And of His signs is that He created you from dust, and you became humans, all spread around.

Sūra 30:20

‘To reflect on the essence of the Creator… is forbidden to the human intellect because of the severance of all relations between the two existences.’ Thus wrote Muhammad ‘Abduh, the Egyptian modernist theologian.2 Islam has generally held the opinion that it is sinful to apply human reason to God. The ḥadīth states: ‘Think about the creation, but do not think about the Creator’ (AM no. 439). One has to accept the way in which He describes Himself in the Koran, for according to Ismā‘īl Rājī al-Fārūqī, ‘The Qur'an expresses God's inconceptualizability in the most emphatic manner’.3

Ancient religions had tried to circumscribe the Numinous power in various ways. The High God was recognized as causing and maintaining creation, and could be symbolized as father or, less frequently in historic times, as mother. Functional deities were in many religions responsible for the different events in Nature and in life: in the high religions many of them were ‘sublimated’, as it were, into saints who are thought to perform similar functions—hence the aversion of traditional Muslims to saint-worship, which, as they feel, imperils the pure, true monotheism whose confession is the duty of the believers.

Religions of antiquity also saw Fate as an impersonal power behind the events, and ancient Arabic as well a good part of Persian poetry reflects that fear of the revolving sky which, like a millstone, crushes everything. Who can escape the movement of the haft āsiyā, the ‘seven mills’, as the spheres are sometimes called in Persian? Who is not trampled down by the black and white horses which draw the chariot of the sky? Who knows what cruel Time has in its store, on its loom? The feeling that a merciless Fate reigns over the world surfaces time and again in literature,4 and yet there is a deep difference between this fatalism, which the Oriental world inherited from earlier systems of thought, and the belief in the active God who cares for His creatures and who knows best what is good in any moment of life even though His wisdom is often incomprehensible to human minds and one wonders what He intends. To be sure, there are enough statements, especially in the ḥadīth, in which God's omnipotence seems to be expressed through a seemingly feelingless fate, such as the famous ḥadīth qudsī;: ‘Those to Paradise and I do not care, and those to Hell and I do not care’ (AM no. 519). Predestination of this kind seems illogical, even downright cruel, to a modern mind, but it expresses a strange, irrational relation between the human ‘slave’ and the Lord; a relation which Tor Andrae, the Swedish Islamicist and Lutheran bishop has described thus: ‘Belief in predestination is the deepest and most logical expression of interpreting the world and human life in a purely religious way’.5 This statement translates well the Muslim's understanding of God's omnipotence and absolute Lordly power.

History of religions knows of different ways to describe God or, at least, to try to understand Him. There are the via causaliatis, the via eminentiae and the via negationis. All three can be comfortably applied to Islam, although the first one seems to be predominant in the Koranic message. Among His names, al-khāliq, al-bārī, al-muṣawwir, ‘the Creator, the Shaper, the Form-giver’ stand besides others that point to His care for His creatures, such as ar-rāziq, ‘the Nourisher’. He is al-muhuī al-mumīt, the One ‘who gives life and who gives death’. ‘Every day He is in some work’ (Sūra 55:29), that is, He never rests, and ‘slumber or sleep do not touch Him’ (Sūra 2:255). Just as He has placed His signs ‘in the horizons and in themselves’ (Sūra 41:53), He also ‘taught Adam the names’ (Sūra 2:31), and furthermore ‘He taught the Koran’ (Sūra 55:2). That means that He taught everything, for the Koran contains the expression of His will, while the names endow humankind with the power over everything created as well as with an understanding of the Divine Names through which His creative power manifests itself.

One could transform the words of the shahāda that ‘there is no deity save Him’ into the statement that there is no acting Power but Him, for all activities begin from Him: He began the dialogue with humanity in pre-eternity by asking in the Primordial Covenant alastu bi-rabbikum, ‘Am I not your Lord?’ (Sūra 7:172), and He inspires prayer and leads people on the right path if He so wishes. Yet the supreme cause of everything perceptible is not perceptible Itself.

As much as tradition and the Koran use the via causalitatis to point to God's power, they also use the via eminentiae, that is, they show that He is greater than everything conceivable. This is summed up in the formula Allāhu akbar, ‘He is greater (than anything else)’; and He is ‘above what they associate with Him’ (Sūra 59:23).

But His is also the absolute Beauty, even though this is not stated explicitly in the Koran. Yet, the ḥadīth ‘Verily God is beautiful and loves beauty’ (AM no. 106) was widely accepted, especially by the mystically-minded, and when daring Sufis claimed that the Prophet had said: ‘I saw my Lord in the most beautiful form’, they express the feeling that longing for this Absolute Beauty is part of human life.

God is absolute Wisdom, and the Muslim knows that there is a wisdom in everything. For ‘God knows better (than anyone)’, Allāhu a‘lam, as is repeated in every doubtful case. Therefore, God should not be asked why this or that happened, and ‘Alī's word: ‘I recognized my Lord through the annulment of my intentions’ (AM no. 133) reflects this mentality: the Lord's strong hand should be seen even in moments of disappointment and despair, for, as the Koran states (Sūra 21:23), ‘He is not asked about what He does’. This feeling has inspired Rūmī's poetical version of Adam's prayer in the Mathnawī (M I 3, 899ff.):

If You treat ill Your slaves,

if You reproach them, Lord—

You are the King—it does

not matter what You do.

And if You call the sun,

the lovely moon but ‘scum’,

And if You say that ‘crooked’

is yonder cypress slim,

And if You call the Throne

and all the spheres but ‘low’

And if You call the sea

and gold mines ‘needy, poor’—

That is permissible,

for You're the Perfect One:

You are the One who can

perfect the transient!

God's will is higher than any human will, but this description does not mean, as Fazlur Rahman says, that we have to do with a ‘watching, frowning and punishing God nor a chief Judge, but a unitary and purposive will creative of order in the universe’.6 Thus, the constant use of mā shā' Allāh, ‘what God wills’ or, even more, inshā Allāh, ‘if God wills’, does not refer to any whim of the Lord but rather to His limitless power.

God is the One who dispenses absolute Justice, so much so that one of the most penetrating books on Islamic theology is called ‘God of Justice’.7 However, overemphasis on His justice, ‘adl, as was practised by the Mu‘tazilites, could conflict with His omnipotence, because His justice was judged according to human understanding of ‘justice’, which is not applicable to God. The description of God as the khayr al-mākirīn, ‘the best of those who use ruses’ (Sūra 3:54, 8:30), and the entire problem of His makr, ‘ruse’, belongs to the realm of His omnipotence; it cannot be solved by human reasoning.8

God is the absolute Truth, al-ḥaqq. It is therefore not surprising that the term ḥaqq was later used by the Sufis to point to the innermost essence of God, who was experienced as the sole Reality, something beyond all definitions—and before the ḥaqq, all that is bāṭil, ‘vain’, disappears (Sūra 17:81).

God is higher than everything—not only in His will, justice or knowledge, but He is also supreme mercy and love, even though the quality of love is rarely if ever mentioned in the Koran (cf. Sūra 5:59, end) but is reflected in His name, al-wadūd (Sūra 11:90). Yet, mercy and compassion are expressed in His two names which precede every Sūra of the Koran, namely ar-raḥmān ar-raḥīm, ‘the All-Merciful the All-Compassionate’. They come from the root r-ḥ-m, which also designates the mother's womb, and thus convey the warm, loving care of the Creator for His creatures. These words, repeated whenever the Muslim begins something with the basmala, ‘inspired to the Muslim a moderate optimism’,9 and Islamic scholars have spoken, in the same context, of God's ‘providential mercy balanced by justice’. Later traditions emphasize that God acts in the way that human beings think He would—‘I am with My servant's thought’, says the ḥadīth qudsī, to point out that the one who trusts in God's forgiveness will not be disappointed.10 Rūmī tells the story of Jesus and John the Baptist; while the latter was constantly brooding in fear and awe, Jesus used to smile because he never forgot God's loving care and kindness, and therefore he was dearer to God.11

The via eminentiae can be summed up in the statement that, as God's perfections are infinite, ‘there is no perfection compared to which there is not a still greater perfection in God and with God’, and rightly did an oft-quoted Arabic verse say:

Praised be He by whose work the intellects become confused;

praised be He by whose power the heroes are incapacitated!

This exclamation of utter confusion leads to the third way of describing God, the via negationis:

Whatever you can think is perishable—

that which enters not into any thought, that is God,

says Rūmī, in a verse (M II 3, 107) that sums up the feeling about God. Human thought is a limitation, and when the theosophical mystics of the school of Ibn ‘Arabī tried to describe Him in terms that point simultaneously to His transcendence and His immanence, this is nothing but a faint attempt to describe Him, the deus absconditus, whom one can approach at best by ‘seizing the hem of His Grace’, that is, to describe one of His manifestations which cover His Essence like garments, like veils. How is one to speak about the One who is absolutely transcendent and yet is closer to mankind than their jugular vein (Sūra 50:16), so that the mystics found Him at the end of the road, in the ‘ocean of the soul’ and not in the mosque, not in Mecca or in Jerusalem? Poems have sung of Him in colourful images, in paradoxes, negations and affirmations which, however, do nothing but hide the transcendent Essence, for He is, so to speak, the ‘Super-Unknowable’.

On the philosophical side, the Ismailis have tried to maintain His transcendence by using a double negation freeing the idea of God from all association with the material and removing Him also from the association with the non-material. God is thus neither within the sensible world nor within the extrasensible.12

He is, in the Koranic expression, ‘the First and the Last, the Inward and the Outward’ (Sūra 57:3), and the mystery of His being is summed up in Sūra 59:23–4:

He is God besides whom there is no deity, the One who knows the visible and the invisible. He is the Merciful, the Compassionate. He is God, besides whom there is no deity, the King, the Holy, the Giver of Peace, the Faithful, the Protector, the Mighty, the Overpowering, the Very High. Praised be God who is above what they associate with Him. He is God, the Creator, the Form-giver; His are the Most Beautiful Names. He is praised by what is in the heavens and on Earth and He is the Mighty, the Wise.

Similarly, the Throne Verse (Sūra 2:255) has served to describe Him to a certain degree, and the concept of His Throne on which He dwells (Sūra 7:54; 10:3 et al.) and which comprises Heaven and Earth has evoked many commentaries, from realistic descriptions to visions of a seat of chrysolite or ruby13 to the mystical interpretation that the true Divine Throne is the human heart, for the ḥadīth qudsī promises: ‘My heaven and My Earth do not comprise Me, but the heart of My faithful servant comprises Me’ (M no. 63).

The God as revealed in the Koran is a living God, who has invited mankind to call Him and He will answer (Sūra 40:62, cf. 2:186), an active, creating and destroying, maintaining and guiding God who is yet beyond any human understanding. He is, in a certain way, a ‘personal’ God, for He has addressed humankind and revealed Himself to them, but the term shakhṣ, ‘person’, cannot be applied to Him.

When looking at the active, powerful Lord of the Koran, one wonders how scholastic theologians could define Him in rational terms: the ‘aqīda sanūsiyya, a dogmatic creed from the fifteenth century which was largely used among Muslims, describes God with forty-one qualities, ṣifāt. Six are basic qualities of which the first and essential one is existence, then further pre-eternity (azaliyya), eternity (abadiyya), His being different from what has become in time, His self-subsistence and the fact that He needs neither place nor originator.

He has a further seven necessary qualities which are: Power, Will, Knowledge, Life, Hearing, Seeing and Speech, and seven accidental qualities, that is: His being powerful, being willing, being knowing, being living, being hearing, being seeing and being speaking (this differentiation emerged from early theological discussions between the Mu‘tazilites and traditionists about His attributes).14

Against these twenty qualities are posited twenty others that are impossible, that is, the contrary of the previous ones: He cannot be not-hearing or not-eternal. His forty-first quality is that it is possible for Him to do or not to do everything possible. Thus the living God as described in the Koran was transformed into a set of definitions with which the normal believer could not establish a true relationship. But definitions of this kind became a central part of normative thinking.

On the other hand, the ḥadīth qudsī in which God appears as a ‘hidden treasure who wanted to be known’ became the focal point among mystically-minded Muslims. But while God is usually seen and experienced as me One who does not need anything, al-ghanī, ‘the Self-sufficient, Rich’, the moving myth of the Divine Names who longed to manifest themselves and to be reflected in the world leads to the feeling that God (at least on the level of the deus revelatus) needs the creatures and mat, in the last instance, God and man are as it were interdependent—an idea often found in mystical speculations everywhere in the world but, understandably, contrary to the convictions of traditionist Muslims who maintained God's supreme rulership and self-sufficiency.

God has been described as the wājib al-wujūd, ‘He whose existence is absolutely necessary’ and upon whom everything relies. One could also transform the simple statement of the shahāda into the phrase la mawjūda illā Allāh, ‘There is nothing existent save God’, for He is the only One upon whom existence can be predicated, and He is the only One who has the right to say ‘I’.15

The concept of waḥdat al-wujūd, ‘Unity of Existence’ as formulated by the commentators of Ibn ‘Arabī, would be expanded (by losing its necessary sophisticated connotations!) into the simple statement hama ūst, ‘everything is He’, which was used in Persian mystical poetry, for example in ‘Aṭṭār's verse, before Ibn ‘Arabī's time and which permeates later Sufi thought in the entire Persianate world. But those who used it usually forgot that the opposite of unity of Existence is kathrat al-‘ilm, ‘the multiplicity of knowledge’, that is, the infinite number of created things which are reflections of God's knowledge and hence different from His Essence.16

God is the prima causa, and there are no secondary causes: He works through what looks like secondary causes just as a tailor works with a needle or a calligrapher works with a pen, and thus it is He who is the real Creator of the design. Again, as He has a name by which He called Himself in me Koran, that is, Allah, He is, as Iqbāl states, an Ego, the highest all-embracing Ego in which the smaller egos of the created universe live like pearls in the ocean, and who contains infinite possibilities in a Presence that transcends created time.

The tension between Divine transcendence and immanence, between theologically defined impersonality and experienced personality, is reflected in a variety of sayings, verses and extra-Koranic Divine words. The ḥadīth qudsī ‘My Heaven and My Earth do not comprise Me but the heart of My faithful servant comprises Me’ (AM no. 63) points to this problem. He is incomparable, beyond every possibility of being grasped by human thought, and the human being, His slave, cannot talk about Him but by ta‘ṭīl, keeping Him free from all human comparisons and not admitting the slightest possibility of an analogia entis; but when one thinks that He made Adam His khalifa, His vicegerent on Earth, and made him alive with His breath, one uses tashbīh, comparison with human concepts. Both aspects reflect the Divine, for man is both slave and representative, and God's attributes of majesty, jalāl, and beauty, jamāl, which are related to each other like man and woman, as it were, form the fabric of the created universe. The tendency of pairing concepts, of speaking in polarities, seems typical of Islamic thought. The Creator is one, but He reveals Himself both in ethical concepts (as orthodoxy sees Him) and in aesthetic concepts (according to the Sufis’ experiences). Infidelity and faith, kufr and īmān are, as Sanā'ī sings, ‘only doorkeepers at the sanctuary of His Unity and Oneness’.17

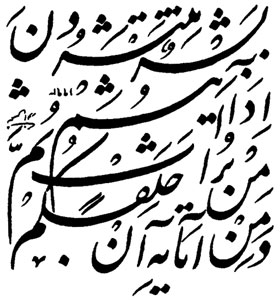

Although the ‘looks do not reach Him’ (Sūra 6:103), we know of Ibn ‘Arabī's vision of the letter A, the last and essential letter of Allāh, which points to His huwiyya, ‘He-ness’—He, who had revealed His words in the letters of the Koran, could be ‘seen’ only in a symbol taken from the letters, from the Book.18

Perhaps, one may say with the poets, He can be seen with the heart's eye:

I saw my Lord with my heart's eye and asked:

‘Who are You?’ He answered: ‘You’.19

God's Absolute Oneness seems to make it impossible for a human being to profess that there is ‘no deity but God’, for the very act of pronouncing this formula already means establishing duality—as Anṣārī says:

No-one confesses the One as the One,

for everyone who confesses Him as the One denies Him.

The mystics knew that (as Dārā Shikōh phrases it):

From saying ‘One’ one does not become a monotheist—

The mouth does not become sweet from saying ‘sugar’.20

Human existence was seen by these radical monotheists as ‘a sin to which nothing is comparable’—only the One exists. Yet, one should distinguish here between the overwhelming spiritual vision of the lover who sees nothing but the beloved and hides his names in all names that he or she mentions—as did Zulaykhā, according to Rūmī's wonderful description at the end of the Mathnawi (M VI 4,023ff.)—and between the attempt to ‘explain’ this experience, to fetter it in philosophical terms and conceptualize it in high-soaring systems which confuse the reader (and here I intend the traditionist as well as the intoxicated lover) more than they enlighten him.

From whichever angle one tries to understand the All-powerful, the All-majestic and All-merciful One God, one should certainly listen carefully to the verse in which Sanā'ī has God speak:

Whatever comes to your mind mat I am that—I am not that!

Whatever has room in your understanding that I would be like this—

I am not like this!

Whatever has room in your understanding is all something created—

In reality know, O servant, that I am the Creator?21

The Koran speaks of God as Creator, Sustainer and Judge; but how can one imagine His creative activity?22

Ancient religions sometimes speak of created beings as ‘begotten’ by the deity, a concept which, on the level of mystical and philosophical speculation, might be described as ‘emanation’—an idea not unknown among Muslim philosophers and mystical thinkers. Creation could also be seen as the deity's victory over the chaos: God is the One who shapes and forms a previously existent matter to fit it into His wise plan. Finally, there is the creatio ex nihilo, a creation owed to the free will of God and hence emphasized by the prophetic religions.

The Koran states that God created the world in six days (Sūra 57:4 et al.) without getting tired, but there is also the idea of a constant creation out of nothing: the long deliberations in Rūmī's work about ‘adam,23 a concept perhaps to be translated best as ‘positive Not-Being’ capable of accepting form, show how much he, like other mystical thinkers, pondered the mystery of Creation, which might be taken as an actualization of contingent ‘things’. Such ideas led Ibn ‘Arabī and his followers to the mythical definition that God and the non-existent things are as it were male and female, and the existent thing that results can be regarded as a ‘child’.24 Rūmī speaks in similar connections of the ‘mothers’, for everything touched by a creative force engenders something that is higher than both.

But in whatever way one wants to explain creation, one knows from the Koran that He needs only say Kun, ‘Be! and it is’ (Sūra 2:117 et al.). For He creates by His Power, as normative theology states.

More than that: the Koran insists that the world has a deep meaning, for ‘He has not created it in jest’ (Sūra 21:16). That is why it obeys Him and worships Him with everything that is in it (Sūra 51:56). And yet, it was also felt—in the succession of Ibn ‘Arabī—that God takes the created universe back into Himself to ‘exhale’ it again; in infinitesimally short moments, the world is as it were created anew, and nothing exists that is not subject to constant though invisible change. Poets and thinkers sing endless hymns of praise to the Creator whose work amazes everyone who has eyes to see, and they ask in grand poems:

Who made this turquoise-coloured turning dome

without a window or a roof, a door?

Who granted stripes to onyx from the Yemen?

From where comes fragrance of the ambergris?25

All the miracles that the seeing eye perceives in the created universe point to the necessity of God's existence; they are His signs, āyāt, which he placed into the world (cf. Sūra 41:53).26

The events in the created world are effects of the Creator's direct involvement: whatever happens is not the result of causality but rather the sunnat Allāh, the Divine custom which can be interrupted at any moment if He decrees so. That is why one has to say in shā Allāh, because one is aware that God can change things and states in the wink of an eye. One also does not praise the artist when admiring a work of art or some special performance but exclaims mā shā Allāh (Sūra 18:39) or subḥān Allāh to praise the One whose wondrous activity shows itself through His creatures; and the pious author will describe his successful actions as minan, ‘Divine gifts’ for which he owes gratitude.

God is One, but with creation, duality comes into existence, and from duality, multiplicity grows. The mystics found an allusion to this truth by discovering that the Divine address kun, written in Arabic kn, consists of two letters and is comparable to a two-coloured rope, a twist, which hides the essential unity from those who are duped by the manifold manifestations. Polarity is necessary for the existence of the universe, which, like a woven fabric, is capable of existence only thanks to the interplay of God's jalāl and jamāl, the myslerium tremendum and the mysterium fascinans, by inhaling and exhaling, systole and diastole. Azal, eternity without beginning, and abad, eternity without end, are the poles between which the world pulsates; Heaven and Earth, ghayb, ‘unseen’, and shahāda, ‘the visible things’ (cf. Sūra 9:94), point to this dual aspect of the created universe as do the concepts of lawḥ, the Well-preserved Tablet (Sūra 85:22), and qalam, the primordial Pen (Sūra 68:1), which work together to write the creatures’ destiny.

The idea that God created the world by His word in one moment or, according to another counting, in six days, was paralleled by the mystical concept of the ‘hidden treasure’. Ibn ‘Arabī developed the myth of the longing Divine Names which, utterly lonely and so to speak ‘non-existent’, that is, not yet actualized in the depths of the Divine, longed for existence and burst out in an act comparable to Divine exhalation. The Names manifested themselves in the universe, which thus became their mirror; contingent being received existence as soon as it was hit by the Name which was to be its rabb, ‘Lord’. Creadon is thus a work of Divine love, but also of Divine self-love—God longed to see His beauty in the mirror of the created things.27

The breath by which this manifestation took place is the nafas ar-raḥmān, the ‘breath of the Merciful’, which is, so to speak, the substance of Creation: pure Mercy and pure Existence are, as it were, the same in the visions of the Ibn ‘Arabī school.

The sudden outbreak of the Divine breath may be called a mystical parallel to the modern Big Bang theory; in either case, one cannot go behind that moment, and the Divine that caused it remains absolutely transcendent while we see ‘as through a looking-glass’. Non-discerning people admire only the highly decorated reverse side of the mirror (medieval steel mirrors were often artistically decorated); they enjoy ‘the world’ without recognizing the face of the mirror which can reflect the eternal beauty. By doing so, they are clearly branded as infidels because, according to the Koran, the world, dunyā, is embellished for the infidels (Sūra 2:212). While the Muslims are called to see God's marvels in creation as pointing to Him, and to listen to the adoration of everything created, they are also warned, in the Koran, not to rely upon the dunyā, ‘this world’, which is usually contrasted with al-ākhira, the Otherworld, the Hereafter. This world, so the Koran states, was created for play and jest (Sūra 57:20). The pleasure derived from the world and its use is but small (Sūra 4:77 el al.), for the world cheats humankind (Sūra 3:185 et al.)—that is why it appears in traditional images often as a cunning, lecherous old hag who attracts lovers to kill them afterwards. For the dunyā is the power which can divert humans from the Hereafter (Sūra 87:16), and those who prefer it to the future life (Sūra 2:86, 4:74) or love it more (Sūra 14:3, 16:107) are warned and called upon to repent.28

Therefore, this world was often blamed by the sage; Ibn Abī Dunyā's book Dhamm ad-dunyā is a good example of this genre. Sufi handbooks abound in such blame, and the aversion to the ‘world’ permeates much of Sufi-minded literature.

On the other hand, one should keep in mind that the world—even if it be worth only a gnat's wing (AM no. 645)—is God's creation, and gives human beings an environment where they can perform worship and improve its conditions: ‘do not ruin the world after it has been set straight’ (Sūra 7:56), warns the Koran, and modern Muslims have taken this āya as a command to work for the improvement of the environment, for one will be asked how one has practised one's responsibility in the world. For this reason, the normative believer disliked overstressed mortification and that kind of tawakkul, ‘trust in God’, which left no room for activity:29 Rūmī, practically-minded as he was, states that ‘negligence’ is also necessary, for if everyone were busy only with ascetic pursuits and works that lead to the Hereafter, how would the world continue and thrive as God had ordered it?

And more than that: the world—again according to Rūmī—is like a tent for the king, and everyone performs his or her work in embellishing this tent: tentmaker and weaver, ropemaker and those who drive in the pegs or the nails are engaged in some work, and their work is their praise for God whose glorification they intend by performing their various occupations. And those who love his world because it proves God's creative power and contains the signs that point to Him are, as Ghazzālī holds, the true monotheists.30

The myth of the ‘hidden treasure’ was widely circulated among the Sufis. But there is still another creation myth which was not as generally accepted. It is the vision of Suhrawardī the Master of Illumination, according to whom Creation came into existence by means of the sound of Gabriel's wings: the archangel's right wing is sheer light, oneness, mercy and beauty, while his left wing has some darkness in it and points to multiplicity, Divine wrath and majesty; it is directed towards the created universe which, in turn, is maintained through innumerable ranges of angels through whom the primordial light, the Divine Essence kat’ exochén, is filtered down into the universe and finally reaches humankind.31

Suhrawardī's angelology is a central piece of his philosophy, but angels are an important part of creation in general and thus play a great role in the religious cosmos of the Muslims.32 Sūra 35 is called ‘The Angels’, and, in Sūra 2:98, people are mentioned who ‘are enemies of God and the angels, the messengers and of Gabriel and Michael’. Thus, belief in the angels is part of the Muslim creed.

Angels are treasurers of God's mercy; they are imagined to be luminous beings but will die at the end of time, to be resurrected immediately and transferred to Paradise. Angels, so Muslims believe, accompany the mortals at every step (Sūra 13:11), but they do not enter places where a picture or a dog is found. They spread the shade of their wings over saints and martyrs or, in Shia tradition, the imams. They have different occupations: thus four, or eight of them carry the Divine Throne (Sūra 69:17), but their main duty is constant worship; adoration is their food and drink, silence is their speech; yet each group of angels which is engaged in ritual prayer performs only one of the prayer positions. They have no free will, and are obedient: only once, so the Koran tells, did they question God's wisdom, that is, when He announced His intention to create Adam and appoint him as khalifa, ‘vicegerent’ (Sūra 2:30). But after acquiescing to God's will and command, they prostrated themselves before the newly-created Adam. The brief remark (Sūra 2:102) about the disobedient and rather frivolous angels Hārūt and Mārūt offered imaginative exegetes good story material.

Two angels, the kirām kātibīn (Sūra 82:11), sit on the human being's shoulders to note down his actions and thoughts. But there are also nineteen angels under the leadership of one Malik who are in charge of Hell (Sūra 74:30).

Tradition and the Koran know of four archangels. The first is Michael (whose wings, as Muslims believe, are all covered with emeralds); he is in charge of the distribution of nourishment to all creatures, and it was he who taught Adam to answer the greeting of peace with the words wa raḥmatu Allāhi wa barakātuhu, ‘And God's mercy and blessings be upon you’. Michael, so it is told, never laughed after Hell was created.

Most prominent in the Koran is Gabriel who is also called ar-rūḥ al-amīn, ‘the faithful spirit’ (Sūra 26:193), and even rūḥ al-quds, ‘the holy spirit’ (Sūra 2:87, 5:110, 16:102). He lives by looking at God, and he is the messenger in charge of the prophets: as he taught Adam the alphabet and agriculture, he instructed Noah in how to build the ark, offered assistance to Abraham when he was flung into the blazing pyre, and taught David to weave coats-of-mail. But more importantly, he was the one who placed God's word into the Virgin Mary so that she could give birth to Jesus, the Word Incarnate, and likewise brought the revelation to Muhammad, the unstained vessel for the Word Inlibrate. Gabriel accompanied the Prophet on his heavenly journey, but had to stay back at the sidrat al-muntahā (AM no. 444) ‘like a nightingale that is separated from his rose’, as the Turkish poet Ghanizade sang in the seventeenth century.33 The idea that only the Prophet could transgress the limits of the created universe and enter the immediate Divine Presence induced thinkers and especially mystics to equate Gabriel with intellect (or Intellect)—for intellect can lead the seeker in the way towards God, unfailingly and dutifully, but is not allowed into the bridal chamber of Love.

The third archangel, not mentioned by name in the Koran but very popular in Muslim tradition, is Isrāfīl, who will blow the trumpet that starts the Resurrection. For this reason, poets liked to compare the thunder's sound in spring to Isrāfīl's trumpet, which inaugurates the resurrection of flowers and plants from the seemingly dead dust. Others, not exactly modest, have likened their pen's scratching to Isrāfīl's trumpet because they hoped, or assumed, that their words might awaken their slumbering compatriots and cause a ‘spiritual resurrection’. Even the word of a saint or the beloved could be compared to Isrāfīl's trumpet because of its reviving qualities.

The most dreaded archangel is ‘Azrā'īl, the angel of death, who, as Muslims tell, was the only angel who dared to grasp clay for Adam's creation from four parts of the earth, and who will tear out the human soul at the appointed hour and place, gently in the case of a believer, painfully in the case of a sinner. However, as mystics claimed, he has no power over those who have already ‘died before dying’ by annihilating themselves in God.

There is a host of angels with strange-sounding names which are used in incantations and magic prayers, and in Suhrawardī's philosophy, angels are seen as the celestial selves of humans. In the later mystical tradition, an angel Nūn appears, connected with the Pen (cf. Sūra 68:1).

An initial encounter with the angel at the beginning of the spiritual path is common to all visionary recitals, especially in the Persianate world, and Iran has contributed the angelic being Sarōsh to medieval Muslim angelology (at least in the eastern lands of Islam). Sarōsh, an old Zoroastrian angelic being, appears as parallel to Gabriel; but while the archangel brings the Divine word, the religious revelation to prophets, Sarōsh appears usually as inspiring poets.

As important as the angels may be, man is still higher than they because he can choose between good and evil and is capable of development, while the angels are perfect but static, bound to be good. The daring expression that the true lover of God can ‘hunt angels’ occurs in Rūmī's and sometimes in other mystics’ Persian verse. It was taken up, in the twentieth century, by Iqbāl, for whom angels are but a lowly prey for the true believer who is ‘the falcon of the lord of lawlāk’, that is, of the Prophet. Iqbāl has often poetically described how the angels gaze at the Perfect Man and praise him and his position in the universe.34

Angels are created from light; other spiritual beings, however, are created from fire (Sūra 15:27, 55:15). These are the djinns and devils. Sūra 72 deals with the djinns. They can embrace Islam, and Muslims believe that marriages between djinns and humans are possible and legally permitted—perhaps the name of the grammarian Ibn Djinnī (d. 1002) points to this belief. Sulaymān, king and mighty prophet, ruled over the djinn as he ruled over all kinds of creatures, and numerous incantarions and talismans against spirits of sorts are prepared in his name, for he was able to imprison some particularly nasty specimens of mat race in bottles which he then sealed and cast into the ocean. The ‘fairy in the bottle’ has lived on to this day in fairytales, romances and television films.

Among the spirits, Iblīs, diabolus, Satan, occupies a special place. He too is God's creature, and never appears as God's enemy or an anti-divine power. He was the teacher of the angels, credited with thousands of years of perfect obedience, but his pride made him claim to be superior to Adam (Sūra 38:76) as fire is superior to clay. His refusal to fall down before Adam, a logical outcome of his pride, was nevertheless interpreted differently: according to al-Ḥallāj and his followers, Iblīs preferred to obey God‘s eternal will that nobody should prostrate himself before anything but Him, and not His outspoken command to fall down before Adam. Caught between Divine will and command, he emerges as a tragic figure and became the model of the true lover who would rather accept his beloved‘s curse man disobey his will35—an idea that even reached the remote Indus Valley, where Shāh ‘Abdul Laṭīf sang: ‘āshiq ‘azāzīl—‘‘Azāzīl [i.e. Satan] is the true lover’.36

This interpretation was, however, restricted to a very small group of Sufis, for usually Iblīs represents the one-eyed intellect who did not see the Divine spark in Adam but only the form of clay.

Nāṣir-i Khusraw, speaking of the ‘devils of [his] time’, that is, the people who seem to corrupt the true faith, thinks that nowadays devils are of clay rather than of fire—an idea that is also found in Iqbāl's highly interesting satanology. Iqbāl considers Iblīs as a necessary force in life, because only by fighting him in the ‘greater Holy War’ can one grow into a perfect human being. In a remarkable poetical scene in the Jāvīdnāma, Iqbāl translated Iblīs's complaint that man is too obedient to him and thus constantly blackens his, Satan's, books while he longs to be vanquished by the true Man of God to find rescue from the Divine curse. Iblīs makes life colourful as the jihād against him gives human life a meaning; and, as Iqbāl says in a very daring Urdu verse, Iblīs ‘pricks God's side like a thorn’, while his ‘old comrade’ Gabriel and the angels are complacent and obedient and thus do not contribute much to make life interesting or worth living.37

Iqbāl's approach to Iblīs is probably inspired by a famous ḥadīth in which the Prophet, asked how his shayṭān, his ‘lower soul’ fared, answered: aslama shayṭānī, ‘My shayṭān has surrendered himself [or: has become a Muslim] and does only what I order him’. That means that, by educating one's lower faculties by sublimating the nafs, one can achieve positive results just as a converted thief will make the best policeman because he knows the tricks of the trade and how to deal with insubordinate people. That is why Iqbāl's Iblīs longs to be trained and educated by a true believer.

Iblīs, similar to Goethe's Mephistopheles, remains under God's command and can be overcome by human striving. This idea, as well as the fact that Islam does not accept the concept of original sin, led a number of critics to the conclusion that Islam does not take seriously the problem of evil. This seems to be a somewhat questionable viewpoint. Even without the concept of original sin and all the problems that result from it, culminating in the necessity of redemption, the thought of man's weakness, sinfulness and his tendency to prefer the ephemeral pleasures of this world to the good ordained by God permeates the Koran, and evil is certainly a problem which is discussed, even if only in the emphasis on istighfār, ‘asking for forgiveness’, and the numerous prayers in which generations of Muslims have confessed their sins, shivering in fear of God's punishment and yet hoping for His grace because the gate of repentance remains open until the sun rises from the West (AM no. 390). This attitude becomes clear when one thinks of the eschatological part of the revelation. It is absolutely clear from the Koran that the world is transient—everything that is in it will perish save God's countenance (Sūra 28:88; cf. 55:26f.).

Is death not sufficient as a warner? The Muslims asked this repeatedly; every day, one sees how humans, animals, plants and even the firm-looking mountains die and decay. Hence the only thing that really matters is to prepare oneself for the day when one will meet one's Lord. For: ‘Everyone will taste death’ (Sūra 29:57 et al.). Ghazzālī's Ilyā' ‘ulūm ad-dīn is nothing but a slow preparation for the moment when one has to face God. The way to that dreaded moment is facilitated—so Ghazzālī may have pondered—by guiding the Muslim through the traditional forty steps (in the forty chapters of his book) and teaching the requirements for a life that, as one may hope, will lead to heavenly bliss. All knowledge, as Muslims know, is only accumulated to prepare the human being for the Hereafter. Only those who have longed all their life to meet with their spiritual Beloved may look forward to death, for ‘death is the bridge that leads the lover to the Beloved’38 and ‘Death is the fragrant herb for the believer’ (AM no. 364).

When the Muslim passes through the last agony, the profession of faith is recited into his or her ears so that he or she can answer the questions which Munkar and Nakīr, the angels in the grave, will ask; for those who answer correctly, the grave will be wide and lofty, while sinners and infidels will suffer in the narrow, dark hole and be tormented by snakes and scorpions. Praying a Fātiḥa for their soul or planting a tree on the site of the grave may alleviate their pain.39 The status of the dead between death and resurrection has been variously described: one encounters the idea of the soul's sleep until resurrection, as also the idea of a foretaste of the future life. ‘The tomb is one of the gardens of Paradise or one of the holes of Hell’ (AM no. 433). Dream appearances in which the deceased tells what happened to him or her sound as if one already had a full knowledge of one's future fate without the general Judgment.

But what is this death? Muslims know that ‘everything hastens towards a fixed term’ (Sūra 13:2). Are people not asleep and do they not awake when they die (AM no. 222), as the Prophet said? The feeling that this life is nothing but a dreamlike preparation for the true life in the world to come permeates much of pious thought. However, one should not think that this dream has no consequences—the ḥadīth states clearly that ‘this world is the seedbed for the next world’ (AM no. 338), and one will see the interpretation of one's so-called ‘dream’ in the morning light of eternity. Death could thus be seen as a mirror of one's actions: at this moment, one will see whether one's face is ugly or beautiful, black or white; it is, to use Swedenborg's expression, ‘the unveiling of the true Self’. Death is the fruit of life; it is, as one says in Persian, baghalparwarde, ‘brought up in one's armpit’ so that one will experience the death which one has prepared, unwittingly, during one's lifetime. Rūmī has often dwelt upon these ideas in his verse, and the poems in popular literature that sing of the spinning or weaving of one's gown for the wedding day, that is for the death or resurrection, symbolize the same idea. Those who love God would sing again with Rūmī:

If death's a man, let him come close to me

that I can take him tightly to my breast.

I'll take from him a soul, pure, colourless:

He'll take from me a coloured frock, that's all.

Death could also be seen as a homecoming—be it the nightingale's return to the rose-garden, or the drop's merging into the ocean, its true home.

Death can be seen as spiritual nuptials, and the term ‘urs for the memorial days of a saint's death expresses this feeling. At such an ‘urs, people would come to the site of a saintly person's mausoleum to participate in the dead person's increased spiritual power, although the Prophet warned of the danger of ‘turning a grave into a festive site’. The correct way of visiting tombs, says Shāh Walīullāh, who quotes this ḥadīth, is to read the Koran, pray for the deceased, give alms or manumit a slave in the name of the deceased—that will be credited to his or her soul.40

If individual death suffices as a warning, then the Koranic revelations about the Day of Judgment are meant to strengthen this warning. There is an astounding number of descriptions of the Day, the Hour and the Knocking One in the earliest revelations, which continually point to this horrible event in new, ever more powerful words, sentences and whole Sūras.41 Perhaps the hour is closer than the distance between two fingers (AM no. 350)? Perhaps it will even happen tomorrow…

Sūra 81 is one of the strongest descriptions:

When the sun shall be darkened,

when the stars shall be thrown down,

when the mountains shall be set moving,

when the pregnant camels shall be neglected,

when the savage beasts shall be mustered,

when the seas shall be set boiling,

when the souls shall be coupled,

when the buried infant shall be asked for what sin she was slain,

when the scrolls shall be unrolled,

when Heaven shall be stripped off,

when Hell shall be set blazing,

when Paradise shall be brought nigh,

then shall a soul know what it had produced.

(transl. A. J. Arberry).

The Meccans, practically-minded as they were, did not take seriously the threats of the impending Judgment, let alone the idea of a resurrection; but not only the growth of the human foetus in the womb but also the ‘resurrection’ of plants from the dead earth should be proof enough. That accounts for the abundance of spring poems in which the imagery of resurrection is used, for in spring the trees will be covered with the green silken robes of Paradise.

Many mythological tales and many allegorical stories were woven around the events before and during Resurrection, such as the return of Jesus and the arrival of the Mahdi. But the central image is that of a terrible confusion on a day that is hundreds of years long. In Islamic languages, the term qiyāmat, ‘resurrection’, often means something incredibly confused—kĭyamet koptu in Turkish is ‘everything was upside down, was in a terrible state’. The poets, on the other hand, often complain that a day without the beloved is ‘longer than the day of Resurrection’.

Popular tradition claims that death will be slaughtered in the shape of a ram. This is one of the numerous fanciful tales, but there is much Koranic foundation for other details of the Day of Judgment: first of all, no soul can carry the burden of another soul (Sūra 2:48), for everyone is responsible for his or her actions and, as tradition has it, every limb will testify for or against its owner. The actions which the angel-scribes have noted down in the books will be given in everyone's left or right hand—left for the sinners, right for the pious. These books can be blackened from sins, but are white and radiant thanks to pious and lawful action; likewise, the sinners have black faces and the blessed have white ones (Sūra 3:106 et al.). Poets have sometimes expressed their hope for forgiveness in an image taken from the art of calligraphy; as Oriental ink is soluble in water, they hoped, metaphorically, to wash off the black letters in their book of actions with tears of repentance.

Scales will be put up (Sūra 21:47 et al.), and, as Sūra 99 states even more emphatically, when the earth opens, everyone will see what he or she has done, even if it is as small as a mustard seed. The Balance is, so to speak, an eschatological symbol of justice and equilibrium. It is, however, not completely clear what is actually being weighed on the scales—is it the actions themselves, the book or the person? One has also to face the Bridge, which is thinner than a hair and sharper than a sword's edge. Rūmī has taken up the ancient Iranian concept of the daēna who will meet the soul at the Bridge to guide it—in the shape of a beautiful young girl in case of a pious person, but as an old ugly hag when a sinner arrives. He ingeniously combines this idea with the Koranic descriptions of death and Judgment.

Your good ethical qualities will run before you after your death—

Like ladies, moon-faced, do these qualities proudly walk…

When you have divorced the body, you will see houris in rows,

‘Muslim ladies, faithful women, devout and repenting ladies’.

(Sūra 66:5)

Without number will your characteristics run before your bier…

In the coffin these pure qualities will become your companions,

They will cling to you like sons and daughters,

And you will put on garments from the warp and woof of your works of obedience…

(D no. 385)

In popular traditions, it was assumed that good acts turn into light and that everything assumes a tangible form: sinners may appear as dogs or pigs according to their dirty habits, while the believers’ virtues will come to intercede for them; mosques appear as ‘boats of salvation’ or as white camels to those who have regularly prayed with the community; the rams sacrificed at the ‘id al-aḍḥā will carry the person who offered them across the bridge; the Koran and Islam come as persons, Friday as a young bridegroom, and prayer, fasting or patience will all be there to intercede for those who have cared for them and performed works of obedience.42 Children who died in infancy will bring their parents to the paradisiacal meadows lest they feel lonely; and, most importantly, the Prophet will come with the green ‘banner of praise’, liwā al-ḥamd, to intercede for the sinners in his community (AM no. 225).

While normal believers will be interrogated in the grave, the martyrs will enter Paradise directly and await resurrection in special places, for they ‘are alive with their Lord’ (Sūra 3:169).

The compensation of good and evil posed a problem at some point, because the Mu‘tazilites claimed that God must punish the sinner and reward the pious, which is a position incompatible with the faith in the omnipotent Lord, who must not be asked what He does (Sūra 21:23)—and who could know whether he or she will be among those who are saved?

The world to come is, no doubt, an intensification of this world. Therefore both mistakes and virtuous deeds appear incredibly enlarged in the form of punishments or compensations. Time and again, the Koran points to terrible details of the punishments in Hell, and it was easy for the commentators and even more for the popular preachers to embellish the Koranic data. When in the Koran Hell is mentioned, for example as calling out Hal min mazīd, ‘Is there no more?’ (Sūra 50:30), then it is described in popular tradition as a dragon with 30,000 heads, each of which has 30,000 mouths, and in each mouth are 30,000 teeth, etc. The central characteristic of Hell is the fire, a fire that rages and burns people, whose skin is renewed again and again to make them suffer infinitely (Sūra 4:56). The food of the inhabitants of Hell is the fruits of poisonous trees, zaqqūm (Sūra 44:43), and their drink is all kinds of dirty stuff, such as dhū ghuslayn (as Naṣir-i Khusraw repeatedly states), that is, water in which ablution has been performed twice, therefore very dirty water,43

The descriptions of Hell led the believers to speculate on whether or not these torments would be eternal, for Sūra 11:108–9 says: ‘The damned enter the Fire… to remain therein as long as Heaven and Earth exist, except if God should decree otherwise’, a word that opens doors to different interpretations.

While the Mu‘tazilites regarded eternal punishment in Hell as a logical corollary of God's justice, and Abū Ḥanīfa had claimed that ‘Heaven and Hell are realities never to disappear’, later scholars drew the reader's attention to Sūra 28:88, which states that ‘everything is perishing save the countenance of God’, and to its parallel in Sūra 55:26. That implies, one would think, that even Heaven and Hell, being created, will perish and cease to exist—and might not God ‘decree otherwise’ (Sūra 11:108)? According to a later ḥadīth, one could find consolation in the thought that ‘there will be a day when the floor of Hell is humid and cress will grow out of it’—for there cannot be a limit to God's power and mercy. Did He not make seven gates for Hell but eight doors for paradise to show that His mercy is greater than His wrath (cf. AM no. 64)?

Some thinkers seem to transform Hell into a kind of purgatory. Rūmī's statement in Fīhi mā fīhi points to a wholesome aspect of Hell, strange as it may sound to us:

The inhabitants of Hell will be happier in Hell than they were on Earth because there they remember their Lord.

While all religions seem to compete in describing the horrifying and gruesome aspects of Hell, it seems much harder to describe the joys of Paradise. The ‘sensual’ images of Paradise in the Koran have angered Christian theologians for centuries: the ideal of ‘gardens under which river flow’ (Sūra 2:25 et al.) might be acceptable (and has influenced the architecture of mausoleums surrounded by watercourses), but the large-eyed virgins, the luscious fruits and drinks, the green couches and the like seemed too worldly to most non-Muslim critics.44 Such symbols, of course, are prone to invite crude elaborations, and some descriptions in theological works, let alone popular visions of Paradise, take the brief Koranic words too much at face value and indulge in images of 70,000 rooms with 70,000 beds in each of them, each with 70,000 pillows on each of which 70,000 virgins are waiting, whose beauty and tenderness is then further depicted. One could, however, interpret the houris and the fruits as symbolizing the greatest happiness, that of perfect union with the Beloved, and of the ancient belief that one can attain union with the Holy by eating it (see above, p. 107).

While the descriptions of Paradise were materialized and clumsified by imaginative people, one of the true concerns of the pious was the question of whether or not one could see God in paradise. While the Mu‘tazilites categorically denied such a possibility, the traditional Muslim view was that it is possible, at least at intervals, and the ḥadīth ‘and your Lord is smiling’ was applied to the inexhaustible happiness caused by the inexplicable experience called the ‘smile’ of Divine Beloved.

But the Koran also offers another picture of Paradise, namely that it is filled with laud and praise of God while the blessed exchange the greetings of peace (Sūra 10:10–11; cf. also 36:58). Based on this Koranic Sūra, Abū Ḥafs ‘Omar as-Suhrawardī spoke of the country of Paradise which consists of fields whose plants are praise and laud of God;45 and a century after him, the Turkish bard Yunus Emre sang in the same style:

S ol cernnetin ĭrmaklarĭ

akar Allah deyu deyu…

The rivers all in Paradise

they flow and say Allah Allah…46

The all-too-human descriptions of Paradise and their endless variations in the works of fanciful preachers and poets were criticized by both philosophers and mystics. The philosophers partly denied bodily resurrection (Avicenna) or taught that a simulacrum would be supplied (Averroes),47 or stated that only the soul survives; rather, only the souls of highly-developed thinkers and knowledgeable people will live on, while the simple souls, like grass, are destroyed at death. These ideas, in a different key, resurface in Iqbāl's philosophy.

The Sufis criticized people who rely on the hope of Paradise or fear of Hell and need these feelings, as it were, to stimulate them to worship. Rābi‘a (d. 801) was probably the first to voice her criticism, and wanted ‘to put fire to Paradise and pour water into Hell’ so that these two veils might disappear. Why turn to such veils? After all, human beings are created for God. Alluding to the story that Adam left Paradise because he ate the forbidden fruit or, in Islamic tradition, the grain, one writer asks:

Why would you want to settle in a place which your father Adam sold for a grain?48

Paradise, says Yunus Emre, is a snare to catch human hearts, while five centuries later in Muslim India, Ghālib called the traditional ‘Paradise which the mullah covets: a withered nosegay in the niche of forgetfulness of us who have lost ourselves…’.49

In certain trends, the degrees, darajāt, to which the Koran allusively speaks (Sūra 17:21; cf. also AM no. 306), are understood not as different gardens in Paradise but as alluding to the transmigration of the soul. This interpretation occurs among the early Shia and the Ismailis.

But how to define these degrees? They seem to point to the fact that what the Muslim awaits in the Hereafter is not a static, unchanging immortality:

If our salvation means to be free from quest,

the tomb would be better than such an afterlife—

says Iqbāl.50 As God's perfections are infinite, the climax is also infinite. Tor Andrae in Sweden wrote: ‘To live means to grow—if future life is a real life, then it is impossible that it could be eternally unchangeable, happy bliss’.51 At the same time, Iqbāl, who was not aware of Andrae's work, interpreted old images of Paradise and Hell in modern terms: according to him, man is only a candidate for personal immortality (an idea which was sharply attacked by several Muslim theologians).

For Iqbāl, Hell is the realization of one's failure in one's achievements, while Heaven is a ‘growing without diminishing’ after the individual, who has strengthened himself sufficiently, has overcome the shock of corporeal death.52 Then a new phase begins, entering into ever-deeper layers of the Infinite, for ‘Heaven is no holiday’.53 Once the journey to God is finished, the infinite journey in God begins.

- 1.

A general work is A. Schimmel and A. Falaturi (eds) (1980), We Believe in One God. The Experience of God in Christianity and Islam.

- 2.

Quoted in K. Cragg (1965), Counsels in Contemporary Islam, p. 38.

- 3.

Quoted in K. Cragg (1984), ‘Tadabbur al-Qur'ān’, p. 187.

- 4.

H. Ringgren (1953), Fatalism in Persian Epics, idem (1955), Studies in Arabic Fatalism; W. M. Watt (1948), Free Will and Predestination in Early Islam.

- 5.

Quoted in F. Heiler, Erscheintmgsformen (1961), p. 514.

- 6.

Fazlur Rahman (1966), Islam, p. 45.

- 7.

Daud Rahbar (1960), God of Justice, is the classic.

- 8.

Eric L. Ormsby (1984) Theodicy in Islamic Thought, H. Zirker (1991), ‘Er wird nicht befragt… (Sūra 21:24). Theodizee und Theodizeeabwehr in Koran und Umgebung’.

- 9.

Frederick M. Denny (1984), ‘The problem of salvation’.

- 10.

F. Meier (1990b), ‘Zum Vorrang des Glaubens und des “guten Denkens” vor dem Wahrheitseifer bei den Muslimen’, deals with ‘thinking good of God’.

- 11.

Fīhi mā fīhi, ch. 12.

- 12.

Azim Nanji (1987), ‘Isma‘ilism’, p. 187.

- 13.

M. Horten (1917b), Die religiöse Gedankenwelt des Volkes, p. 70.

- 14.

Frederick J. Barney (1933), ‘The creed of al-Sanūsī’; R. Hartmann (1992), Die Religion des Islams (new ed.), pp. 55–8.

- 15.

P. Nwyia (1970), Exégèse coranique, p. 249.

- 16.

William Chitrick (1992), ‘Spectrums of Islamic thought: Sa‘id al-Din Farghānī on the implications of Oneness and Manyness’. The contrast between waḥdat al-wujūd and kathrat al-‘ilm also occurs in earlier rimes; see R. Gramlich (1983b), At-tajrīd fī kalimat at-tanḥīd. Der reine Gottesglaube, p. 12.

- 17.

Sanā'ī (1950), Ḥadīqat al-ḥaqīqa, p. 60.

- 18.

There may have been other visions as well, such as that of Bahā-i Walad, who ‘saw His forgiveness like a whiteness composed of pearls’: Bahā-i Walad (1957), Ma‘ārif, vol. IV, p. 33.

- 19.

al-Ḥallāj (1931), Dīvān, muqaṭṭa‘ no. 10.

- 20.

Quoted in Bikrama Jit Hasrat (1953), Dara Shikuh: Life and Works, p. 151, quatrain no. xix. The Anṣārī quote is from S. Langier de Beaurecueil, Khwādja ‘Abdullāh Anṣārī (396–481 h/1006–1089) Mystique Hanbalite, 1965.

- 21.

Sanā'ī (1962), Dīvān, p. 385.

- 22.

S. H. Nasr (1964), An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines; H. Halm (1978), Kosmologie und Heilslehre der frühen Isma‘iliyya.

- 23.

See A. Schimmel (1978c), The Triumphal Sun, s.v. ‘adam.

- 24.

S. Murata (1992b), The Tao of Islam, p. 148.

- 25.

Nāṣir-i Khusraw (1924), Dīvān, p. 254; p. 48.

- 26.

Fazlur Rahman (1966), Islam, p. 121.

- 27.

H. Gorbin (1958), L'imagination créatrice, deals with this ‘longing of the Names’ and related problems. See also H. S. Nyberg (1919), Kleinere Schriften des Ibn al-‘Arabi, p. 85.

- 28.

A fine survey of the use of dunyā is in R. Gramlich (1976), Die schiitischen Derwischorden, vol. 2, p. 91ff.

- 29.

B. Reinert (1968), Die Lehre vom tawakkul in der klassischen Sufik, shows the different aspects of ‘trust in God’ and its exaggerations.

- 30.

Ghazzālī (1872), Ihyā' ‘ulūm ad-dīn, part IV, p. 276.

- 31.

Suhrawardī; (1935), Awāz-i parr-i Jibrīl: ‘Le bruissement de l'aile de Gabriel’, ed and transl. by H. Corbin and P. Kraus. For Suhrawardī's angelology in general, see H. Corbin (1989), L'homme et son ange.

- 32.

W. Eickmann (1908), Die Angelologie und Dämonologie des Korans im Vergleich zu der Engel—und Geisterlechre der Heiligen Schrift. Toufic Fahd (1971), ‘Anges, démons et djinns en Islam’.

- 33.

This story is based on a ḥadīth (AM no. 444); an English translation appears in A. Schimmel (1988), And Muhammad is His Messenger, p. 116.

- 34.

Iqbāl (1937), Zarb-i Kalim, p. 133; idem (1936), Bāl-i Jibrīl, pp. 92, 119; idem (1927), Zabūr-i ‘ajam, part 2, p. 16. For the topic, see Schimmel (1963a), Gabriel's Wing, pp. 208–19.

- 35.

Peter J. Awn (1983), Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblis in Sufi Psychology, see also Schimmel (1963a), Gabriel's Wing, pp. 208–19. For a traditional approach, see P. Eichler (1929?), Die Dschinn, Teufel und Engel im Koran.

- 36.

Shāh ‘Abdul Laṭīf (1958), Risālō, ‘Sur Yaman Kalyān’, ch. V, line 24.

- 37.

Iqbāl (1936), Bāl-i Jibrīl, p. 192f. See Schimmel (1963a), Gabriel's Wing, pp. 208–19.

- 38.

Quoted in Abū Nu‘aym al-Iṣfahānī (1967), Ḥilyat al-awliyā, vol. 10, p. 9.

- 39.

Irene Grütter (1956), ‘Arabische Bestattungsbräuche in frühislamischer Zeit’; Cesar W. Dubler (1950), ‘Über islamischen Grab—und Heiligenkult’. F. Meier (1973), ‘Ein profetenwort gegen die totenbeweinung’, deals with the problem of whether or not the dead are suffering when their relatives and friends cry after their death.

- 40.

A useful survey of all the names by which Resurrection and Judgment are known is ‘Resurrection and Judgement in the Kor'an’.

- 41.

The literature about Muslim eschatology is quite large: see D, S. Attema (1942), De mohammedaansche opvattingen omtrent het tijdstip van den Jongsten Dag en zijn voortekenen; Al-Ghazālī (1989), ‘The remembrance of death and the Afterlife…’, transl. by J. T. Winter; R. Leszyinski (1909), Muhammadanische Traditionen über das Jüngste Gericht; L Massignon (1939), ‘Die Auferstehung in der mohammedanischen Welt’; ‘Abd ar-Rahīm ibn Aḥmad al-Qādī (1977), Islamic Book of the Dead, al-Ḥārit ibn Asad al-Muḥāsibī (1978), Kitāb at-tawahhum: Une vision humaine des fins dernières, Taede Huitema (1936), De Voorspraak (shafā‘a) in den Islam; Thomas O'Shaughnessy (1969), Muhammad's Thoughts on Death; idem (1986), Eschatological Themes in the Qur'an; Jane Smith and Yvonne Haddad (1981), The Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection. For a far-reaching problem, see M. Asin Palacios (1919), La escatologia musulmana en la Divina Comedia.

- 42.

M. Horten, Die rehgiöse Gedankenwelt des Volkes, p. 253, also p. 74.

- 43.

M Wolff (1872), Mohammedanische Eschatologie, nach den aḥwālu'l-qiyāma, arabisch und deutsch; J. Meyer (1901–2), Die Hölle im Islam.

- 44.

C. LeGai Eaton (1982), Islam and the Destiny of Man, last chapter, contains a remarkably ‘sensual’ description of Paradise, which seems amazing in a book written recently by a British Muslim, which is otherwise highly recommendable for modern readers.

- 45.

Suhrawardī (1978), ‘Awārif (transl. R. Gramlich), p. 297.

- 46.

Yunus Emre Divanĭ (1943), p. 477.

- 47.

Fazlur Rahman (1966), Islam, p. 119.

- 48.

Sam‘ānī, quoted in S. Murata (1992b), The Too of Islam, p. 65.

- 49.

Ghālib (1969b), Urdu Dīvān, p. 9.

- 50.

A. Schimmel (1963a), Gabriel's Wing, pp. 273–306.

- 51.

Tor Andrae (1940), Die letzten Dinge, p. 93ff., especially p. 99.

- 52.

In his notebook of 1910, Stray Reflections (1961), Iqbāl noted (no. 15); ‘Personal immortality is not a state, it is a process… it lies in our own hands’.

- 53.

Iqbāl (1930), The Reconstruction of Religious Thought, p. 123. See also Schimmel (1963a), Gabriel's Wing, pp. 119–23.