sense of the term) attitude. ‘Sober’ Sufis often tried to strike a balance between both aspects and to show that they were inseparably intertwined and that every unusual spiritual progress or event had to be weighed against the balance of the Law. For sharī ‘a, ‘Law’, and ḥaqīqa, ‘Divine Truth’, belong together just as the shahāda in its first part points to the Divine Reality and in its second part to the Law. Similarly, according to Qushayrī's remark, the sentence in the Fātiḥa, iyyāka na‘budu, ‘Thee we worship’, points to the Law, while its continuation, iyyāka nasta‘īn, ‘To Thee we turn for help’, refers to the Divine Reality.8

The Law promises, perhaps even guarantees, the human being's posthumous salvation, while in the mystical trends the tendency is to ‘touch’ the Divine here and now, to reach not so much a blessed life in the Hereafter (which is only a kind of continuation of the present state) but rather the immediate experience of Love. The Sufis’ ecstatic experiences and at times unbridled utterances could lead to death (both mystical death and execution by the government), while normative theology shows the way to perfect happiness during one's life by dutifully following the right path and obeying God's laws. The poets expressed this contrast by speaking of ‘gallows and minbar’: the mystical lover will die for his love; the sober preacher will call people to obedience from the minbar, the pulpit; and yet gallows and pulpit are made from the same wood.9

When William James claims that ‘sobriety says No while drunkenness says Yes’, this statement is very applicable to the ‘prophetic’ and the ‘mystical’, the exclusive and the inclusive No in Islam or, as we saw earlier (see above, p. 191), to the juxtaposition of qurb al-farā'iḍ, the proximity reached by the punctual fulfilment of ritual duties, which is the prophets’ way, and qurb an-nawāfil, the proximity reached by supererogative works, which is the way of God's friends, the awliyā.

Again, while the Prophet said: ‘We do not know Thee as it behoves!’, the Sufi Bāyezīd Bisṭāmī called out: ‘Subḥanī’, ‘Praise to me!’ If we are to believe legend, it was the contrast between these two utterances that awakened Mawlānā Rūmī to the spiritual life. Rūmī, so it is told, fainted when listening to Shams's shocking question about whether Bāyezīd or the Prophet was greater, a question based on the two men's respective sayings that express the human reactions to the meeting with the Divine. The tensions between the two poles of religious experience, that of the prophet, who knows his role as humble ‘servant’, and that of the mystic, who loses himself in loving union, became clear to him.

There are, however, many different reactions of Muslims to the experience of the Numinous besides these two basic forms. There is unending awe, an awe like the one felt when one approaches the mighty Lord, the King of all kings—such an awe is an attitude expressed best in prayer and reflected in prayer poems.

Awe before the mysterium tremendum is natural, but one has also to reckon with fear—fear of the terrible Day of Judgment; fear when thinking of God's Justice with which one will be confronted on that day; fear of His ‘ruses’, the sudden changes by which He confuses those who are all-too-secure on the way and then meet with unexpected hardships; and if a wanderer may be too advanced to fear God's ruses, one may still fear being deprived of God's presence, of the consoling feeling mat He is watching here and now and that He is eternal when everything else will perish; and the mystic who has ‘found’ the Divine beloved may fear being separated from Him, a thought more terrible than Hellfire.

But there is also hope, the hope of the merciful God's endless capacity for forgiving one's sins and mistakes. Fear and hope, as the traditional saying claims, are ‘the two wings by which the soul flies towards God’, for too much fear stifles and paralyzes the soul, and too much hope can make humans frivolous and oblivious to their duties. Yet, hope always has the upper hand, as is understood from the ḥadith qudsī that one should ‘think well of God’ (see above, p. 223).

On a different level, fear and hope are expressed in the stages of qabḍ and basṭ, depression and elation; that is, the anguish of the soul, which feels like ‘living in a needle's eye’, when nothing is left but hope against all hope, and the elation during which the jubilant soul seems to encompass the entire universe, sees the world in radiant colours and sings of divine joy. These stages alternate in the course of one's life. The impression which the reader obtains is that the state of basṭ seems to dominate in mystical circles—how else is one to explain the thousands of ecstatic verses that translate the happiness of the lover who feels united with all and everything? Yet, the state of qabḍ, depression, is considered more valuable in the ‘sober’ traditions, for, while living through the dark night of the soul, one has to realize that there is only God to whom one can turn, and thus the ideal of pure worship of the One can be achieved better.

As important as awe, fear and hope are, in Islam the encounter with God will nevertheless be most frequently called ‘faith’. Unquestioning faith in His power and wisdom requires the belief in the positive meaning of everything He decrees in His eternal wisdom, negative as it may seem. For people sometimes hate something, and yet they will discover its positive aspects later on (cf. Sūra 2:216). Such faith can be considered the most characteristic quality of the true believer. So also is tawakkul, absolute ‘trust in God’. Tawakkul was developed into a multi-layered science of its own among the early Sufis, but could not be maintained in its pure form, for that would have formed a complete impediment to any practical work, not to mention to the believer's duties and responsibilities towards society. But, as an ideal, it remained a factor that largely coloured the Muslim's life.10

Love is certainly not an attitude which one expects to find on the general map of Islam, and the use of the term and the concept of love of God, or reciprocal love between God and humans, was sharply objected to by the normative theologians: love could only be love of God's commands, that is, strict obedience. Yet, it remained the central issue with the mystically-minded, whose love was directed first exclusively to God (one of whose names is al-wadūd, ‘the Loving’, in Sūra 11:90; 85:14) but then turned more and more to God's beloved, ḥabīb, namely the Prophet, love for whom became a highly important ingredient in Muslim life. And in many ecstatic love poems written in the Islamic, particularly the Persianate, world, one can barely discern whether the beloved object addressed is God, the Prophet, or a human being in whom the poet sees Divine beauty manifested.

Love engenders gratitude and peace of mind: the concept of iṭmi'nān, the resting peacefully in God's will, plays a distinctive role in the Koran. ‘Is it not that the hearts find peace by remembering God?’ (Sūra 13:28). It is this peace and stillness reached through constant recollection of God which characterizes the soul's final stage. The concept of this peace and stillness, which is a sign of yaqīn, the ‘absolute certainty’, has been combined with the legend of the opening of Muhammad's breast when he experienced a soothing coolness and quietude. One finds a beautiful interpretation of his event and the ensuing peaceful serenity in an unexpected source, namely in a sentence of the German author Jean Paul (d. 1825), who writes:

Als Gott (nach der Fabel) die Hände auf Muhammad legte, wurd’ ihm eiskalt; wenn ein unendlicher Genuß die Seele mit dem höchsten Enthusiasmus anrührt and begabt, dann wird sie still und kalt, denn nun ist sie auf ewig gewiß.

When God, according to the legend, placed His hands upon Muhammad, he turned as cold as ice; when an infinite pleasure touches the soul and inspires her with the highest enthusiasm, she becomes quiet and cold, for now she is certain in eternity.

This quiet, cool certainty of having reached the goal seems perhaps to contrast with the fiery, restless seeking and the never-resting striving on the path, and yet it is often mentioned by deeply religious people.

Similarly, observers have often emphasized the Muslim's seriousness in demeanour and general attitude, a seriousness typical of nomos-oriented religions; yet the inner joy does not lack either; the Sufi Abū Sa‘īd-i Abū' l-Khayr is probably the most radiant example of the joy which, as Fritz Meier has lucidly shown, is an integral part of true Sufi life.11

Out of such an inner joy grows the praise and laud of God which permeates the whole universe. As the first Sūra of the Koran begins with the words al-ḥamdu lillāh, ‘Praise be to God’, thus praise of God Jills the created world, audible to those who understand the signs. Is not Muhammad's very name derived from the root ḥ-m-d, ‘to praise’? Thus he will carry the ‘banner of praise’ in the field of Resurrection when those who constantly praise the Lord will be, as popular tradition has it, the first to enter Paradise.12

Gerardus van der Leeuw has offered different typologies of religion, and one may wonder which one may be most suitable for Islam. When it comes to the human attitude to God, one would certainly say that Islam is the ‘religion of servitude’ to God: the term ‘abd, ‘slave’, for the human being points to this truth, as does the idea that ‘abduhu, ‘God's servant’, is the highest rank that a human being can reach (see above, p. 179). This servitude, in which all of creation is united, is best expressed in the prostration in ritual prayer.

One can also speak of a ‘religion of the Covenant’, though it is not as outspoken as in Judaism, where the Covenant is the true heart of religion (a fact mentioned several times in the Koran). Yet, the Primordial Covenant (Sūra 7:172) is the metahistorical foundation of the relation between God and humankind: they have promised to acknowledge Him as the Lord and King at the time before times, and thus are bound to obey Him to the Day of Judgment—again as His servants.13

Another concept is that of ‘friendship with God’, connected in particular with Abraham, who is called khalīl Allāh, ‘God's friend’. But such friendship and close bond of relation is much more important in the use of the term walī (plural awliyā'). This word, which occurs often in the Koran, points to the relation between the Divine Lord and His friends, or perhaps better ‘protégés’, who are under His protection and ‘have neither fear nor are they sad’ (Sūra 10:62). The whole development of the hierarchy of the awliyā', the ‘friends of God’ in Sufism, belongs to this sphere. Furthermore, the Shia term for ‘Alī, walī Allāh, singles out the Prophet's cousin and son-in-law as the one who was especially honoured by God's protective friendship which He shows to those whom He elects.

G. van der Leeuw speaks of the ‘religion of unrest’ when discussing ancient Israel, but this term can be applied as well to Islam, for God is never-resting Will: ‘neither slumber nor sleep seize Him’ (Sūra 2:255), and ‘He is constantly in some work’ (Sūra 55:29).

The concept of a ‘religion of unrest’, often forgotten in times when scholastic definitions seemed to overshadow and even conceal the picture of the living and acting God of the Koranic revelation, has been revived in the twentieth century by Iqbāl, who never tired of emphasizing that Islam is a dynamic force and that it is the Living God of the Koran whom the Muslims should remember and to whom they should turn instead of indulging in Hellenizing mystico-philosophical ideas of a mere prima causa which has receded completely from active involvement in the world. Indeed, many orientalists and religious historians, especially during the nineteenth century, have regarded Islam as a purely deistic religion. But many mystics had stressed the living and never-resting activity of God: the story that Rūmī tells both in his Dīvān (D no. 1, 288) and in Fīhi mā fīhi (ch. 27) is a good example of this point. One winter day, a poor schoolmaster saw a bear (apparently dead) drifting down a river in spate and, incited by the school-children to grab this wonderful fur coat, jumped into the water but was grasped by the bear. Called back by the frightened children, he answered: ‘I'd love to let the fur coat go, but it does not let me go!’ Thus, Rūmī concludes, is God's mercy, love and power, which do not leave the poor human beings but follow them untiringly to draw them near. Already, three centuries earlier, the Iraqi mystic Niffarī (d. 965) had symbolized God's never-resting will to save His creatures in a parable that was rightly compared to Francis Thompson's Hound of Heaven.14

For God's power shows itself in His will, and He wills that humanity be saved; once humans understand that, then faith, obedience and gratitude issue naturally from this knowledge.

It is the concept of will and obedience which, in van der Leeuw's scheme, is typical of ancient Israel's religious stance. But again, the model fits Islam perfectly. Where in the Old Testament failures and mishaps are ascribed to the people's lack of obedience, the same is true in Islam. The Koran (Sūra 3:152) blames the Muslim defeat in the battle of Uhud (625) upon the hypocrites and the disobedient Muslims: misfortune is a punishment for disobedience. Two of the most eloquent modern expressions of this feeling are Iqbāl's Urdu poems Shikwa and Jawāb-i Shikwa, ‘Complaint’ and ‘God's answer to the complaint’ (written in 1911–12), in which the Muslims, lamenting their miserable situation in the modern world, are taught by God's voice that it is their own fault: they have given up obedience and neglected their ritual duties, so how can they expect God to guide them after straying off the straight path? Did not the Koran often mention the fate of ancient peoples who disobeyed God and His messengers? Thus, in every historical catastrophe, the Muslim should discover an ‘ibra, a warning example for those who believe and understand.

According to van der Leeuw's model, Islam is the ‘religion of Majesty and Humility’—a beautiful formulation which certainly hits the mark, as the whole chapter on Islam reveals his insight into Islam's salient features. Surrender, islām, to the Majesty beyond all majesties is required, and Temple Gairdner, as cited by van der Leeuw, despite his otherwise very critical remarks about Islam, speaks of ‘the worship of unconditioned Might’. Islam, according to another Christian theologian quoted by van der Leeuw, ‘takes God's sovereignty absolutely seriously’, and Muslims believe in God's power and might without any suspicion or doubt. Lately, J. C. Bürgel has tried to show how Islamic culture develops out of the tension between God's omnipotence and the unceasing human attempt to create a power sphere of one's own.15 It is the attitude of unquestioning faith which, as van der Leeuw says, makes Islam ‘the actual religion of God’. And it may well be that this feeling of God's absolute omnipotence, which is the basis of Muslim faith at its best (and which is slightly criticized by van der Leeuw), shocks and even frightens human beings in a time of increasing distance from ‘God’, of secularization, of loss of the centre.

The historian of religion would probably be surprised to see that Muslims have also called Islam the ‘religion of Love’, for Muhammad, so they claim, appropriated the station of perfect Love beyond any other prophet, since God took him as His beloved—Muḥammad ḥabībī. Therefore, Muhammad is regarded as the one who shows God's love and His will and thus guides humanity on the straight path towards salvation, as the Koran states: ‘Say: If you love God then follow me, so that God loves you’ (Sūra 3:31). He brought the inlibrated Divine Word in the Koran, and he preached the absolute unity of God around which theology, philosophy and mystical thought were to develop.

One can well understand that the words of the two-part shahāda are the strong fortress in which the believer finds refuge; but nothing can be predicated upon God Himself: ‘He was and is still as He was’.

For the pious Muslim, islām shows itself everywhere in the universe—in the blood circulation, the movement of the stars in their orbits, in the growth of plants—everything is bound by islām, surrender and subordination to the Divinely-revealed Law. But this islām—as at least Mawlānā Mawdūdī holds—then became finalized in historical Islam as preached by Muhammad.16 The differentiation which is made in Urdu between muslim, someone or something that practises surrender and order by necessity, and musulmān, the person who officially confesses Islam, is typical of this understanding. And this differentiation also underlies Goethe's famous verse in the West—Östlicher Divan:

Wenn Islam Ergebung in Gottes Willen heißt—

In Islam leben und sterben wir alle.

(If Islam means surrender to God's will, then all of us live and die in Islam).

Historians have compared the Divine voice that was heard in Mecca to that of a lion roaring in the desert, and have often seen Islam as a typical religion of the desert, overlooking the fact that Islam was preached first and developed later in cities: in the beginning in the mercantile city of Mecca, later in the capitals of the expanding empire. ‘City’ is always connected with order, organization and intellectual pursuits, while the desert is the dangerous land where spirits roam freely and where those possessed by the madness of unconditioned love may prefer to dwell; those who do not follow the straight path between two wells will perish there.

It is the city that offers us a likeness of Islam, which can be symbolized as a house, based on the Koranic expression dār al-Islām.17 It looks indeed like a house, a strong Oriental house, built of hard, well-chiselled stones and firmly resting on the foundation of the profession of faith and supported by four strong pillars (prayer, alms tax, fasting and pilgrimage). We may observe guards at its gate to keep away intruders and enemies, or see workmen with hammers and swords to enlarge parts of the building lest the shifting sand-dunes of the desert endanger it. We admire the fine masonry but find it at first glance rather simple and unsophisticated. But when entering the large building, we see lovely gardens inside, reminiscent of Paradise, where watercourses and fountains refresh the weary wayfarer. There is the ḥarīm, the women's sacred quarters, where no stranger may enter because it is the sanctuary of love and union.

The house is laid out with precious carpets and filled with fragrance. Many different people bring goods from the seven climates and discuss the values of their gifts, and the Master of the house admonishes everyone to keep the house clean, for after crossing its threshold and leaving one's sandals outside, one has entered sacred space.

But where is one to find the builder and owner of the house? His work and His orders give witness to His presence, awesome and fascinating at the same time, but human reason cannot reach Him, however much it exerts itself and tries to understand in which way He will protect the inhabitants of the House of Islam, of the house of humanity.

Perhaps Rūmī can answer the human mind's never-ending question as to how to reach Him who is the Merciful and the Powerful, the Inward and the Outward, the First and the Last, the One who shows Himself through signs but can never be comprehended:18

Reason is that which always, day and night, is restless and without peace, thinking and worrying and trying to comprehend God even though God is incomprehensible and beyond our understanding. Reason is like a moth, and the Beloved is like the candle. Whenever the moth casts itself into the candle, it burns and is destroyed—yet the true moth is such that it could not do without the light of the candle, as much as it may suffer from the pain of immolation and burning. If there were any animal like the moth that could do without the light of the candle and would not cast itself into this light, it would not be a real moth, and if the moth should cast itself into the candle's light and the candle did not burn it, that would not be a true candle.

Therefore the human being who can live without God and does not undertake any effort is not a real human being; but if one could comprehend God, then that would not be God. That is the true human being: the one who never rests from striving and who wanders without rest and without end around the light of God's beauty and majesty. And God is the One who immolates the seeker and annihilates him, and no reason can comprehend Him.

- 1.

The number of works about different aspects of modem Islam increases almost daily. Some useful studies are: John J. Donohue and John L. Esposito (eds) (1982), Islam in Transition: Muslim Perspectives; Gustave E. von Grunebaum (1962), Modem Islam. The Search for Cultural Identity; Werner Ende and Udo Steinbach (eds) (1984), Der Islam in der Gegenwart, Wilfred Cantwell Smith (1957), Islam in Modern History; idem (1947): Modem Islam in India (2nd ed.); and Rotraut Wielandt (1971), Offenbarung und Geschichte im Denken moderner Muslime.

- 2.

C. H. Becker (1910), ‘Der Islam als Problem’; Johann Fück (1981a), ‘Islam as a historical problem in European historiography since 1800’. About different ways of dealing with Muhammad in earlier times, see Hans Haas (1916), Das Bild Muhammads im Wandel der Zeiten.

- 3.

Johann Fück (1981b) ‘Die Rolle des Traditionalismus im Islam’; Sheila McDonough (1980), The Authority of the Past. A Study of Three Muslim Modernists; Richard Gramlich (1974b), ‘Vom islamischen Glauben an die “gute alte Zeit”’.

- 4.

See, for example, M. M. Badawi (1971), ‘Islam in modem Egyptian literature’.

- 5.

Thus Ṣalāḥ ‘Abd aṣ-Ṣabūr (1964), Ma'sāt al-Ḥallāj; English translation by K. J. Semaan (1972), Murder in Baghdad. See also A. Schimmel (1984b), ‘Das Ḥallāğ-Motiv in der modernen islamischen Dichtung’.

- 6.

About modern movements and problems in America, see Earle Waugh, Baha Abu-Laban and Regula B. Quraishi (eds) (1983), The Muslim Community in North America; Khalid Duran (1990), ‘Der Islam in der Mehrheit und in der Minderheit’; idem (1991), ‘“Eines Tages wird die Sonne im Westen aufgehen”. Auch in den USA gewinnt der Islam an Boden’.

- 7.

Akbar S. Ahmad (1992), Postmodernism and Islam. Predicament and Promise.

- 8.

Qushayrī (1912), Ar-risāla, p. 261; the same idea in Hujwīrī (1911), Kashf al-mahjūb, p. 139.

- 9.

The expression is used in Nāṣir-i Khusraw (1929), Dīvān, p. 161; also in idem, tr. A. Schimmel (1993), Make a Shield from Wisdom, p. 78.

- 10.

See B. Reinert (1968), Die Lehre vom tawakkul in der klassischen Sufik.

- 11.

F. Meier (1976), Abū Sa‘īd-i Abū'l Hair. Leben und Legende.

- 12.

The glorification of God which, according to the Koran, permeates the universe had led early Muslims to the idea that ‘a fish or a bird can only become the victim of a hunter if it forgets to glorify God’ (Abu'l-Dardā, d. 3211/652). See S. A. Bonebakker (1992), ‘Nihil obstat in storytelling?’ p. 8.

- 13.

R. Gramlich (1983a), ‘Der Urvertrag in der Koranauslegung’.

- 14.

Niffarī (1935), Mawāqif wa Mukhāṭabāt, ed. and transl. by A. J. Arberry, Mawqif 11/16.

- 15.

J. C. Bürgel (1991), Allmachl und Mächagkeit, passim.

- 16.

Mawlānā Mawdūdī's views, often published in Urdu and translated into English, are summed up in Khurshid Ahmad and Z. I, Ansari (eds) (1979), Islamic Perspectives. In this volume, the article by S. H. Nasr, ‘Decadence, deviation and renaissance in the context of contemporary Islam’, pp. 35–42, is of particular interest. See further Muhammad Nejatullah Siddiqi's contribution, ‘Tawḥīd, the concept and the prospects’, pp. 17–33, in which the author tries to derive the necessity of technology for communication, organization and management in the religious and worldly areas from the central role of tawḥīd. An insightful study of the problems is Fazlur Rahman (1979), ‘Islam: challenges and opportunities’.

- 17.

For the ‘House’, see Juan E. Campo (1991), The Other Side of Paradise, and A. Petruccioli (1985), Dār al-Islam. Titus Burckhardt has attempted to show the truly ‘Islamic’ city in his beautiful book (1992) on Fes, City of Islam.

- 18.

Fīhi mā fīhi, end of ch. 10.