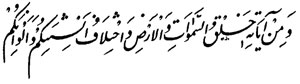

And of His signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth and the difference of your tongues and your colours.

Sūra 30:22

Life consists of numerous actions, many of which are deeply rooted in religious feeling or experience, or are explained by aetiology, as repetition of once sacred events. For actions are thought to gain weight by repetition.1

The custom, sunna, of the ancestors was one of the yardsticks of social life in pre-Islamic Arabic society. After the advent of Islam, the sunna of the founding fathers of the religion regimented all aspects of life. Whatever contradicts or does not conform with the sunna as set as a model by the Prophet is abhorred because it is probably misleading, hence dangerous; thus bid‘a, ‘innovation’, could often be simply classified as mere heresy. The imitatio Muhammadi, as Armand Abel said correctly, consists of the imitation of the Prophet's actions, not, as in the imitatio Christi, of participating in the role model's suffering.

The Koranic revelation itself had emphasized right conduct and salutary action, and to cling to the sunna of the Prophet and the ancient leaders of the community, the salaf, became increasingly important the further in time one was from the first generations who still had a living experience before their eyes. However, the understandable tendency to sanctify the Prophet's example could lead to a fossilization by strictly adhering to given models without realizing the spirit expressed through these models. But while the imitation of the Prophet is termed ittibā‘, or iqtidā, both of which mean ‘to act in conformity with…’ rather than blindly ‘imitating’ and therefore possess a salutary quality, the simple taqlīd, imitation of legal decisions made centuries ago under different social and cultural circumstances, could be dangerous for the growth of a healthy community. Iqbāl blames those who blindly follow the once-and-forever determined decisions:

If there were anything good in imitation,

the Prophet would have taken the ancestors’ path.2

In the framework of inherited values and traditions, classified by theologians and (in part even more strictly) by Sufi leaders, one can discover a tripartition, similar to that in other religions though not as clearly and outspokenly delineated as, for example, in Christianity or Buddhism. It is the organization of material and spiritual life into the via purgativa, via illuminativa and via unitiva, each of which is again divided into steps and various aspects.

VIA PURGATIVA

The via purgativa comprises the different ways of purifying oneself in one's attempt to get in touch with the sacred, the Divine, the Numinous. These include apotropaic rites, such as noise to shy away dangerous powers. That involves, for instance, the use of drums during eclipses to frighten the demons, or, as in parts of Muslim India, gunshots when a son is born in order to distract possible envious djinns from hurting the baby.3 Muslims also use firecrackers (as in the Western tradition) during important and especially liminal times, such as the night of mid-Sha‘bān when the fates are thought to be fixed for the coming year, or in royal weddings, as can be seen in miniatures from Mughal India.

Fumigation is particularly popular: wild rue, sipand, is burnt against the Evil Eye,4 as is storax, tütsü. In former times, Muslims fumigated with the precious ‘ūd, aloes-wood, still used today on rare occasions (thus in Hyderabad/Deccan during the celebrations of the Prophet's birthday or in Muḥarram majilises). Certain kinds of scent were also considered to be repellent to evil spirits and evil influences. The custom of pouring a fragrant lotion over the guest's hands after a meal might originally have had such a protective value.

The idea that scent is an expression of the bearer's character is common in various parts of the world, and the ‘odour of sanctity’ is also known in the Islamic tradition. A story told by both ‘Aṭṭār and Rūmī (M IV 257–305) points to the role of scent as revealing a person's predilection: a tanner came to the perfumers’ bazaar and, shocked by the wonderful fragrance, fainted; he revived only after his brother rubbed some dog excrement under his nose—for the sweet fragrance did not agree with him; he was used only to the stench of the tannery. Thus, evil spirits whose being is permeated with ‘stinking’ characteristics shun the fragrance of incense or fragrant lotions.5

The belief in the Evil Eye,6 which probably belongs among the most ancient concepts in human history, is based, among the Muslims, on Sūra 68:51ff., wa in yakādu, ‘and they nearly had made You glide by means of their eyes’ that is, ill-intentioned enemies directed their eyes upon the Prophet whom God saved from their meanness. And Bukhārī (aṭ-ṭibb 66) states: ‘The Evil Eye is a reality, ḥaqq’. Based on Koranic statements, the words wa in yakādu are often written on amulets against the Evil Eye. Generally, blue beads, frequently in the shape of eyes, are thought to protect people and objects, and the recitation of the last two Sūra, al-mu‘awwidhatān, has a strong protective value. The words a‘ūdhu bi-‘llāh, ‘I seek refuge with God’, act, as it were, as a general protection against evil.

A simple form of averting evil or sending off unpleasant visitors (humans or djinns) is to sprinkle some salt on the floor7 or, as in Turkey, secretly to put some salt in the shoes of a visitor whom one does not want to come again. Salt, however, has a twofold aspect: it preserves food and is highly appreciated as a sign of loyalty, similar to the Western ‘eating bread and salt together’.

One can ward off evil by drawing a circle around the object which one wants to protect; walking around a sick person (usually three or seven times) with the intention of taking his or her illness upon oneself is a well-known custom, which was performed, for example, by the first Mughal emperor, Bābur, who thus took over his son Humāyūn's illness; the heir apparent was indeed healed, while the emperor died shortly afterwards.

Tying knots and loosening them again was a way of binding powers. Therefore, Sūra 113 teaches the believer to seek refuge with God ‘from the women who blow into magic knots’. In some societies, such as Morocco, tattooing is also used to ward off evil.

There are also power-loaded gestures to shy away evil. To this day, a Muslim can be deeply shocked when shown the palm of the right hand with the fingers slightly apart, for this is connected with the Arabic curse khams fi ‘aynak, ‘five [i.e. the five fingers] into your eye’ that is, it means to blind the aggressor. The belief in the efficacy of the open hand is expressed in one of me best-loved amulets in the Islamic world, the so-called ‘Hand of Fāṭima’, a little hand worn as an elegant silver or golden piece of jewellery or else represented in red paint, even drawn with blood on a wall to protect a house. Often, it forms the upper part of Sufi poles or staffs.8 This hand is also connected, especially among Shiites, with the Panjtan, the ‘five holy persons’ (see above, p. 79) from the Prophet's family, and their names. Also, the name of ‘Ali or those of all the twelve imams are sometimes engraved in a metal ‘Hand of Fāṭima’.

If the gesture of showing the open hand to someone is more than just shying away a prospective adversary but involves a strong curse, another way of cursing is connected with the prayer rite: while one opens the hands heavenwards in petitional prayer to receive as it were the Divine Grace, one can turn them downwards to express a curse. An extensive study of gestures in the Islamic world is still required.

A widely-used apotropaic matter is henna, which serves on the one hand to dye white hair and beards, giving the red colour of youthful energy. At weddings, especially in Indo-Pakistan, the bride's hands and feet are painted with artistic designs in the henna (mēhndi) ceremony, and the young women and girls attending the festive night happily throw henna at each other to avert evil influences. For the same apotropaic reasons, henna is also used in the Zar ceremonies in Egypt to keep away the evil spirits and djinns.9 Among Indian Muslims, yellow turmeric can have the same function of protection of the bride, and betel, chewed by so many Indians and Pakistanis, is supposed to contain some baraka (one can even swear on betel).10

But one has not only to use protective means to keep away evil influences; rather, one has also to eliminate negative aspects and taboo matter before approaching the sacred precincts. Here, again, various rites are used to get rid of the evil, the sin, the taboo—whatever may cling to one's body or soul. There is nothing comparable to the scapegoat in Islamic lore, but the custom, known both in the Indian subcontinent and in Egypt, of sending off little rafts or boats of straw into a river is thought to carry off evil. Often, this is done in the name of Khiḍr, and the tiny vehicle is loaded with some lights or blessed foodstuffs over which the Fātiḥa has been recited. This sending-off of evil is usually done at weddings and on festive days. One may even look from the viewpoint of elimination at a well-known historical event: when the ashes of the martyr-mystic al-Ḥallāj were cast into the Tigris after his execution, it was probably not only the external act of getting rid of him, but subconsciously it may also have been hoped that the ‘evil’ influences of the man which might continue to disturb the community should be carried off by the water.

A widely-known rite for eliminating evil is the confession of sins. This custom is unknown in normative Islam, for there is no mediator between God and man to whom one could confess one's sins and be absolved. However, in Sufi and futuwwa circles, a brother who had committed a sin had to confess it either to his master or in front of the brethren, assuming a special ‘penitent's position’ (i.e. keeping his left ear in his right hand and vice versa, with the first toes of each foot touching each other, the left one on the right one).11

One could also try to get rid of any evil that might cling to one's body or soul by taking off one's clothing, especially the belt or the shoes. Moses was ordered ‘to take off his sandals’ (Sūra 20:12) because, in the sacred area which he was called to enter, nothing defiled by ordinary daily life is admitted. The expression khal‘ an-na‘layn, ‘the casting-off of the two sandals’, became a favourite term among the Sufis. One thinks immediately of Ibn Qaṣy's (d. 1151) book by this very tide, but the use is much wider: the seeker would like to cast off not only the material shoes but everything worldly, even the two worlds, in order to enter the Most Sacred Presence of the Lord.

The Turkish expression duada baş açmak, ‘to bare one's head in petition’, is reminiscent of the custom that formerly a sinner wore a shroud and approached the one whose forgiveness he implored barefooted and bareheaded.12 Thus, to take off one's shoes when entering a house and, even more, a mosque is not so much a question of external purity lest the street's dust sully the floor and the rugs but basically a religious act, as the house is in its own way, a sacred place whose special character one has to respect and to honour (see above, p. 49). The finest Islamic example of casting off one's everyday clothes when entering a place filled with special baraka is the donning of the iḥrām, the pilgrims’ dress which enables a person to enter the sacred room around the Kaaba. In pre-Islamic times, the circumambulation of the Kaaba was probably performed naked, as sacred nudity is well known in ancient religious traditions. Islam, however, strictly prohibits nudity, and only a few more or less demented dervishes have gone around stark naked, such as Sarmad, the ecstatic poet of Judaeo-Persian background, who befriended the Mughal heir apparent Dārā Shikōh (d. 1659) and was executed two years after his master in Delhi. As contrary as nudity is to strict Islamic prescriptions, it is nevertheless used as a metaphor in mystical language, and authors like Bahā-i Walad (d. 1231) and his son, Jalāluddīn Rūmī, as well as Nāṣir Muḥammad ‘Andalīb and Sirāj Awrangābādī in eighteenth-century India (to mention only a few), used this term to point to the moment when the everyday world and its objects have, as it were, been discarded and only God and the soul are left in a union attained by the absolute ‘denudation’ of the soul.

A different way of eliminating evil powers is exactly the contrary of taking off one's clothing; namely, covering. As human hair is regarded in most traditions as filled with power (cf. the story of Samson in the Old Testament), women are urged to cover their hair. But this rule is also valid for men, for one must not enter a sacred place with the head uncovered. A pious Muslim should essentially always have his head covered by whatever it be—cap, fez, turban—with a small, light prayer cap underneath. When a prayer cap is wanting and one has to greet a religious leader or any worthy man, or enter his house, one may simply use a handkerchief to avoid offending him.

The problem of what to cover and how to interpret the Koranic statement about the attractive parts which women should veil (Sūra 24:31) has never been solved completely. But even the modem Muslim woman, dressed in Western style, will cover her head when listening to the Koran, even if only with a hastily-grabbed newspaper when she suddenly hears a recitation of the Koran on the radio.

Purification

After the evil influences have been averted and previous sins or taboo matter cast out, purification proper can begin before one draws near the Numinous power, the sacred space.

One way of purification is to sweep a place, especially a shrine; and while pilgrims from India and Pakistan could (and perhaps still can) be observed sweeping quietly and gently ‘Abdul Qādir Gīlānī's shrine in Baghdad, modern Turks have found an easier way to purify the shrine of Ankara's protective saint, Hacci Bayram: one simply vows a broom, which is offered to the keeper of the mausoleum when one's wish has been fulfilled.

The Chagatay minister at the court of Herat, Mīr ‘Alī Shīr Navā'ī (d. 1501), called himself the ‘sweeper of ‘Anṣarī's shrine’ to express his veneration for the Sufi master ‘Abdullāh-i Anṣārī (d. 1089),13 a remark which should not be taken at face value, as little as the hyperbolic expression found in literature that one ‘sweeps this or that threshold with one's eyelashes’ (and washes it perhaps with one's tears). But some credulous authors seem to believe that this was actually done.

Sacred buildings were and still are washed at special times: to wash the Kaaba's interior is the Saudi kings’ prerogative, and many shrines are washed at the annual celebration of the ‘urs. Often, the water is scented with sandalwood or other substances to enhance its purifying power. In Gulbarga, the sandalwood used for such a purification is carried around the city in a festive procession led by the sajjādanishīn of the shrine.

But much more important than these customs is the constant admonition that one has to be ritually clean to touch or recite the Koran, for ‘only the purified touch it’, as Sūra 56:79 states.14 This is taken very seriously: no-one in a state of impurity (thus, for example, menstruating women) may perform the ritual prayer in which Koranic verses are recited. Particularly meticulous believers would not even mention the name of God unless they were in a ritually pure state. Among them was the Mughal emperor Humāyūn, who would avoid calling people by their names such as ‘Abdullāh or ‘Abdur Raḥmān lest the sacred name that forms the second part of the name be desecrated. Similar expressions of veneration are also known when it comes to the Prophet's name: ‘Urfī (d. 1591) claims in his grand Persian poem in honour of the Prophet:

If I should wash my mouth a hundred times with rosewater and musk,

it would still not be clean enough to mention your noble name.15

Purification means, in a certain way, a new beginning on a loftier spiritual level.

The Prophet's biography (based on Sūra 94:1) tells how the angels opened young Muhammad's breast to take out a small black spot from his heart and wash it with odoriferous fluids: this is a very convenient way of pointing to his spiritual purification before he was called to act as God's messenger.16

Purification can be achieved by different means. One, not very frequent in the Islamic world, is by fire. It survives in some areas where, as for example in Balochistan, a true ordeal is enacted in the case of a woman accused of adultery, who has to walk barefoot over burning charcoals. Fire-walking is also practised among some Indian Shiites during the Muḥarram procession: a young Muslim friend from Hyderabad/Deccan joyfully described to me this experience, by which he felt purified and elated. Purification through fire is spiritualized in the image of the crucible in which the base matter of the soul suffers to turn finally into gold—one would have to refer here to the entire, and very wide, alchemical vocabulary of medieval Islam whose centre is, indeed, purification by fire. A branch of this purification—comparable to European midsummer night customs—is jumping through fire at Nawruz, the celebration of the vernal equinox, as is sometimes done in Iran; but there is no obvious ‘Islamic’ aspect to this tradition.

Purification, however, is a central Islamic tradition, based essentially on the Divine order to the Prophet: ‘And your garments, purify them.’ (Sūra 74:4). To be in the water is, as was seen above (pp. 7–8), to be quickened after death, and the use of water before prayer or the recitation of the Koran (and in fact before any important action) is not only a bodily but also a spiritual regeneration.

Modernists claim that the emphasis on proper ablution proves that Islam is the religion of hygiene, but the true meaning is much deeper. To get rid of external dirt is one thing, to purify oneself before religious acts is another; as Niẓāmuddīn Awliyā of Delhi remarked: ‘The believer may be dirty, but never ritually unclean’.17 For this reason, ablution is still to be performed after a ‘normal’ bath or shower. It is recommended, according to a ḥadīth, also in times of anger and wrath, because wrath comes from the fire-born devil, and fire can be extinguished by water (AM no. 243).

Ablution is a sacred action, and for each of its parts—taking the water in one's hand, washing one's face, one's arms, one's feet etc—special prayers are prescribed which point to the role of this or that limb in the religious sphere. A look at the examples in widely-used religious manuals such as Abū Ḥafṣ ‘Omar as-Suhrawardī's (d. 1234) ‘Awārif al-ma‘ārif helps one to understand the deeper meaning of purification.18 Ablution after minor defilements, wuḍū’, is required after sleep and after anything solid, liquid or gaseous has left the lower part of the body. Some legal schools require it after two people of opposite sex, who are not related, shake hands or touch each other's skin. After major pollutions such as sex, emission of semen, menstruation or parturition, a full bath, ghusl, is required during which no part of the body, including the hair, may remain dry. The ablution has to be performed in running water (or by pouring water over one's body), and the volume of the water places, ponds or tanks, as found near mosques, is exactly defined.

Mystics could be induced into ecstasy during the first moment that water was poured over their hands, and one reads of saintly people who would perform ghusl—even without previous major pollution—in the icy waters of Central Asian rivers. Often, such acts were done not only for the sake of ritual purification but also with the intention of educating one's obstinate nafs, the lower sensual faculties, the ‘flesh’. Ghusl should be performed before putting on the iḥrām, and a good number of people like to perform it before the Friday noon prayer. For ritual purity is recommended for every important act; thus one should not sleep with one's spouse in a state of impurity, nor should the mother suckle her baby without previous ablution.

Ablution has been taken as a metaphor into literary language, and poets and mystics alike have called on their readers to wash not merely their bodies, their shirts and their turbans but rather their souls. Nāṣir-i Khusraw says:

One has to wash off rebellion from the soul with (the water of) knowledge and obedience.

He even speaks of the ‘soap of religion’ or ‘soap of intellect’ which is needed to purify the human mind.19

But like all rituals, purification too could be overstressed, and it seems that particularly law-abiding people were obsessed with what can almost be called ‘idolatry of water’. Shabistarī thus writes:

Although the mullah takes sixty kilogrammes of water to make his ablution for prayer,

his head seems hollower than a calabash in Koranic meditation.20

Similarly, the Buddha had made some deprecative remarks about those who concentrate almost exclusively upon ritual cleanliness, for, if water enhanced one's piety, then fishes and frogs would be the most religious creatures on Earth. In ‘Aṭṭār's Manṭiq uṭ-ṭayr, then, the duck refuses to partake in the quest for the Sīmurgh because she is constantly in the state of ritual purity (sitting on the ‘prayer rug of water’) and does not want to spoil this state.

The scarcity of water in Arabia led to the possibility of replacing water by sand in cases of dire need (layammwn).

One of the prerequisites of ritual purity in Islam is the absence of blood: not even the smallest bloodstain must be found on one's clothing during prayer. The Christian concept of ‘being washed in the blood of the lamb’ would be utterly repellent to Muslims. And yet, in the history of Sufism one finds that the martyr-mystic al-Ḥallaj claimed that he had performed his ablution with his own blood; mat is, after his hands and feet had been amputated, he wiped the bleeding hand-stumps over his face. This expression was taken over by later poets for whom this meant the lover's absolute purification through martyrdom. For the body of the martyr, who is killed ‘in the way of God’, that is, in religious war (and on a number of other occasions), is not washed before burial; the blood of the martyr is sacred.

Metaphorically speaking, one can ‘perform the ablution with one's tears’, which flow so profusely that they can serve, as it were, as purifying water streams. Some Sufis even thought that their remorseful weeping served ‘to wash the faces of the paradisiacal houris’.21

Not only during one's lifetime is ablution required before important actions, but also when the Muslim is laid to his or her last rest, the dead body is washed, preferably with warm water (except for martyrs). It is repeatedly related that pious calligraphers who had spent most of their lives in copying the words of the Koran or ḥadīth would carefully collect the pieces of wood mat fell down when they sharpened their reed pens, and these innumerable minute scraps would be used to heat the water of their last ghusl because the baraka of me pens with which they had written the sacred words might facilitate their way into the next world and inspire them to answer correctly the questions of the interrogating angels in the grave.22

As ablution can be spoiled by any bodily impurity, so Muslims feel that one's ritual purity (which is more than the bodily) can also be spoiled by looking at or listening to things prohibited; when a Turkish woman friend of mine saw a couple kissing each other intensely in a crowded street in Ankara, she cried out: ‘abdestim bozulacak’—‘my ritual purity is going to be spoiled!’23

Not only by water or, rarely, fire can one become purified, but also by abstinence, whether from sleep, from food or from sex.

Giving up sleep to perform the nightly supererogative prayers, tahājjud, which are recommended in the Koran (Sūra 17:79), is a custom practised by pious Muslims who enjoy the deep spiritual peace of the nightly conversation with their Lord. Mystically-minded people will use the time between 2 and 4 a.m. to meditate and perform their dhikir. In the Ismaili community, the very early morning hours serve for the daily gathering of the believers in quiet meditation.

Asceticism as such, however, is basically un-Islamic. The aversion of many traditionalist Muslims to exaggerated forms of asceticism is one of the reasons for the tensions between the normative orthodox circles and Sufis. Iqbāl had once stated that asceticism is incompatible with Islam, for ‘the Koran is brimful with life’.24 There is no diabolization of the ‘flesh’ and, as mere exists no priestly caste whose members have to administer the sacrament and therefore have to abstain from sex, celibacy has never been accepted as the norm. Rather, the fulfilment of religious obligations requires that one must not mortify the body because it enables the human being to perform the ritual duties. Thus the Muslim can pray before eating: ‘My intention is to eat this food to strengthen my body so mat I can fulfil God's commands’.25

Yet, both in mainstream Islam and in Sufism, various kinds of abstinence were and are practised. The intentional avoidance of food is, basically, a means to gather greater ‘power’ or baraka by giving up a less important source of power, but the fasting month is not observed for reasons of penitence, nor for atonement, nor for ‘gaining power’, but simply because it is God's decree, hence a duty26—a duty, to be sure, that involved other, spiritual benefits.27 The Sufis, considering fasting to be ‘the food of angels’, often overstressed it both in the form described for Ramadān and additional fast days and in the intake of minimal quantities of food, for ‘hunger is God's food by which he feeds only the elite’ (AM no. 460). Hagiographical literature contains examples of the reduction of food-consumption that sound almost frightening, and yet it is quite possible that the remarkable longevity of a considerable number of medieval Sufis is a result of their utterly abstinent life, which led to an increasing spiritualization. To make fasting more difficult, some Sufis practised ṣawm dā'ūdī, that is, eating for one day normally and fasting on the next day lest me body get used to one of the two forms. In the medieval Maghrib (and perhaps elsewhere too), Sufis knew the ṣawm al-wiṣāl, a forty-day fast which was supposed to lead to the unitive experience.28

During Ramaḍān, the Muslim should not only abstain from food during daytime but also avoid evil thoughts and actions, wrath and anger, trying to follow the old adage takhallaqū bi-akhlāq Allāh, ‘qualify yourselves with the qualities of God’, that is, exchange one's lowly characteristics for better ones until one attains complete equanimity.

Modern interpretations of the fasting in Ramaḍān state that it is a good training in self-control but also a practical way to prove one's solidarity with the hungry in the world. But there has been and still is criticism of the institution of a fasting month, which seems not suited to a modern industrialized society as it makes people unable to work enough during daytime. A typical case is President Bourguiba of Tunisia's attempt to declare work as jihād, a ‘holy war’ against hunger and poverty, claiming that as the rules of fasting are lifted in war times the same should be done for modern hard-working people (see above, p. 68).

Abstinence from sex has never been required in Islam. Although the virginity of the unmarried girl is strictly protected, nevertheless celibacy was never encouraged. On the contrary, marriage is the sunna, the sacred custom of the Prophet's community, and numerous stories tell how the Prophet appeared to a celibate ascetic in a dream, urging him to get married in order to become a real follower of his sunna. Most Sufis blessed by such a dream accepted his order, even though they might consider married life a foretaste of Hell. There were some Sufis who had no interest in marriage; but the majority were certainly not ascetics—‘Abdul Qādir Gīlānī, the epitome of the Qadiriyya ṭarīqa, had forty-nine children.

The positive attitude toward marriage as recommended by the Prophet was probably facilitated by the fact that Islam does not know the concept of an original sin that is inherited from generation to generation through the very act of procreation.

Abstinence is a kind of sacrifice: one abstains from a pleasure and gives up a custom in the hope of obtaining in exchange something more valuable. Characteristic of sacrifice is giving up something particularly dear to please or appease the Divine powers (an idea underlying the ancient sacrifice of the firstborn son).

The replacement of human sacrifice by animal sacrifice is at the centre of the story of Abraham's willingness to offer his son (Isaac, according to the Old Testament; Ismā‘il, according to the Muslims). The Muslim remembers this beginning of a new era without human sacrifice every year at the ‘id ul-adḥā on 10 Dhu ‘l-hijja during the pilgrimage to Mecca when a lamb, a ram or the like is slaughtered. Modern critics as well as ordinary Muslims have often asked why the enormous waste of animals at the pilgrimage site in Mecca was necessary and why every Muslim family at home should slaughter an animal. Would it not be more logical, in our time, to give the price for the animal to the poor instead of distributing the meat and the hides? But the lawyer-divines insist on the slaughtering which is not in the Koran but is sunna because only thus the real intention, the remembrance of the substitution of an animal for a human sacrifice, is re-enacted by the believers.29 The sacrificed lamb or ram—so some people believe—will reappear on Doomsday to carry its owner across the ṣirāt-bridge into Paradise.

The sacrifice of blameless young animals (two for a boy, one for a girl) during the ‘aqīqa, the first haircut of a seven-day-old baby, is part and parcel of domestic rituals, and the sacrifice of a sheep is also customary before a Muslim builds a house or constructs any major building, as one may sacrifice animals at saints’ shrines; the blood is sometimes smeared on the threshold to increase its baraka. Among some Sufi orders, the novice is likened to the sacrificial ram of Abraham: he offers himself completely to the master.

The highest form of sacrifice is that of one's own life, as practised for example by the martyrs of faith. One thinks also of the fidā'is in medieval Islamic history whose appearance is initially connected with the Ismaili groups centred in Alamut (Iran) and northern Syria (the so-called Assassins). However, the disciples of a Sufi shaykh could also willingly perform self-sacrifice at the master's order: a modern example is the Ḥurr, me hard core of dervishes around the Pīr Pāgārō in Sind, who were particularly active from the mid-nineteenth century to the Second World War.30

Self-sacrifice lives on in spiritualized form in mystical tradition: the story of the lover whose beloved tells him that his very existence is the greatest sin, whereupon he immediately dies ‘with a smile like a rose’ (D no. 2,943), is found in different variants in classical Sufi literature. Furthermore, al-Ḥallāj's song ‘Kill me, O my trustworthy friends’ served poets such as Rūmī for pointing to the constant growth and upward movement of the creature, which, by ‘dying before dying’ in a series of self-sacrifices, slowly ‘dies from mineral to become a plant’ (M III 3,901) until it returns to the Divine Essence.

Instead of substituting an animal for human sacrifice, one can also perform a pars pro toto sacrifice; that is, one offers a small part of one's body. The typical form, as it survives in Islam, is the sacrifice of hair,31 beginning with the first haircut of the newborn baby. Both sexes have to shave their pubic hair. The hair is cut before the pilgrimage to Mecca (but is not touched during the ḥajj rites). In former times, a disciple who wanted to enter a certain Sufi order such as the Chishtiyya had all his hair shaved, and to this day dervishes devoted to the tradition of the Turkestani saint Aḥmad Yesewi (d. 1166) shave their heads, while the medieval qalandars and a number of bē-shar‘ dervishes (mat is, those who consider themselves as standing outside the religious prescriptions) used to shave not only the head but every trace of hair, including the eyebrows.

An even more important pars pro toto sacrifice is circumcision, something which originally was probably done to increase the boy's sexual power. The Koran does not mention circumcision, but it was apparently taken for granted, as legend tells that the Prophet was born circumcised. The Turkish name of circumcision, sünnet, shows that it is done according to the Prophet's sunna, while the Arabic term ṭahāra points to the ‘purification’ aspect; the Urdu expression musulmānī shows that it is by circumcision that the boy becomes a full member of the Muslim community. The act is usually performed when the boy is seven or eight years old, so that he is fully aware of its importance, and the pride of now being a true Muslim—as Turkish boys told us with beaming faces—outweighs the moments of pain during the operation. Otherwise, to distract the boys, the adults often organized music, shadow plays and the like, and had a number of boys circumcised together to divert them. The circumcision of the sons of a ruler or grandee were usually celebrated with parades and entertainment.

The question of whether or not the prayer of an uncircumcised man is valid was answered differently. A number of theologians consider it permitted, which is important especially when it comes to adult converts to Islam.

Female circumcision is practised based on a ḥadīth which speaks of the ‘touching of the two circumcised parts’, which requires ghusl. It is probably more widespread than is thought, but is never done as a ‘public feast’.32

The complete sacrifice of one's sexual power by castration was never an issue in Islam. Eunuchs, usually imported from Africa and Europe, were kept for practical reasons, such as guarding the women's quarters. They could also serve in the army and reach high ranks in the military hierarchy; but no religious aim was connected with castration.33 Nor did Islam know the custom of sacred prostitution, which played a considerable role in some other, earlier religious traditions.34

Simpler types of substitute offerings are common: among them are the flowers and sweets which are often brought to a saint's tomb and then distributed to the poor as well as to the visitors; and before setting out for a journey, Indian Muslims might offer to their neighbours and friends special sweets over which the Fātiḥa was recited in the name of a particular saint in the hope of securing a speedy journey.

Such distribution of foodstuffs leads to another kind of ‘sacrifice’ which is central in Islam, namely alms-giving. The prescribed alms tax, which constitutes one of the five pillars of Islam, is called zakāt, a term which is, typically, derived from the root z-k-y, ‘to purify’ and to give it is a true act of purification. However, not only the prescribed alms tax but also alms in general, ṣadaqāt, is important in Islamic piety. Not only material gifts in cash and kind can be ‘sacrificed’, but also ethical behaviour and prayer: one offers oneself completely to God in the hope of receiving His mercy. The finest expression of the sacrificial character of ritual prayer, in which the lower self is slaughtered like a lamb, is found in the story of the Sufi leader Daqūqī in Rūmī's Mathnawī (M III 2,140ff.).

While alms are an exactly organized, legally prescribed action, the gift is a free act of the individual, and yet it can also be seen as a kind of sacrifice. For to give means to part with something that is dear to oneself, to distribute as it were a small part of one's being. Gifts bind people together and thus help in shaping and institutionalizing a community. A person with whom one has shared ‘bread and salt’, as Westerners would say, is supposed to remain loyal, hence the Persian term namak ḥarām, ‘whose salt is prohibited’, for a disloyal person.

One must not forget, however, that the recipient of the gift is under a certain obligation towards the giver. Just as by offering a lamb one hopes to attract Divine grace, the giver—even if secretly or unwittingly—hopes for a reciprocation. The Persian expression bār-i minnat, ‘the burden of owed gratitude’, expressed this feeling on the part of the recipient very well. By giving generously, one's power is strengthened, and therefore one loves to give lavishly; anyone who is blessed with Muslim friends knows the largesse of their generosity and often near-despairs under the burden of gratitude. To give in order to receive underlies (for example) the Panjabi custom of vartan banji, the exchange of gifts in ever-increasing, exactly measured quantities, especially at weddings.35

VIA ILLUMINATIVA

A certain borderline between the profane, which is excluded by the act of purification, and the ritual state, is the niyya, ‘intention’. Every religious act must begin with the formulation of the niyya, and the famous saying ‘Al-a‘māl bi'n-niyyāt’, ‘Works are judged according to the intentions’, does not mean, in the first place, that it is the spiritual intention, as most readers would interpret it, but rather that it is the formulated intent to ‘perform a prayer with three cycles’ or to ‘perform the fasting for the day’. Thus, when I asked a Turkish friend during Ramaḍān whether she was fasting, she simply answered ‘niyyetliyim’, ‘I have formulated the niyya’, that is, ‘I certainly am fasting’.

The customs mentioned hitherto belong to the preliminary rites which prepare men and women for the approach to the Numinous. For even in a religion in which Divine transcendence is as central as in Islam, human beings still crave an approximation to the object of their veneration or love (hence the development of saint-worship), and for this reason some Sufis sought the theophany, tajallī, of the Lord whom ‘the looks can never reach’ (Sūra 6:103) by gazing at a beautiful youth, shāhid, a witness to this invisible Divine beauty.

In certain religions, plays were invented to make a sacred event visible in the here and now. In Islam, this happened only in the ta‘ziya plays among the Shiites, in which the drama of Kerbela is re-enacted and the spectators are as it were participating in this event as though they were really present. This however is, again, a custom incompatible with normative Sunni Islam.

Yet, there are always new attempts to become unified, or at least to come close to the object of devotion or the power that is hidden in it. The simplest way is to touch the sacred object or the saintly person, tabarrukan, for blessing's sake. The believer clings to the helper's skirt, and when Mawlānā Rūmī sings:

O seize the hem of His kindness,

he expresses this feeling in an old symbol. The believer touches sacred objects such as stones, tombs or the threshold and, most importantly, the copy of the Koran in which God's word is contained, or else is softly touched by the saint's or the venerable elder's hand which he may put on the believer's head, or perhaps by some peacock feathers that carry his baraka. The ritualized clasping of hands at the beginning of the Mevlevi samā‘ belongs here.

A typical case of transferring the baraka is the bay‘a, the oath of allegiance given to a Sufi master. The novice takes the master's hand (often in a specially prescribed form of movement), and this act guarantees that the current of blessing that goes back to the Prophet reaches him through the proper channel. If a woman takes the bay‘a, the shaykh may touch her hand or find some other way to transfer the baraka; he may stretch out a rod which she grasps, or make her touch his sleeve, or perhaps place his hand in a bowl with water, lest a direct contact, prohibited by the shari‘a, should happen.

A special kind of transfer of power is the custom called in Urdu balā'ēn lēnā, ‘to take away afflictions’: one passes one's hands over an ailing or suffering person, circles them over the head and then takes them onto one's own body; thus the evil is taken away and blessing power substituted.

An even stronger way to avail oneself of blessing power is kissing. Touching or kissing the feet or knees of elders, of important people or of the mystical leader is common practice, as is the kissing of the threshold at a saint's shrine. The best-known ritual of this kind is the pilgrims’ attempt to kiss the black stone of the Kaaba to partake in its blessing power. The same is true for the practice of kissing the copy of the Koran, filled with the baraka of God's word—and when poets compare their beloved's beautiful face to a pure, flawless Koran copy, the idea that the Koran should be kissed may have played a role in this imagery.36

The kiss between two people is, as was known in classical antiquity, an exchange of souls; the soul, which is often thought to be contained in me breath, comes to one's lips when one expires, and can be restored by the life-giving breath of the beloved. That is why Jesus, whose bream could quicken the dead (Sūra 3:44ff., 5:110ff.), became in poetical language me prototype of the beloved who quickens the near-dead lover with his or her kiss. Mystics like Bahā-i Walad extended the topic of the spiritual kiss to contact with God: ‘Go into God's bosom, and God takes you to His breast and kisses you and displays Himself so that you may not run away from Him but put your whole heart upon Him day and night’.37

As both breath and saliva are fraught with blessing power, the custom of breathing upon someone after reciting a prayer (damīdan, üflemek) is common in the Muslim world. One can also breathe certain religious formulas or invocations over water in a bowl, which thus becomes endowed with healing power. In Shia circles, the invocation Nādi ‘Aliyyan… is frequently used for this purpose, and among the Ismailis the āb-i shifā is ‘healing water’ over which the Imam has breathed to fill it with baraka to bless the believers.

Such attempts at establishing a closer connection with the sacred power and its representative were and still are practised among Muslims; but certain practices are restricted to only a segment of the believers, and are disliked by others. One of these is the sacred dance, which belongs originally to the rites of circumambulation by which one either ‘sains’ an object or tries to participate in its power. Orthodox Muslims are still as averse to dance as a religious experience as were the early Christians—so much so that Origen (d. 254) would claim: ‘Where there is dance there is the devil’.38

Dance, especially the whirling dance, goes together with ecstasy, that state in which the seeker seems to be leaving the earthly centre of gravity to enter into another spiritual centre's attracting power, as though he were joining the angelic hosts or the blessed souls.

Ecstasy could thus be induced by whirling dance, which was practised as early as the ninth century among the Sufis in Baghdad, some of whom would abandon themselves to the rapture caused by music, their ‘hearing’, samā‘.39 Such spontaneous dance is known among a number of mystical fraternities (and has almost become a hallmark of Sufi movements in the West—as much as critical early Sufis disliked it). Samā‘ was institutionalized only in the Mevleviyya, the order that goes back to Mawlānā Rūmī and which was organized in its actual form by his son and second successor, Sulṭān Walad (d. 1312). Rūmī had sung most of his poetry while listening to music and whirling around his axis, and to him the whole universe appeared as caught in a dance around the central sun, under whose influence the disparate atoms are mysteriously bound into a harmonious whole. Thus, to enter the whirling means to come into contact with the eternal source of all movement—so much so, that Rūmī saw even the very act of creation as a dance in which Not-Being leapt forward into Existence (D no. 1,832) when it heard the sweet melody of the Divine question Alastu bi-robbikum?, ‘Am I not your Lord?’ (Sūra 7:172); and this dance which permeates all of nature revives even the dead in their graves, for:

Those who know the secret power

of the whirling, live in God—

Love is slaying and reviving

them—they know it. Allāh Hu!

The mystic might feel the bliss of unification when he had lost himself completely in the circling movement, and thus dance can be seen as ‘a ladder to heaven’ that leads to the true goal, to unification. But, as this goal contradicts the sober approach of normative theologians, who never ceased to emphasize God's Total Otherness and who saw the only way to draw closer to Him in obedience to His commands and revealed law, their aversion to music and dance is understandable.40

VIA UNITIVA

In ancient strata of religion, sexual union was conceived as a symbol for spiritual union, and even the Upanishads, abstract as their teaching may sound in many places, describe the highest bliss as comparable to being embraced by a beloved wife. But as the normative theologians disliked the ecstatic dance as a means to ‘union’, they also objected to a terminology in which ‘love’ was the central concept.41 Nomos-oriented as they were, they sensed the danger of eros-oriented forms of religion which might weaken the structure of the House of Islam. They could interpret ‘love’ merely as ‘love of obedience’ but not as an independent way and goal for Muslims, and expressions like ‘union’ with the One who is far beyond description and whom neither eyes could reach nor hands touch seemed an absurdity, indeed impiety, to them. The theological discussions about the terminology of ‘Love’ continued for a long time in the ninth and tenth centuries, long before the thought of a human being as target of one's love appeared in Sufism—a love which, to be sure, was never to be fulfilled but remained (or at least was supposed to remain) chaste and spiritual. The mystics men became aware that ‘the metaphor is the bridge to Reality’ and that love of a beautiful human being was, as they say, ‘ishq majāzī, ‘metaphorical love’, which would lead to ‘ishiq ḥaqīqī, ‘the true love’ of the only One who was worthy of love.

From this viewpoint, the frank use of expressions like ‘naked union’ in Rūmī's poetry can be understood, and his father Bahā-i Walad, who encourages the soul to cast itself into God's bosom without reluctance, compares the intimacy between God and the soul with an explicit reference to the play between husband and wife in which even the most private parts do not remain hidden.42 Six centuries later, the Sufi master Nāṣir Muḥammad ‘Andalīb in Delhi uses similar words, comparing the soul's union with the Divine Beloved to the experience of the virgin whose hymen is pierced by her husband so that she, accustomed to his gentleness, becomes aware of his power and strength.43 The overwhelming shock of the last ecstatic experience is thus symbolized. It seems also (according to an authentic report by someone who underwent the forty days’ seclusion and spent most of the time in dhikr) that this results in a strong ‘sensual’ and even sexual feeling—a fact which perhaps also accounts for the tendency to describe the final union in sexual imagery.

Although the seekers tried to reach the state of blessed union in this life, the true ‘urs, the ‘wedding’ of the soul, is reached in death when the soul is finally reunited with God.

The Koranic descriptions of Paradise, with the large-eyed heavenly virgins, the houris, can be interpreted as a hint of the highest bliss of spiritual union which cannot be expressed in other terms, just as one explains the joy of sexual union to a child by comparing it with sugar (M III 1,406).

An interesting aspect of this imagery is the concept of the woman soul, which is encountered most outspokenly in the Indian subcontinent.44 The Indian type of virāhini, the longing bride or young wife, was taken over into popular and at times also high literatures of the Muslims in Sindhi, Panjabi and other indigenous languages. Such a choice of images would have been difficult, had not a predisposition existed to compare the soul with a woman. After all, the Arabic word for ‘soul’, nafs, is feminine, and the romantic stories of young women, braving all difficulties on the path that leads them through deserts and mountains or into the depth of the Indus, form excellent symbols of the soul's wandering in the mystical path where she has to overcome the most terrible obstacles to be united, through death, with her pre-etemal bridegroom. The predilection of Sufi writers for the topic of Yūsuf and Zulaykhā (Sūra 12:23ff.) seems to point to the same experience; the love-intoxicated woman who tries to reach Absolute Beauty, and is chastised and—as later legend has it—repents and is finally united with her erstwhile beloved, may have served the mystics as a prefiguration of their own longing. This becomes particularly clear in Rūmī's use of the Zulaykhā theme, through which he seems to express his deepest feelings.45 Many utterances of mystical love become indeed much more meaningful if one recognizes the seeker as the female part who craves for union and longs to be filled with Divine grace. The Beloved, the Lord and eternal King, is the truly acting power, while the mystic is the recipient of His grace: God is, as mystical folk poetry often says, as-Sattār, the ‘One Who Covers’ the lonely woman. That in popular Indo-Pakistani poetry the Prophet appears sometimes as the soul's bridegroom, just as the Imam is the longed-for beloved in Ismaili gināns, is part of this imagery.

These ideas were symbolized by dervishes who donned women's garments to show that they were the Lord's modest handmaidens, and it also underlies, to a certain extent, Rūmī's parable, in Fīhi mā fīhi, of the birth of Jesus in the human being when the soul, like Mary, is pregnant with the Holy Spirit.46 Interestingly, the bond between master and disciple is called among Khāksār dervishes izdiwāj-i rūḥānī, ‘spiritual marriage’, a marriage that shall lead to the ‘engendering of love’.47

The Sufis’ love of and admiration for a beautiful young boy, ideally of fourteen years of age, has been expressed in thousands of lines of poetry and is thus an integral part of the tradition. They love to quote the apocryphal ḥadīth: ‘I saw my Lord in the most beautiful form’ (and, as is often added, ‘with his cap awry’). This admiration of a young, ‘moonlike’ beloved, a shāhid, ‘witness’ to Divine beauty, arose in part from the strict seclusion of women in Muslim society, but could lead also to pederasty, as even early sources state with anger and chagrin. As pederasty was condemned in the Koran (cf. Sūra 27:55f.), the very imagery was disliked by many of the pious, who tried to interpret such allusions as pertaining to women (neither Persian nor Turkish has a grammatical gender). The problem of how then to translate correctly the young beloved with ‘a sprouting green facial down and moustache’ is discussed time and again.48

Sexual union is not the only way to allude to one's union with the Numinous power. One can eat or drink the matter mat carries blessing and sanctity; one can ‘eat power’. When the Muslim boy in southern India at the Bismiliāh ceremony (which takes place when he has reached the age of four years, four months and four days) has to lick the words ‘In the name of God…’ from the slate on which they are written with some blessed stuff such as sandalwood paste, he takes in their power, as does the ailing person who drinks water from a bowl that is inscribed with Koranic verses and formulas of blessing.

The pilgrim who visits saints’ shrines and participates in eating the food that carries, as it were, the saint's baraka is another example of ‘eating the sacred’,49 and the huge cauldron from which everyone, caste or rank notwithstanding, receives some blessed food has certainly played a role in expanding the realm of Islam in areas where food taboos were strict (as is the case in Hindu India). Scraping out the enormous cauldron in Mu‘muddīn Chishtī's shrine in Ajmer is one of the most important rituals during the ‘urs, and people try to scrape some morsels from it without caring whether they burn their fingers.50

Communal meals were and are customary at the initiation ceremonies in Sufi brotherhoods and in the futuwwa, and in certain orders very elaborate communal meals are held once in a while; then one usually takes home some of the food for one's family to give them their share of the blessings. The power that can be ascribed to such food, and here in particular to sweets, is understood from Ibn Battūta's travelogue, when he tells that Rūmī's whole inspiration was caused by a piece of blessed ḥalwa.51 The astounding number of allusions to food in Rūmī's poetry makes this amusing story sound almost correct—and Konya is still famed for its ḥalwa!

Even though the ‘sacramental’ idea of partaking of sacred food may be largely forgotten, the language has still, as so often, preserved the underlying feeling: the Sufi ‘tastes’ or experiences the ‘taste’ of spiritual bliss (dhauq). And may one not be allowed to see in the wondrous fruits which the blessed will eat in Paradise a hint of the Numinous character of ‘spiritual’ blessed food? To reach a higher stage by ‘being eaten’ underlies Rūmī's story of the chickpeas (M III 4,1588ff.).

Although the practices and the symbolism just mentioned are certainly important, much more widespread even than food imagery is the symbolism of drinking. It is indeed a strange paradox that, in a religion that prohibits intoxicants, this particular image became the favourite of pious writers. The Koran first ordered: ‘Don't approach prayer when you are drunk!’ (Sūra 4:43), because intoxication hinders the person from performing the rites correctly; in a later stage of the revelation, wine was completely prohibited (Sūra 5:90); only in Paradise will the believers enjoy sharāban ṭāhūran, ‘a pure wine’ or ‘drink’ (Sūra 76:21).

However, the theme of sacred intoxication (Den helige rusen, as Nathan Söderblom's well-known study is called)52 was an excellent symbol for the spiritual state which German mystics would call Gotessfülle, ‘being filled with God’. Intoxication involves a loss of personal identity; the soul is completely filled with spiritual power, and the boundaries of legal prescriptions are no longer observed.

Ibn al-Fāriḍ's (d, 1235) great Khamriyya, the Wine-Ode, describes the wine of Love which the souls drank before the grapes were created and by which they are guided and refreshed; it makes the deaf hear and the ailing healed.53 It is this wine that is mentioned even in a ḥadīth, according to which God gives to His friends a wine by which they become intoxicated and finally reach union (AM no. 571). It also fills Sufi poetry in manifold variants: ‘the Manṣūrī wine, not the angūrī wine’, as Rūmī says, is the wine by which the martyr-mystic ‘Manṣūrī’ al-Ḥallāj was so intoxicated that he joyfully sacrificed his life in the hope of reaching union with his Beloved, while the grape wine, angūrī, is connected with the Christians (D no. 81) and, to a certain extent, the Zoroastrians. Rūmī also called his friends not to come to his grave without being intoxicated, for the wheat that will grow out of his grave's dust will be drunk; the dough made of it will be equally intoxicated; and the baker who works on it will sing ecstatic hymns—so much is he permeated by the wine of Divine Love. This imagery, praising wine and intoxication, continued through the centuries, and even Ayatollah Khomeini's small collection of Persian verse bears the surprising title Sabū-yi ‘ishq, ‘The Pitcher of Love’.54

Two types of Sufis are often juxtaposed: the sober and the intoxicated. The former are those who fulfil all obligations of the law and the path and are in complete self-control, while the intoxicated prefer the state of ecstasy and often utter words that would be dangerous in a state of sobriety. The borders, however, are not always clearly delineated. Sobriety, again, is of two kinds: the first sobriety is the human being's normal state and can lead, for a moment to an intoxication, a rapture in which the mystic seems to experience the absolute Unity; but when he returns from there, restored to his senses, in his ‘second sobriety’ he sees the whole universe differently—not as one with God but entirely permeated by Divine light.

The symbol of intoxication seems most fitting for the ecstatic state when the wine of Love fills one's whole being and causes infinite happiness—which may, however, be followed by long periods of spiritual dryness.

It is interesting that the imagery of wine and drunkenness is also used to symbolize the Primordial Covenant, mīthāq, in which God asked His creatures: ‘Am I not your Lord?’ (Sūra 7:172), Everyone from the future generations whom God drew from the loins of the children of Adam in pre-eternity had to testify that God is the Lord, lest they deny this when asked on Doomsday. The Sufis saw this moment in poetical imagery as a spiritual banquet in which the wine of Love was distributed to humanity so that everyone received the share which he or she will have in this life. Here, the imagery of wine is used not for the final goal of the mystic's unification with God and his being filled with Him, but rather as the starting point of the flow of Divine grace at the beginning of time. And thus it is written around the dome of Ge—sūdarāz's mausoleum in Gulbarga:

They, intoxicated from Love's goblet,

Senseless from the wine of ‘Am I not?’

Strive at times for piety and prayer,

Worship idols now, and now drink wine…55

The lovers of God are beyond beginningless eternity and endless eternity, there where no place is, all submerged in the Divine Beloved.

- 1.

A recent attempt to interpret various aspects of Islam is M. E. Combs-Schilling (1989), Sacred Performances. Islam, Sexuality, and Sacrifice.

- 2.

Iqbāl (1923), Pqyām-i mashriq, p. 264 (last poem).

- 3.

Jafar Sharif (1921), Islam in India, p. 23.

- 4.

The Wild Rue has lent its name to Bess A Donaldson's very useful (1938) study of Persian customs and superstitions. One may also remember that several mystical works have titles alluding to fragrance, such as Najmuddin Kubrā's Fawā'iḥ al-jamāl, the ‘fragrant breeze of beauty’, or Khwāja Khurd's notes called simply Fawā'iḥ. A translation of Rūmī's Mathnawi is called Pirahan-i Yūsufi, ‘Yusuf's shirt’, to convey the idea that it brings the healing fragrance of the original to the reader whose spiritually blind eyes will be opened just as the fragrance of Yusuf's shirt healed his blind father.

- 5.

For the theme, see E. Lohmeyer (1919), ‘Vom göttlichen Wohlgeruch’. The odour of sanctity is well known in Christianity, and the Muslim should pray, following the ḥadith (AM no. 383): ‘Oh my God, quicken me with the fragrance of Paradise’. In Rūmī's poetry, following the example of Shams-i Tabrīzī, concepts like scent, fragrance and odour play an extremely important role. Rūmī's story of the tanner is inspired by ‘Aṭṭar's Asrānāma (see H. Ritter (1955), Das Meer der Seele, p. 92), where the hero is a sweeper, cleaning the latrines. The connection of fragrance and the ‘scent of acquaintance’ with the Prophet's love of perfume is important, and one even finds that the mawlid: singers in Egypt sometimes sing a ‘perfumed’, ta‘fīr, mawlid: ‘Send down, O Lord, perfumed blessings and peace on his tomb!’ (information from Dr Kamal Abdul Malik, Toronto). I hope to deal with the whole complex of ‘scent’ in my forthcoming book Yusuf's Fragrant Shirt (New York, Columba University Press).

- 6.

S. Seligmann (1910), Der böse Blick, R. Köbert (1948), ‘Zur Lehre des tafsīr über den bösen Blick’ Hiltrud Sheikh-Dilthey (1990), ‘Der böse Blick’ Jan Rypka (1964), ‘Der böse Blick bei Niẓāmī’.

- 7.

E. W. Lane (1978 ed.), Manners and Customs, p. 227.

- 8.

An excellent example of this movement is the title page of Roland and Sabrina Michaud (1991), Dervishes du Hind et du Sind.

- 9.

For the Zār, see Kriss and Kriss-Heinrich (1962), Volksglaube im Islam, vol. 2, ch. 3.

- 10.

Jafar Sharif (1921), Islam in India, p. 62.

- 11.

R. Gramlich (1981), Die schiitischen Derwischorden, vol. 3, p. 26ff.

- 12.

I. Goldziher (1915b), ‘Die Entblössung des Hauptes’. See also A. Gölpĭnarlĭ (1977), Tasauuftan dilimize geüen terimler, pp. 46–7.

- 13.

M. Subtelny (forthcoming), ‘The cult of ‘Abdullāh Anṣārī under the Timurids’.

- 14.

G. H. Bousquet (1950), ‘La pureté rituelle en Islam’. See also the unattributed article ‘What the Shiahs teach their children’ in general: I. Goldziher (1910), ‘Wasser als dämonenabwehrendes Mittel’.

- 15.

‘Urfi (d. 1591), quoted in Sājid Siddīqui and Walī ‘Aṣī (1962), Armaghān-i na‘t, p. 49.

- 16.

H. Birkeland (1955), The Legend of the Opening of Muhammad's Breast.

- 17.

The difference between ‘worldly’ dirt and ritual uncleanliness underlies the story that a Sufi's maidservant in ninth-century Baghdad exclaimed: ‘O Lord—how dirty are Your friends!’ (Jāmī (1957), Nafaḥāt al-uns, p. 621)—and yet a Sufi would never neglect his ritual purity.

- 18.

Suhrawardī (1978), ‘Awārif (transl. R. Gramlich), p. 243f.

- 19.

Nāṣir-i Khusraw (1929), Dīvān, pp. 38, 421, 507, 588, and in (1993) tr. Schimmel, Make a Shield from Wisdom, p. 36. Bakharzī (1966), too, speaks in the Awrād al-aḥbāb, vol, 2, p. 311, of ‘the soap of repentance’.

- 20.

Quoted in L. Lewisohn (ed.) (1992), The Legacy of Mediaeval Persian Sufism, p. 23.

- 21.

Richard Gramlich (1992), ‘Abū Sulaymān ad-Dārānī’, p. 42.

- 22.

See A. Schimmel (1984), Calligraphy and Islamic Culture, p. 180 note 167.

- 23.

According to Kharijite opinion, evil talk and slander require an ablution.

- 24.

Muhammad Iqbāl (1917), ‘Islam and Mysticism’, The New Era, 28 July 1917.

- 25.

F. Taeschner (1979), Zünfte, p. 516.

- 26.

H. Wagtendonk (1968), Fasting in the Koran.

- 27.

A ḥadīth mentioned by Bukhārī (ṣawm 2, 9) claims that ‘the bad breath of one who fasts is sweeter to God than the fragrance of musk’.

- 28.

Oral communication from Professor Vincent Cornell, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

- 29.

See H. Lazarus-Yafeh (1981), Some Religious Aspects of Islam, p. 20: according to the well-known theologian M. Shalṭūt, money cannot be substituted for a sacrifice because the slaughtering of the animal ‘is a statute given by God’.

- 30.

H. T. Lambrick (1972), The Terrorist, gives an excellent introduction into the life and thought of the Ḥurr, based on personal papers and records of the trials which he, as a British official, conducted.

- 31.

I. Goldziher (1886), ‘Le sacrifice de la chevelure des Arabes’.

- 32.

Female circumcision is rather common in Egypt, but is also practised in some Panjabi tribes (see Jafar Sharif (1921), Islam in India, p. 50) and among the Daudi Bohoras.

- 33.

D. Ayalon (1979), ‘On the Eunuchs in Islam’.

- 34.

A reflection of Hindu practices is probably the former custom of ‘marrying’ a girl to the shrine of Lāl Shahbāz Qalandar in Sehwan (Sind), an old Shiva sanctuary. In Sind, girls from noble families are sometimes ‘married’ to the Koran and remain virgins, respected by their families and friends. See R. Burton (1851), Sindh, p. 211.

- 35.

For vartan banjī and many more customs in rural Indo-Pacistan, see the useful book by Zekiye Eglar (1960), A Punjabi Village in Pakistan. The still-prevailing custom of celebrating a wedding as grandly as possible, even if that means incurring heavy debts, reflects the—perhaps subconscious—hope of acquiring more power by spending whatever one can afford (and often cannot afford…).

- 36.

See ERE S.V. Kiss; RGG (3rd ed.) S.V. Kuss.

- 37.

Bahā-i Walad (1957), Ma‘ārif, vol. 4, p, 28.

- 38.

For a general introduction, see W. O. G. Oesterley (1923), The Sacred Dance, G. van der Leeuw (1930), In den Himel ist eenen dans; F. Meier (1954), ‘Der Derwischtanz’ M. Molé (1963) ‘La Danse extatique en Islam’.

- 39.

For the use of dance and music in Rūmī's work, see A. Schimmel (1978c), The Triumphal Sun, and idem (1982a), I am Wind, You are Fire, in general: J. During (1989), Musique et mystique dans les traditions d'Iran.

- 40.

Ibn Ḥanbal mentions even a ḥadīth: ‘I was sent to eradicate musical instruments’.

- 41.

W. Schubart (1941), Religion and Eros; A. Schimmel (1979a), ‘Eros—heavenly and not-so-heavenly—in Sufism’.

- 42.

Compare the chapter ‘Hieroi gamoi’ in F. Meier (1990a), Bahā-i Walad (ch. 23).

- 43.

‘Andalīb (1891), Nāla-i ‘Andalīb, vol. 1, p. 832. The motif of wounding the female by means of an arrow permeates literature and art from classical antiquity. A fine way of pointing to the purely symbolic aspects of ‘bridal mysticism’ is Rūmī's verse that ‘No ablution is required after the union of spirits’ (D no. 2207).

- 44.

The theme of the woman soul as it occurs in the regional languages of Indo-Pakistani Islam has been taken up several times by Ali S. Asani (1991, et al.).

- 45.

See A. Schimmel (1992c), ‘Yusof in Mawlānā Rūmī's poetry’.

- 46.

Fīhi mā fīhi, end of ch. 5.

- 47.

R. Gramlich (1981), Die schiitischen Derwischorden, vol. 3, p. tot.

- 48.

See the remark of Joseph von Hammer (1812–13) in his German translation of Der Diwan des… Hafis, Introduction, p. vii.

- 49.

For the role of dīg and langar, cauldron and open kitchen, among the dervishes, see R. Gramlich (1981), Die schiitischen Derwischorden, vol. 3, p. 49f.

- 50.

See the description in P. M. Currie (1989), The Shrine and Cult of Muin al-Din Chishti of Ajmer, and the article by Syed Liaqat Hussain Moini (1989), ‘Rituals and customary practices at the Dargāh of Ajmer’.

- 51.

Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, Riḥla, translated by H. A. R. Gibb, The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, vol. 2, 1962. For Rūmī's use of ‘kitchen imagery’, see A. Schimmel (1978c), The Triumphal Sun, ch. II.

- 52.

N. Söderblom (1915), Ur religionens historia.

- 53.

A translation of the Khamrrjyya is E. Dermenghem (1931), L'écloge dun vin-poème mystique d'Omar ibn al-Faridh.

- 54.

Published in Teheran (200,000 copies) on the occasion of the fortieth day after Ayatollah Khomeini's death in 1989. Bakharzī (1966, Awrād al-ahbāb, vol. 3, p. 240ff.), as well as virtually all Sufi theoreticians—up to Dr J. Nurbakhsh (1988) in his Sufi Symbolism—explain the frequent use of terms like ‘wine’ (sharāb, mudām) as ‘wine of Love’, and ‘that is the “pure wine”, ash-sharāb aṭ-ṭāhūr’.

- 55.

Gēsūdarāz, in Ikrām (ed.) (1953), Armaghān-i Pāk, p. 151.