Of His signs are the night and the day and the sun and the moon.

Sūra 41:37

INANIMATE NATURE1

From earliest times, human beings have been impressed and often overawed by the phenomena of nature which they observe from day to day in their environment. They certainly felt awe when looking at stones, which never seemed to change and which could easily be taken as signs of power and, at a later time perhaps, as representing eternal strength. In the ancient Semitic religions, stones, in particular those of unusual shape, were regarded as filled with power, mana, and the fascination with stones—expressed in the Old Testament by the story of Jacob and the stone of Bethel—has continued down through the ages.

Turkic peoples were equally fascinated by stones and their mysterious powers: stories about taş bebekteri—stones which slowly turned into children—are frequent in Turkey. Stones are used in rain-producing rituals (especially jade), and small niyyet taşlarĭ serve to indicate whether one's intention, niyya, will come true, which is the case when the stone sticks on a flat surface such as a tombstone.2

Syria and Palestine, the home of the ancient Semitic stone cult, still boast strangely-shaped stones which are sometimes considered to be resting places of saints. In Syria, rollstones are supposed to give some of their ‘power’ to a person over whose body they are rolled. To heap stones into a small hill to make a saint's tomb before it is enlarged into a true shrine seems common practice everywhere, be it in the Near East or in the Indo-Pakistani regions.3

Mythology speaks of a rock which forms the foundation of the cosmos; of green colour, it lies deep under the earth and is the basis of the vertical axis that goes through the universe, whose central point on earth is the Kaaba. The black stone—a meteor—in the south-eastern corner of the Kaaba in Mecca is the point to which believers turn and which they strive to kiss during the pilgrimage, for, as a mystical ḥadīth claims: ‘The Black Stone is God's right hand’.4 This stone, as legend tells, is pre-existent, and, while it was white in the beginning, it turned black from the hands of sinful people who touched it year after year.

However, this black stone, described in wonderful and fanciful images by pious poets, is by no means the only important stone or rock in the Muslim world. The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem is extremely sacred because, so it is said, all the prophets before Muhammad rested there, and the Prophet of Islam met with them at the beginning of his heavenly journey to perform the ritual prayer on this very spot. The stone beneath the actual dome is blessed by Muhammad's footprint, and some traditions even claim that the rock hangs free in the air. At the end of time, Isrāfīl, the archangel, will blow the trumpet that announces resurrection from this very rock. The spiritual—besides the historical—connection between the two sacred places with stones (Mecca and Jerusalem) is evident from the poetical idea that the Kaaba comes as a bride to the Dome of the Rock.5

Not only in Jerusalem can one see the imprint of the Prophet's foot, qadam rasūl. One finds such stones in various countries, often brought home by pious pilgrims especially in India—even Emperor Akbar, otherwise rather critical of Islamic traditions, welcomed the arrival of such a stone which his wife Salīma and his aunt Gulbadan had acquired during their pilgrimage.6 Often, majestic buildings are erected over such stones, which the faithful touch to participate in their baraka and then pass their hands over their body. As early as c. 1300, the reformer Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328) fought against the custom of touching a stone with the Prophet's footprint in Damascus, something that appeared to him as pure superstition, incompatible with the faith in the One God.7

Shia Muslims know of stones with the impression of ‘Alī's foot. A centre of this cult is the sanctuary of Maulali (Mawlā ‘Alī) on top of a steep rock near Hyderabad/Deccan, where one can admire an immense ‘footprint’.

The importance of stones is reflected in the symbolic use of the term. Rūmī compares the lover to a marble rock that reverberates with the Beloved's words and echoes them (D l. 17, 867), but even more important is Ibn ‘Arabī's idea that the Prophet is a ḥajar baht, a ‘pure stone’ on which the Divine message was imprinted, as it were—an idea that continued down through the centuries and which is prominent in the theological work of Shāh Walīullāh of Delhi (d. 1762).8

Stones could serve to express the aspect of Divine Wrath, as in the numerous Koranic references to the ‘stoning’ of disobedient peoples (Sūra 105:4 et al.). In this connection, the ‘stoning of Satan’ is administered during the pilgrimage by the casting of three times seven pebbles on a certain spot near Mina, and Satan is always referred to as rajīm, ‘stoned’, i.e. accursed.

Numerous other customs are connected with stones: thus, among the Persian Khāksār dervishes, it is customary to bind a rather big stone on one's stomach—the sang-i-qanā at, ‘stone of contentment’, which points to the suppression of hunger—for that is how the Prophet overcame his hunger.9 A special role is ascribed to gemstones, some of which were regarded as filled with baraka. Early Muslim scholars had a vast knowledge of mineralogy and enlarged the inherited Greek mineralogical works by their observations. Hence, precious and semiprecious stones play a considerable role in folklore and literature.

It is said that the Prophet himself recommended the use of ‘aqīq, agate or carnelian,10 a stone that was plentiful in Yemen and which therefore became connected with the whole mystical symbolism of Yemen whence the ‘breath of the Merciful’ reached the Prophet (AM no. 195). Muslims still like to wear an agate ring or locket, inscribed with prayer formulas or Divine Names (among the Shias, often with the names of the Panjtan), and later Persian and Urdu poets have compared themselves to an ‘agīq bezel which contains nothing but the name of the Divine Beloved. But not only believers in general like to wear such stones; a twelve-pointed agate (symbolizing the twelve imams of the Shia) used to be worn by the members of the Bektashi order of dervishes (Hacci Bektash Stone).

From ancient times, it was believed that the ruby could avert illness—and indeed, in medical tradition, pulverized ruby was an ingredient of mufarriḥ, ‘something that cheers you up’, a kind of tranquillizer—hence its connection with the beloved's ruby lip, or with ruby-like red wine. A beautiful myth tells that ordinary pebbles, when touched by the sun, can turn into rubies after patiently waiting in the depth of the mines—an idea that came to symbolize the transformation of the human heart which, touched by the sun of grace, can mature during long periods of patience and, by ‘shedding its blood’ in suffering, may be transformed into a priceless jewel.

The emerald is thought to avert evil, but also to blind serpents and dragons. Its green colour—the colour of paradise—gave this stone a special place in Muslim thought. Thus, according to a saying, the lawḥ mahfūẓ, the Well-preserved Tablet on which everything is written from pre-eternity, consists of emerald; it is a true tabula smaragdina, as it is also known from medieval gnostic imagery. Henry Corbin, then, has followed the Sufi path which, at least according to some authors like Simnānī (d. 1335), ends in the light of the emerald mountain: the highest station for the wayfarer who has passed through the blackness of mystical death.11

The sight of mountains has always inspired human hearts, and mountains have often been regarded as seats of deities all over the world. This was, of course, an idea impossible in Islam, all the more so because the Koran has stated that the mountains, though put in their places to keep the earth stable, are yet like clouds (Sūra 27:88) and will be, in the horrors of the Day of Judgment, ‘like combed wool’ (Sūra 70:9). Furthermore, Mt Sinai was shattered by the manifestation of the Lord's grandeur (Sūra 7:143), an event that means for Rūmī that it ‘danced’ in ecstasy (M I 876). Mountains are, thus, nothing but signs of God's omnipresence; they prostrate themselves before God (Sūra 22:18) along with all the other creatures, and yet the feeling that one might find more than a purely earthly experience on certain mountains is attested in the Islamic tradition as well—suffice it to think of Abū Qubays near Mecca, according to tradition the first mountain on earth, which later served as a meeting place of the saints, or of Huseyin Ghazi near Ankara, the site of the shrine of a medieval Muslim warrior saint, and similar places.

One could imagine the high mountains as a liminal area between the created universe and the spacelessness of the Divine (cf. the initial oath of Sūra 52); thus, Mt Qāf was thought of as a mountain encircling the whole earth, even though the sight of the Caucasus or, in Southern Asia, of the Himalayas has certainly contributed to, or sparked off, such ideas. In antiquity, some people tried to imitate the sacred mountains, as for example in the Babylonian Ziggurat; the Malwiyya, the spiral minaret of Samarra in Iraq, may be the result of subconscious memories of this tendency.

The earth was always experienced as a feminine power, and although the concept of ‘Mother Earth’ is not as outspoken in the Islamic tradition as elsewhere, the Koranic words according to which ‘women are your fields…’ (Sūra 2:223) show that the connection was a natural one. Was not Adam made of dust, the soft maternal material which was then to be enlivened by the spirit?12 That is why Iblīs, Satan, claimed superiority over him, as his own origin was fire. And thus, the dervishes might remind their listeners that all existence is dust except the Beloved—after all, man is created from dust (Sūra 22:5 et al.) and will return to dust. Dust has a purifying quality: when water for the ritual ablution is wanting, one can perform the purification with dust, tayammum.

The ancient myth of the hieros gamos, the marriage between heaven and earth which, as it were, preforms human marriage—the ‘sowing of the seed’ into the earth and into the females—surfaces only in some cases, especially in the verse of Rūmī, who takes his imagery from the oldest strata of myths. Although he remarks that ‘the earth like the wife and the sky like the man’ are no longer of interest for the true seeker (D l. 15,525), the lover may yet address the spiritual beloved:

You are my heaven, I am your earth—

You alone know what You've put into me!

(D no. 3,038)

Earth and dust become sanctified by contact with powerful and beloved people, and, humble in themselves, acquire new wealth. Sa‘dī's story about an amazingly fragrant piece of purifying clay, which was permeated with the scent of the beloved who had used it while bathing, points to this feeling. Thus, the dust of sacred places and of mausoleums can bring blessing: prayer beads and little tablets are formed from the mud of Ḥusayn's mausoleum in Kerbela for the use of pious Shiites. The Turkish poet Fuzuli (d. 1556) therefore claims with apparent humility:

My poetry is not rubies or emeralds,

my poetry is dust, but the dust of Kerbela!13

Dust from Kerbela and Najaf, ‘Alī's burial place, was deposited in some mausoleums of Shiite kings in India (thus in the Gol Gunbad in Golconda), just as some dust from Mawlānā Rūmī's tomb in Konya was brought to Iqbāl's mausoleum in Lahore because of the Indo-Muslim philosopher-poet's deep veneration for the medieval Persian mystical poet.

Many visitors to an Indo-Pakistani shrine will have been offered dried-up rose petals and dust from the sarcophagus—and, trusting in the sacred purity of this dust, they dutifully swallow it. Indeed, the dust of saints’ and sayyids’ tombs is the true treasure that a province can boast—when Nādir Shah of Iran came to conquer Sind in 1738, the Hindu minister of the Kalhora rulers countered his requests for an immense indemnity by offering him a small bag containing the most precious thing that Sind had to offer, that is, the dust of saints and sayyids.14

Much more central, however, is the role of water, for ‘We have made alive everything through water’ (Sūra 21:30), and, ‘He has sent down water from the sky…’ (Sūra 13:17), to mention only two prominent Koranic statements with regard to water.15 This water not only has the power of purifying people externally, but also becomes—as in other religious traditions—a fitting symbol for the purification of hearts. Water is constantly quaking and moving—that is, as Kisā’ī thinks, its act of exalting the Lord in unison with all other creatures.

There are numerous sacred springs and ponds in the Islamic world—the Zamzam near the Kaaba gushed forth, as legend has it, when Hagar, left alone with little Isma‘il, was thirsty. The well is forty-two metres deep, and its water is slightly salty. Most pilgrims carry some Zamzam water home in special flasks to make the baraka of the spring available to friends and family; some also dip their future shrouds into the well, hoping that the water's blessing power may surround them in the grave. According to popular tales, the water of the Zamzam fills all the springs in the world during the month of Muaḥarram, while in Istanbul legend has it that some Zamzam water was used to build the dome of the Hagia Sophia; otherwise it would have crumbled.

In Arabic folklore, especially in Syria and Jordan, fountains are generally thought to be feminine, although the type of watery fairies (nixies) known in European folklore seems to be absent from traditional Muslim lore. Salty springs, on the other hand, are regarded as male; that is why barren women bathe there.

Springs are often found near the shrines of saints, and it is likely that the locality of many sacred places was chosen just because of the blessing of a nearby water course or fountain. The tank near Sālār Mas‘ūd's shrine in Bahraich is supposed to cure leprosy. The pond of Mangho Pir near Karachi seems to be a prime example of aetiological legends transforming a weird pre-Muslim sacred spot into a Muslim shrine, for not only is this pond close to the dwelling-place of a thirteenth-century saint, but it also houses a huge number of enormous crocodiles whose ancestor the saint, angered for some reason, produced out of a flower. The large pond at Bāyezīd Bisṭāmī's sanctuary in Chittagong (Bangladesh) is inhabited by utterly repellent white tortoises, and in the same area, in Sylhet, a well filled with fish forms an important part of the sanctuary.

Even if one concedes the necessity for a source of water for ablutions in the vicinity of a shrine-cum-mosque, in such cases ancient traditions still seem to have survived. As far as the water for purification is concerned, its quality and quantity are exactly defined by the lawyer-divines, for to enter the water means to re-enter the primordial matter, to be purified, rejuvenated, reborn after dying—hence, the ablution could become a truly spiritual experience for some Muslims, and the theme of entering the water and being like a corpse moved only by the water's flow is frequent in mystical literature. The old Indian tale of the sceptic who, submerged in water, lived through an entire human life in a single moment has also reached Islam: unbelievers who doubted the reality of Muhammad's nightly journey were instructed in a similar way. The best-known example is the tale of the Egyptian Sufi master Dashṭūṭī, who had the Sultan bend his head into a bowl of water so that he immediately lived through an entire life story.16

One should not shy away from water—it is, after all, its duty, indeed its pleasure, to purify the dirty, as Rūmī emphasized time and again: the water of Grace waits for the sinner. The life-bestowing quality of water led almost naturally to the concept of the Water of Life, the goal of the seekers, far away near the majma‘ al-baḥrayan, the ‘meeting place of the two oceans’, as is understood from Sūra 18:60, 61. The Water of life is found, like a green fountain, in the deepest gorges of the dark land, and only Khiḍr, the prophet-saint, can lead the seeker there, while even great heroes such as Alexander missed the blessed fountain and failed to achieve immortality.

The earth is supposed to rest on water, the all-surrounding ocean, but the Koran also speaks several times of the ocean on which boats travel (thus Sūra 14:32) and of its dangers for travellers (thus Sūra 17:67), who remember the Lord only during the horrors of their journey. One also finds the comparison of the world with foam-flecks (Sūra 13:17), and in another Koranic verse it is stated that the world is ‘decked out fair’ (Sūra 3:14). From this point, it was easy for the Sufis to see the created universe as small, pretty foam-flecks in the immense, fathomless ocean of God—mystics in all religious traditions know this image, especially those with ‘pantheistic’ tendencies. Are not waves and foam peripheral, surfacing for a single moment from the abyss, only to return into it? Rūmī has described this vision:

The ocean billowed, and lo!

Eternal wisdom appeared

And cast a voice and cried out—

That was how it was and became—

The ocean was filled with foam

and every fleck of this foam

Produced a figure like this

and was a body like that,

And every body-shaped flock

that heard a sign from the sea,

It melted and then returned

into the ocean of souls…

(D no. 649)

The journey of the fragile boat, that is ‘man’, which will be shattered by the wave of the pre-eternal Covenant, appears time and again in mystical imagery. Many Sufis, especially those writing in later times, were well aware that there is only one real existence which we experience in different states of aggregate: water, ice, droplet and rain are all the same, for water, being without a form of its own, can accept and produce every form.

The image of the ocean for God (or, in poetry, for Love, which may even be an ‘ocean of fire’) is generally valid, but the Prophet too has been called an ocean in which the Koran constitutes the precious pearl.17 More frequent, however, is the combination of the Prophet with the rain.

For rain was sent down to quicken the dead earth (Sūra 41:39), and it is still called raḥmat, ‘mercy’, in some areas of the Turkish and Persian world. Thus it was easy to find cross-relations between the ‘rain of mercy’ and him who is called in the Koran raḥmatan li’ l-‘ālamīn, ‘Mercy for the Worlds’ (Sūra 21:107). Muhammad himself, as Abū Hạfṣ ‘Omar as-Suhrawardī tells in his ‘Awārif al-ma‘ārif, was fond of the precious rain, and ‘used to turn to the rain to accept blessings from it and said, “One that was still recently near his Lord”’.18

Was the Prophet, sent with a life-bestowing message to his compatriots, not comparable to the blessing, fertilizing rain? This thought inspired some of the finest poems in his honour, especially in the Eastern Islamic world. The Sindhi mystical poet, Shāh ‘Abdul Laṭīf (d. 1752), devoted his Sur Sārang to him, ingeniously blending the description of the parched land that longs for rain with the hope for the arrival of the beloved Prophet, who appears as the rain-cloud that stretches from Istanbul to Delhi and even further. A century later, Mirzā Ghālib in Delhi (d. 1869) composed a Persian mathnāvī about ‘The Pearl-carrying Cloud’, i.e. the Prophet, and towards the end of the nineteenth century Muḥsin Kākōrawī (d. 1905) sang his famous Urdu ode in honour of the Prophet, skilfully blending the theme of the cloud and the ‘rain of mercy’ with time-honoured indigenous Indian rain poetry.19

But rain has yet another aspect to it. It comes from the ocean, rises, evaporating, to the sky, condenses again in the clouds and returns finally to the ocean to be united with its original source or else, as was popularly thought, to become a pearl enshrined by a pure oyster. The latter is often connected with the April rain, and to this day in parts of Turkey drops of April rain are carefully collected and preserved for healing purposes. In medieval times, artisans produced vessels, called in Turkey nisan tasĭ, for this precious rain, which were often beautifully decorated.

As is natural in areas where droughts are frequent and rain is a real blessing, the custom of istisqā, the prayer for rain, is found from the earliest days of Islam; in such cases, the community of believers went out of the town in shabby clothes to implore Divine help. Many stories of saintly people who, in some way or another (sometimes even by threatening God), were able to bring down the heavenly water reflect the important role of the istisqā.

One has, however, to distinguish between the blessing, fertilizing rain and the dangerous sayl, the torrent or flash flood. The Koran says: ‘Evil is the rain of those who have been warned’ (Sūra 26:173), for the Divine wrath can devastate their hearts as a rainstorm ruins the fruits in the orchards. It was the Baghdadian Sufi Abū'l-Ḥusayn an-Nūrī (d. 907) who—probably for the first time in Arabic literature—beautifully described the two kinds of spiritual rain which can descend upon the human heart's garden either to quicken it or to destroy it in the form of terrible hail (Sūra 24:43).20

Most obvious is the danger posed by water, of course, in the deluge which, as is said, began by an overboiling kettle in Kufa and which destroyed all sinful people, while the Ark was taken to heaven (Sūra 29:14). The term baḥr in the Koranic revelation can be interpreted as ‘ocean’ but also as a ‘large river’ such as the Nile; and the Nile—connected with the story of Moses—as well as the Tigris (owing to its situation as the river on which the capital Baghdad was built in the mid-eighth century) are the rivers most frequently mentioned by later authors. Does the Tigris not consist of the tears which Iraq shed after the death of the last Abbasid caliph at the hands of the Mongols in 1258? Thus asks a fourteenth-century Persian poet,21 while Khāqānī, two centuries earlier, had interpreted the mighty river as tears of mourning for the once glorious Lakhmid kingdom of which only the ruins of Seleukia-Ktesiphon were left.22

However, besides this half-realistic use of the river-imagery, rivers also acquired a symbolic meaning. The Shiite theologian Kulaynī in the tenth century seems to have been the first to use the comparison of the Prophet with a mighty river. It is remarkable that Goethe, eight centuries later in Germany and, of course, unaware of this early Arabic text, symbolized Muhammad as a river which, springing from a small, fresh and refreshing fountain, steadily grows and, by carrying with him whatever comes into his way—small brooks, rivulets and rivers—brings them home to the father, the all-embracing ocean. Iqbāl (d. 1938), the Indo-Muslim philosopher-poet, admired Goethe's intuitive understanding of the dynamics of prophethood. He translated (very freely, to be sure) the German poem into Persian. Later, he even assumed the pen name Zindarūd, ‘Living Stream’, to point to his close connection with the spirit of prophetic inspiration.23

Rivers can also become signs of Divine activity. One of the finest expressions of this feeling is the Sindhi poet Qāḍī Qādan's (d. 1551) verse:

When the Indus is in spate then the canals overflow.

Thus the love of my Beloved is too mighty for my soul.24

For the human heart is too narrow to contain all the blessing water of the Divine grace and love.

Rivers, so it is understood, are not only this-worldly: Paradise is described in the Koran at several points (Sūra 48:17 et al.) as ‘gardens under which rivers flow’. The cooling, purifying quality of limpid water is part and parcel of eternal beatitude, and Yunus Emre (d. 1321) rightly sings that the rivers in Paradise repeat the name of God in an uninterrupted litany (see below, p. 238).

Sometimes, four paradisiacal rivers are mentioned, and the structure of many gardens, especially those surrounding a mausoleum or a kiosk, reflects with its four canals the arrangement in the hoped—for Paradise, in which rivers or fountains like kauthar and salsabīl will refresh the blessed.

Water in its different manifestations appears—with only a few exceptions, such as the deluge—as blessing power; fire, however, is generally charged with negative power. The word ‘fire’, used so frequently in the Koran, denotes almost without exception the Hellfire. To be sure, God can transform the burning pyre into a rose-garden, as he did for Abraham, for whom fire became ‘cool and pleasant’ (Sūra 21:69) when Nimrod had cast him into it; but burning is utterly painful, be it real burning in Hell or burning in the fire of separation, of unrequited love, which appears to the longing lover worse than Hellfire. And yet, this burning is necessary for the heart's purification (see below, p. 95). Perhaps some subconscious reminiscences of the Zoroastrian fire cult added to the dangerous aspect of fire in Islam—did not Iblīs boast of his fiery origin as a proof of his superiority over Adam? Later poets would sometimes claim that their hearts were burning in love more than the great fire temples of ancient Iran, while folk poets compared their hearts to the potter's kiln which does not reveal the fire that rages inside.25

However, despite allusions to Hell, fire also has its positive qualities. It gains its specific place by the Divine manifestation through the burning bush on Mt Sinai. This was a wholesome fire, and later poets have tended to compare the red tulip that looks indeed like a flame to the fire on the sacred mountain.

Another expression of the Divine aspect of fire is the frequently-used image of the ‘iron in fire’, a symbol well known in both the Christian and the Indian traditions. Rūmī explains the anā'l-ḥaqq, ‘I am the Truth’ (= I am God) of the martyr mystic al-Ḥallāj (d. 922) by comparing him to a piece of iron in the fire: the red, glowing iron calls out ‘I am fire’, and yet its substance is still iron, not fire (M II 1,3478ff.). For no absolute union between man and God is possible as long as the material, bodily aspects of the creature persist.26

A different use of fire occurs in al-Ḥallāj's story of the moth which, slowly approaching the candle, first sees its light, then feels its heat and finally immolates itself in the flame, to assume complete identification (see below, p. 23). But is it not so—as a later poet asks—that the moth knows no difference between the candle of the Kaaba and that of the idol temple? The end of the road is, in either case, complete annihilation.

Candles are lighted in mausoleums and shrines and used during festive nights in honour of a saint. In Turkey, Muslims used to celebrate kandĭl, ‘candle’, that is the nights of major feasts such as the Prophet's birthday or of his heavenly journey, and the mosques are decorated with artistically illuminated signs and inscriptions. These, formerly of live candles, have now of course been replaced by electric bulbs, and thus the modem woman who formerly might have placed a candle near a sacred place to fulfil a vow may now simply bring a bulb to the saint's shrine or the mosque.

Other fiery manifestations of power and ‘signs of God’ are thunderstorms, lightning (Sūra 30:24) and thunder. The Koran states (Sūra 13:13) that ‘the thunder praises Him’, while for Ibn ‘Arabī, lightning is a manifestation of the Divine Essence. Hence, Divine ‘Flashes’ are symbolized from early times as ‘lightnings’ during which the wayfarer may proceed a little bit, while in the intervals the road is dark and it is not possible to walk—an idea derived from Sūra 2:20. Dangerous as the lightning is, it nevertheless releases the element of fire inherent (according to ancient physiology) in the straw as in other things—thus, it is similar to the fire that immolates the moth which it thereby helps to achieve release from the material world. These ideas, however, belong on the whole to a later development in Islamic thought.27

Much older is the role of the wind, which comes as a promise of His Mercy (Sūra 7:57) because it announces the arrival of rain. The gentle wind carried Solomon's throne (cf. Sūra 34:12), but the icy wind, ṣarṣar, destroyed the disobedient cities of ‘Ad and Thamud (Sūra 69:6 et al.). Thus, the term ṣarṣar becomes a cipher for any destructive power. Many later poets in the Persianate world would boast that the scratching of their pen was like ṣarṣar to destroy their patron's enemies, while others, less boastful, would see the two aspects of God's activity, the manifestations of His jamāl, kindness and beauty, and His jalāl, majesty and wrath, in the two aspects of the wind which destroys the infidels and yet is a humble servant to the prophet Solomon.

One aspect of the kindly wind is the southern or eastern breeze, called nafas ar-raḥmān, ‘the breath of the Merciful’, which reached the Prophet from Yemen, carrying the fragrance of Uways al-Qaranī's piety, as formerly a breeze brought the healing scent of Yūsuf's shirt to his blind father Jacob (cf. Sūra 12:94).

‘God is the light of the heavens and of the earth’ (Sūra 24:35). Thus states the Koran in the Light Verse, and the Scripture emphasizes time and again that God leads people from the darkness to the light, min aẓ-ẓulumāilā’ n-nūr.

Light plays a central role in virtually all religious traditions, and the concept of the light which in itself is too radiantly evident to be perceived by the weak human eyes has clear Koranic sanction.28 In the early days of Koranic interpretation, scholars believed that Muhammad was intended as the ‘niche’ of which the light Verse speaks, as the Divine light radiates through him, and again, the Koran had called him sirāj munīr, ‘a shining lamp’ (Sūra 33:46). As such, he is charged with leading people from the darkness of infidelity and error towards the light. One of the prayers transmitted from him is therefore, not surprisingly, a prayer for light:

O God, set light in my heart and light in my tomb and light before me, and light behind me; light on my right hand and light on my left; light above me and light below me; light in my sight and light in my perception; light in my countenance and light in my flesh; light in my blood and light in my bones. Increase to me light and give me light, and appoint for me light and give me more light. Give me more light!

This prayer has been repeated by the pious for many centuries.

At a rather early stage, Muhammad himself was surrounded with light or even transformed into a luminous being: the light of prophethood was inherited through the previous prophets and shone on his father's forehead when the Prophet was begotten. In the Shia tradition, this light is continued through the imams. Small wonder, then, that Muhammad's birth was marked by luminous appearances, and later stories and poems have never failed to describe the light that radiated from Mecca to the castles of Bostra in Syria—the luminous birth and/or epiphany of the founder of a religion is a well-known theme in religious history (cf. the birth of Zoroaster, the Buddha, or Jesus). For light is the Divine sign that transforms the tenebrae of worldly life.

But not only the birth of the Prophet happened with manifestations of light; even more importantly, the night when the Koran was revealed first, the laylat al-qadr (Sūra 97), was regarded as filled with light. Pious Muslims still hope to be blessed with the vision of this light, which indicated the appearance of the last, all-encompassing revelation.

As for the Prophet, numerous myths grew around his luminous being: his light was the first tiling that God created, and mystics have embellished the concept of the pre-eternal Muhammad as a column of light with ever more fanciful and surprising details which are reflected in mystical songs even in Bengal.29

The symbolism of light is widely used, yet in one case even a whole philosophy of light was developed by a Muslim thinker. This is the so-called ḥikmat al-ishrāq, the Philosophy of Illumination by Shihābuddīn as-Suhrawardī, who had to pay with his life for his daring theories (he was killed in 1191). According to him, ‘existence is light’, and this light is brought to human beings through innumerable ranges of angelic beings. Man's duty is to return from the dark well in the ‘western exile’ where he is imprisoned by matter to the Orient of Lights, and his future fate will be determined by the degree of illumination that he has acquired during his life.30

But this search, the quest for more and more light, is central not only in Suhrawardī's illuminist philosophy; rather, the Koranic statement that man should come from the tenebrae to light led certain Sufi masters to elaborate a theory of the development of the human soul so that an individual, during long ascetic preparations, may grow into a true ‘man of light’ whose heart is an unstained mirror to reflect the Divine light and reveal it to others. Henry Corbin has described this process lucidly in his study on L'homme de lumière dans le soufisme iranien (1971). The equation God = light, based on Sūra 24:35, was natural for Muslims, but it was a novel interpretation of this fact when Iqbāl applied it not to God's ubiquity but to the fact that the velocity of light is the absolute measure in our world.31

The central role of the concept of ‘light’ can also be gauged from the considerable number of religious works whose tides allude to light and luminosity, beginning from collections of ḥadīth such as Ṣāghānī's Mashāriq al-anvār, ‘Rising points of the lights’ or Baghawī's Maṣābīḥ as-sunna, ‘The lamps of the sunna’ to mystical works like Sarrāj's Kītāb al-luma‘, ‘Book of the Brilliant Sparks’, Irāqī's Lama‘āt, ‘Glitterings’ and Jāmī's Lawā'iḥ, ‘Flashes’—each of them, and many more, intended to offer a small fraction of the Divine or the Prophetic light to guide their readers in the darkness of this world.

The most evident manifestation of the all-embracing and permeating light is the sun; but the sun, like the other heavenly bodies, belongs to the āfilīn (Sūra 6:76), ‘those that set’, to whom Abraham turned first until he understood that one should worship not these transient powers but rather their Creator, as Sūra 41:37 warns people ‘not to fall down before the sun and the moon’ but before Him whose signs they are. Islam clearly broke with any previous solar religion, and the order of the ritual prayer takes great care to have the morning prayer performed before sunrise and the evening prayer after sunset lest any connection with sun-worship be imagined (and yet their timing perfectly fits into the cosmic rhythm). The break with the solar year and its replacement by a lunar year underlines this new orientation. Nevertheless, the sun's role as a symbol for the radiance of the Divine or of the Prophet is evident. The ḥadīth has Muhammad say: ‘I am the sun, and my companions are like stars’ (AM no, 44)—guiding stars for those who will live after the sun has set. And in another ḥadīth he is credited with claiming: ‘The hatred of the bats is the proof that I am the sun’—the contrast of the nightly bats, enemies of the sun and of the true faith, was often elaborated, for example in SuhrawardīMaqtūl's delightful Persian fables.32

The Prophet's connection with the sun becomes particularly clear in the later interpretation of the beginning of Sūra 93, ‘By the morning light!’, which was understood as pointing to the Prophet. It was perhaps Sanā'ī (d. 1131) who invented or at least popularized this equation in his long poetical qaṣīda about this Koranic chapter.33 The ‘morning light’ seemed to refer to the Prophet's radiant cheek, while the Divine Oath ‘By the Night!’ (Sūra 92) was taken to mean the Prophet's black hair.

As a symbol of God, the sun manifests both majesty and beauty; it illuminates the world and makes fruits mature, but were it to draw closer it would destroy everything by its fire, as Rūmī says, warning his disciple to avoid the ‘naked sun’ (M I 141).

More important for Islamic life than the sun, however, is the moon, the luminary mat indicates the time. Did not the Prophet's finger split the moon, as Sūra 54:1 was interpreted? And it was this miracle that induced the Indian king Shakravarti Farmāḍ to embrace Islam, as the Indo-Muslim legend proudly tells.34

The moon is the symbol of beauty, and to compare one's beloved to the radiant moon is the highest praise that one can bestow upon him or her. For whether it is the badr, the full moon, or the hilāl, the slim crescent—the moon conveys joy. To this day, Muslims say a little prayer or poem when they see the crescent for the first time; on this occasion, they like to look at a beautiful person or something made of gold and to utter blessings in the hope that the whole month may be beautiful. It is told that the great Indian Sufi Niẓāmuddīn Awliyā used to place his head on his mother's feet when the crescent appeared in the sky, out of reverence for both the luminary and the pious mother. Poets have composed innumerable verses on the occasion of the new moon, in particular at the end of the fasting month, and one could easily fill a lengthy article with the delightful (but sometimes also tasteless) comparisons which they have invented. Thus, for Iqbāl, the crescent serves as a model of the believer who ‘scratches his food out of his own side’ to grow slowly into a radiant full moon, that is, the person who does not humiliate himself by begging or asking others for help.35

It was easy to find connections between the moon and the Arabic alphabet. The twenty-eight letters of the alphabet seemed to correspond to the twenty-eight days of the lunar month. And does not the Koran mention twenty-eight prophets before Muhammad by name, so that he is, as it were, the completion of the lunar cycle? Indeed, one of his names, Ṭāhā (Sūra 20:1), has the numerical value of fourteen, the number of the full moon.

While the moon is a symbol of human beauty, it can also be taken as a symbol of the unattainable Divine beauty which is reflected everywhere: the traditional East Asian saying about the moon that is reflected in every kind of water has also found its way into the Islamic tradition. Thus, in one of Rūmī's finest poems:

You seek Him high in His heaven—

He shines like the moon in a lake,

But if you enter the water,

up to the sky He will flee…

(D no. 900)

Some mystically-inclined Turks even found a connection between the words Allāh, hilāl ‘crescent’ and lāla ‘tulip’, all of which consist of the same letters a-l-l-h and seem therefore mysteriously interconnected.

The stars, although belonging to the āfilin, ‘those that set’, can serve as signs for mankind (Sūra 6:97); they too prostrate before the Lord—‘and the star and the tree prostrate both’ (Sūra 55:6). The importance of the ‘star’ as a mystical sign can be understood from the beginning of Sūra 53, ‘By the Star!’

The stars as guiding signs gained extreme practical importance in navigation, and inspired mathematical and astronomical works in the early centuries of Islam. The great number of astronomical terms in Western languages which are derived from the Arabic prove the leading role of Muslim astronomers. Among the stars that were particularly important were the polar star and Suhayl, Ganopus, and the Pleiades, as well as Ursa Major, which often appear in literature. The Koran speaks also of shooting stars, shihāb, which serve to shy away the devils when they try to enter the heavenly precincts (Sūra 72:8–9).

Astronomy went along with astrology, and the properties of the zodiacal signs (as they were known from classical antiquity as well as from Oriental lore) were taken over and elaborated by Muslim scientists. Niẓāmī's (d. 1209) Persian epos Haft Paykar, ‘The Seven Pictures’ or ‘Beauties’, is the best example of the feeling that everything is bound in secret connections—stars and days, fragrances and colours. Those who had eyes to see could read the script of the stars in the sky, as Najmuddīn Kubrā (d. 1220/1) informs his readers, and astrological predictions were an integral part of culture. Thus arose the use of astrologically suitable names for children, a custom still practised in parts of Muslim India, for example. Indeed, it is often difficult to understand the different layers of Islamic poetry or mystical works without a certain knowledge of astrological traditions, and complicated treatises such as Muhammad Ghawth Gwaliorī's (d. 1562) Jawāhir-i khamsa, ‘The Five Jewels’, point to astounding cross-relations involving almost every ‘sign’ in the universe. The ancient tradition of interpreting the planets—Jupiter as the great fortune, Saturn as the (Hindu) doorkeeper of the sky, Venus as the delightful musician, etc.—was used by artists at many medieval Muslim courts. There is no dearth of astrological representations on medieval vessels, especially on metal.

Astrology, as it was practised by the greatest Muslim scientists such as al-Bīrūnī (d. 1048), offered believers another proof that everything was part of cosmic harmony—provided that one could read the signs. But when it came to the sky itself, the ancient idea that this was the dwelling-place of the High God could not be maintained. The sky is clearly a symbol pointing to Divine transcendence, because God is the creator of the seven heavens and of the earth; and, as the Throne Verse (Sūra 2:255) attests, ‘His Throne encompasses heavens and earth’. The heaven is, like everything else, obedient to God's orders, bending down before His Majesty. And yet, one finds complaints about the turning spheres, and Muslims seem to join, at times, the remarks of their predecessors in Iran and ancient Arabia for whom the turning wheel of the sky was connected with cruel Fate (see below, p. 32).

Light and darkness produce colours. Here, again, one enters a vast field of research. The combination of the different stars with colours, as found in Niẓāmī's poem, is not rare—as Saturn is the last of the then known planets and its colour is black, ‘there is no colour beyond black’. The luminous appearances which the Sufi may encounter on his spiritual path are again different, and so are the seven colours which are observed in mystical visions in different sequences.36 One thing, however, is clear: green is always connected with Paradise and positive, spiritual things, and those who are clad in green, the sabzpūsh of Persian writings, are angels or saints. This is why, in Egypt, Muslims would put green material around tombstones: it should foreshadow Paradise. Green is also the colour of the Prophet, and his descendants would wear a green turban. Thus, green may constitute, for example, in Simnānī's system, the eternal beatitude which, manifested in the emerald mountain, lies behind the black.

Dark blue is the ascetic colour, the colour of mourning. Red is connected with life, health and blood; it is the colour of the bridal veil that seems to guarantee fertility, and is used as an apotropaic colour. Red wine, as well as fire (in its positive aspects) and the red rose, all point to the Divine Glory, as it is said that the ridā al-kibriyā, ‘the cloak of Divine Glory’, is radiant red.

Yellow points to weakness, as the weak yellow straw and the pale lover lack fire and life-giving blood; in its honey-coloured hue, yellow was used for the dresses of the Jews during the Middle Ages.37

A full study of the colour symbolism of the Sufi garments is still required. Red was preferred by the Badawiyya in Egypt, green by the Qādiriyya, and the Chishtis in India donned a frock whose hue varied between cinnamon and rosy-yellowish. Whether some masters wore cloaks in the colour that corresponded to the colours that they had seen in their visionary experiences is an open question, but it seems probable.38 But in any case, all the different colours are only reflections of the invisible Divine light which needs certain means to become visible—in the ṣibghat Allāh (Sūra 2:138), ‘the colouring of God’, the multicoloured phenomena return to their original ‘one-colouredness’, a term used by Sufis for the last stage of unification.

PLANTS AND ANIMALS39

The Tree of Life is a concept known from ancient times, for the tree is rooted in the earth and reaches the sky, thus belonging to both spheres, as does the human being. The feeling that life power manifests itself in the growth of a tree, that leaves miraculously sprout out of bare twigs and fruits mature year after year in cyclical renewal, has impressed and astounded humanity through the ages. Hence, the tree could become a symbol of everything good and useful, and the Koran states, for this reason, that ‘a good word is like a good tree’ (Sūra 14:24).

Trees are often found near saints’ tombs: the amazing number of trees connected with the name of ‘Abdul Qādir Gīlānī in Sind was mentioned by Richard Burton and others.40 Visitors frequently use such trees to remind the saint of their wishes and vows by hanging rags—sometimes shaped like minute cradles—on their branches or, as for example in Gazurgah near Herat, driving a nail into the tree's trunk.

It is natural that Paradise, as an eternal garden, should boast its very special trees, such as the Tuba, whose name is developed from the greeting ‘Happiness’, ṭūbā, to those pious people who believe (Sūra 13:29); that is, the Tuba tree is the personified promise of eternal bliss that one hopes for in Paradise. Likewise, the boundaries of the created universe are marked by the Sidra tree, mentioned in Sūra 53:14—the ‘Lote tree of the farthest boundary’, which defines the limit of anything imaginable; and it is at this very Sidra tree where, according to legend, even the mighty Gabriel had to stay back during the Prophet's heavenly journey while the Prophet himself was blessed with reaching the immediate Divine Presence beyond Where and How.

Thinkers and mystics could imagine the whole universe as a tree and spoke, as did Ibn ‘Arabī, of the shajarat al-kawn, the ‘tree of existence’, a tree on which man is the last, most precious fruit. On the other hand, Bāyezīd Bisṭāmī, in his mystical flight, saw the ‘tree of Unity’, and Abū'l-Ḥusayn an-Nūrī, at about the same time, envisaged the ‘tree of gnosis’, ma‘rifa.41

A detailed account of the ‘tree of the futuwwa’, the ‘manly virtue’ as embodied in later futuwwa sodalities, is given in a fifteenth-century Turkish work:42 the trunk of this tree, under which the exemplary young hero lives, is ‘doing good’ its branches are honesty; its leaves proper etiquette and restraint; its roots the words of the profession of faith; its fruits gnosis, ma‘rifa, and the company of the saints; and it is watered by God's mercy.

This is reminiscent of the Sufi shajara, the ‘family tree’ that shows the disciples their spiritual ancestry, leading back to the Prophet: drawings—often of enormous size—symbolize the continuous flow of Divine guidance through the past generations, branching out into various directions.

Some thinkers embellished the image of the ‘tree of the world’ poetically. Probably nobody has used the image of the tree for different types of humans more frequently and extensively than the Ismaili philosopher-poet Nāṣir-i Khusraw (d. after 1072), for whom almost everything created turned into a ‘tree’:

You may think, clever man, this world's a lovely tree

Whose tasty, fragrant fruits are the intelligent…

or else:

The body is a tree, its fruit is reason; lies and ruse

are straw and thorns…43

The close connection between the tree and life, and especially spiritual life, is beautifully expressed in the ḥadīth according to which the person who performs the dhikr, the recollection of God, is like a green tree amid dry trees—a likeness which makes the Muslim reader think immediately of dry wood as fuel for Hell, as it is alluded to in the Koranic curse on Abū Lahab's wife, ‘the carrier of fuel wood’ (Sūra 111:5). Thus Rūmī sings in one of his quatrains:

When the spring breeze of Love begins to blow—

every twig that's not dry begins to move in dance!

For Love can move only the living branches, while the dried-up twigs remain unmoved and are destined to become kindling for Hellfire.

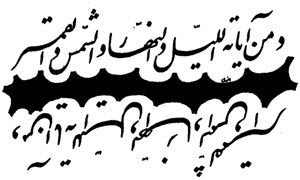

The Tree of Life, whose branches are the Divine Names,44 is rooted in the Divine Presence; or else, the profession of faith can be seen as a tree whose outer rind, formed by the negation lā, is pure negativity, and whose sap flows through the h, the last and essential letter of Allāh (see Figure, p. 19) (M IV 3,1828ff.).

In addition, not only the created universe but also God Himself can be symbolized through a tree: poets, especially in the Indo-Pakistani areas, sang of the tree ‘God’. Qāḍī Qādan in Sind (d. 1551) sees the Divine Beloved as a banyan tree whose innumerable air roots seem to hide the fact that the tree in reality is only one (as the phenomena hide the Divine Unity), while Sulṭān Bāhū in the Panjab (d. 1692) sings of God as the jasmine tree that grows in his heart, watered by the constant repetition of the profession of faith until His fragrance permeates his entire being.45

The shahāda, centred on the essential letter h, with the lā as the ‘outer rind’.

Hence comes the idea encountered in popular traditions, for example, that to plant a tree on someone's grave not only has a practical aspect to it but is also thought to lessen the punishment in the grave and console the dead person. The baraka of a tree can be transferred by touching it or, in certain places, by creeping under a low-bent tree or its strangely-shaped branches; a very typical tree of this kind can be seen near a shrine in Ucch (southern Panjab).

Parts of the tree carry the same baraka as does the whole tree, be it its leaves or its twigs. The custom of beating people—in jest or earnest—with fresh twigs is basically an old fertility rite, which conveys some of the tree's life power. It was practised in medieval Egypt when the jester, ‘ifrīt al-maḥmal, jokingly beat the spectators when the maḥmal on which the cover of the Kaaba was carried to Mecca was paraded in grand style through the streets of Cairo; similar customs can be observed during the Muḥarram processions in Hyderabad/Deccan.

The tree's blessing power is also preserved in the wreath. The custom of garlanding pilgrims returnnig from Mecca or honoured guests is a faint reflection of this feeling of the tree's baraka, as is the garlanding of saints’ tombs; every visitor to major shrines in the subcontinent knows of the numerous little shops that sell flowers and wreaths near the entrance to the sacred places.

Not only does the tree in general bear the flow of vital power, but also specific trees or their twigs play a role in folklore and literature. Sometimes the baraka of such trees is ascribed to the fact that they had grown out of the miswāk, the toothpick of a saint which he threw away and which took root to grow into a powerful tree. A good example is the Junaydi shrine in Gulbarga/Deccan.

On a Koranic basis, it is the date palm which has a special relation with life: the Koranic account of Mary's labour (Sūra 19:236ff.) tells that the Virgin, during her birth pangs, grasped the trunk of a dried-up palm tree, which showered dates upon her as a Divine sign of the Prophet to be born. (The idea has inspired Paul Valéry's beautiful poem La palme.) The Arabs love date palms, and dates were and are used in several dishes prepared for religious purposes, such as the twelve dates in the ḥalwā prepared for feasts in the futuwwa sodalities.46 Another important tradition in the Tales of the Prophets points to the idea that fig trees are protected and should not be burnt, as the fig tree offered its leaves to cover Adam's and Eve's shame after the Fall. And did not God swear in the Koran (Sūra 95:1) ‘By the the fig and the olive’? The olive is even more prominent in the Koran, not only in the Divine Oaths but also as the mysterious tree, ‘neither eastern nor western’ (Sūra 24:35), whose oil shines even without being touched by fire. The cypress is called ‘free’ and reminds Persian and Turkish poets of their beloved's tall, slender stature, while the plane tree seems to resemble a human being—do its leaves not look like human hands which it lifts as if it were in prayer?

Such comparisons lead to the concept of the garden—the garden as a replica of Paradise, Paradise an eternal garden in which every plant and shrub sings the praise of God. The Koran had repeatedly emphasized the reality of resurrection by reminding the listeners of the constant renewal of Nature in spring, when the rains had quickened the seemingly dead earth. Therefore Persian and Turkish poetry abounds in such poems, for the fresh greenery of bushes and trees looked as if Paradise had descended on earth.47

Abū'l-Ḥusayn an-Nūrī in ninth-century Baghdad elaborated the comparison of the heart with a garden filled with fragrant plants, such as ‘recollection of God’ or ‘glorification of the Lord’, while a somewhat later mystic speaks of the ‘garden of hearing’ in which the leaves are of God pleasure and the blossoms of praise.48 The garden of the heart, then, is blessed by the rain of grace, or, in the case of sinners, the rain of wrath destroys its poisonous plants.49 Likewise, one may see human beings similar to plants—some like fragrant flowers, some like grass.

Certain plants are thought to be endowed with special powers: the wild rue, sipand, is used against the Evil Eye (usually in fumigation), and the so-called Peyghamber gul in Afghanistan, a small yellow plant with little dark lines, seems to bear the marks of the Prophet's fingers. But in the Islamic tradition, as elsewhere, the rose has pride of place. The Prophet kissed the rose and placed it on his eyes, for ‘the red rose is part of God's glory, kibriyā’.50 On the other hand, legend claims that the rose grew out of the drops of perspiration which fell from the Prophet's body during his nightly journey—therefore it carries his sweet fragrance.

To the poets, the violet could appear as an old ascetic who, sitting in his dark blue cloak on the green prayer rug, namely the lawn, meditates modestly, his head bent on his knee, while the lily can be interpreted—owing to the shape of its petals—as Dhū ‘l-fiqār, ‘Alī's miraculous sword, or else it praises God with ten tongues. The tulip may appear as a coquettish beau with a black heart, but in the religious tradition it reminds the spectator of bloodstained shrouds, especially those of the martyrs of Kerbela, with the black spot resembling a heart burnt by sorrows.51 In Iqbāl's poetry, on the other hand, it symbolizes the flame of Sinai, the glorious manifestation of God's Majesty, and at the same time it can stand for the true believer who braves all the obstacles that try to hinder his unfolding into full glory.

All the flowers and leaves, however, are engaged in silent praise of God, for ‘there is nothing on Earth that does not praise its Creator’ (Sūra 59:24 et al.), and every leaf is a tongue to laud God, as Sa‘dī (d. 1292) sings in an oft-imitated verse which, if we believe the historian Dawlatshāh, the angels sang for a whole year in the Divine presence.52

This feeling of the never-ending praise of the creatures is expressed most tenderly in the story of the Turkish Sufi, Sünbül Efendi (sixteenth century), who sent out his disciples to bring flowers to the convent. While all of them returned with fine bouquets, one of them, Merkez Efendi, offered the master only a little withered flower, for, he said, ‘all the others were engaged in the praise of God and I did not want to disturb them; this one, however, had just finished its dhikr, and so I brought it’. It was he who was to become the master's successor.

Not only the plants but the animals too praise God, each in its own way. There are mythological animals such as the fish in the depth of the fathomless ocean on which is standing the bull who carries the earth; and the Persian saying az māh ta māhī, ‘From the moon to the fish’, means ‘all through the universe’. However, it is difficult to explain the use of fish-shaped amulets against the Evil Eye in Egypt and the frequent occurrence of fish emblems and escutcheons in the house of the Nawwabs of Oudh. A pre-Islamic heirloom is likely in these cases. While in the Koran animals are comparatively rarely mentioned, the Tales of the Prophets tell how animals consoled Adam after the Fall.

There seems to be no trace of ancient totemism among the Arab Muslims, while in the Turkic tradition names like bughra, bugha ‘steer’ or börü ‘wolf’ could be understood as pointing to former totem animals of a clan. Yet, in some dervish orders, mainly in the off-centre regions of the Islamic world, one encounters what appear to be ‘totemistic’ relics: for example, the ‘Isawiyya in North Africa take a totem animal and behave like it during a certain festival, when a steer is ritually (but not according to Islamic ritual!) slaughtered.53 The identification of cats and dervishes among the Heddawa beggar-dervishes seems to go back to the same roots.54 Although these are exceptional cases, some remnants of the belief in the sacred power of certain animals still survive in Sufi traditions in general. One of them is the use of the pūst or pöste, the animal skin which constitutes the spiritual master's seat in a number of Sufi brotherhoods. When medieval dervishes such as Ḥaydarīs and Jawāliqīs clad themselves in animal skins, they must have felt a sort of identification with the animal.

One problem when dealing with the role of animals in religion is the transformation of a previously sacred animal into an unclean one, as happened for example in ancient Israel with the prohibition of pork, the boar being sacred to the Canaanites. The prohibition of pork is one of the rare food taboos that lives on in Islam. There, however, the true reason for its prohibition is unknown, and it is generally (and partly correctly) attributed to hygienic reasons. Yet, it seems that the ugliness of boars shocks the spectator perhaps even more than the valid hygienic reasons, and I distinctly remember the old Anatolian villager who, at Ankara Zoo, exclaimed at the sight of the only animal of this kind (a particularly ugly specimen, to be sure): ‘Praised be the Lord, who has forbidden us to eat this horrible creature!’ Besides, pigs are in general thought to be related in some way or another to Christians: in ‘Aṭṭār's Manṭiq uṭ-ṭayr, the pious Shaykh Ṣan‘ān is so beside himself with love for a Christian maiden that he even tends her swine, and in Rūmī's poetry the ‘Franks’ who brought pigs to the sacred city of Jerusalem occur more than once.55 With the deeply-rooted aversion of Muslims to pork and to pigs, it comes as a true cultural shock for parents when their children, in British or American schools, have to learn nursery rhymes about ‘three little piggies’, illustrated by pretty drawings, or are sometimes offered innocent marzipan pigs.

The Muslims have devoted a good number of scholarly and entertaining works to zoology, for example al-Jāḥiẓ's and Damīrī's works; but on the whole the characteristics of animals were provided either by the rare allusions in the Koran or, after the eighth century, by Bidpai's fables known as Kalīla wa Dimna, which became widely read in the Islamic world after Ibn al-Muqaffa‘(d. 756) had first rendered them into Arabic.

The Koran (Sūra 2:26) mentions the tiny gnat as an example of God's instructing mankind by means of likenesses. In the Tales of the Prophets, we learn that it was a gnat that entered Pharaoh's brains, thus causing his slow and painful death—the smallest insect is able to overcome the mightiest tyrant. The bee (Sūra 16:68) is an ‘inspired’ animal whose skill in building its house points to God's wisdom. In later legend, ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib appears as the amīr an-naḥl, ‘the Prince of the bees’ because they helped him in a battle, and popular tradition in both medieval Turkey and Indo-Pakistan claims that honey becomes sweet only when the bees constantly hum the ṣalawāt-i sharīfa, the blessings over the Prophet, while gathering the otherwise tasteless sap.56

The ant appears in Sūra 27:18ff., a weak creature which was nevertheless honoured by Solomon, and the legend that it brought a locust's leg to the mighty king is often alluded to—‘a locust's leg’ is an insignificant but well-intended gift from a poor person. The spider, on the one hand, is a creature that builds ‘the weakest house’ (Sūra 29:41), and yet it was a spider that helped the Prophet during his hegira: when he spent the night with Abū Bakr in a cave, the spider wove its web so deftly over the cave's entrance that the Meccans who pursued the Prophet failed to recognize his hiding-place. So legend tells.

Although not mentioned in the Koran, the moth or butterfly that immolates itself in the candle's fire was transformed into a widespread symbol of the soul that craves annihilation in the Divine Fire. It reached Western literature through Goethe's adaptation of the motif in his poem Selige Sehnsucht.57

As for the quadrupeds, the tide of Sūra 2, Al-Baqara ‘The Cow’, is taken from the sacrifice of a yellow cow (Sūra 2:67ff.) by Moses; but during a religious discussion at Emperor Akbar's court in 1578, a pious Hindu happily remarked that God must have really loved cows to call the largest chapter of the Koran after this animal—an innocent misunderstanding that highly amused the Muslim courtiers.58

The lion, everywhere the symbol of power and glory, appears in the same role in Muslim tradition, and ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib, whose proper name was first Ḥaydara (or Ḥaydar), ‘Lion’, was praised from early days as the ‘lion of God’ and therefore surrounded by numerous names that point to his leonine qualities, such as Ghaḍanfar, ‘lion’, or Asadullāh, ‘God's lion’, or in Persian areas ‘Alīshīr, and under Turkish influence Aslan ‘Ali and ‘Ali Arslan (both shīr and arslan mean ‘lion’). The true saint, it is said, is like the golden lion in the dark forest of this world, and fierce lions bow before him or serve him as obedient mounts. But perhaps the most moving role of the lion is found in Rūmi's Fīhi mā fīhi. People travelled from near and far to see a famous strong lion, but nobody dared to come close to him from fear; however, if anyone had stroked him, he would have been the kindest creature imaginable. What is required is absolute faith, then there is no danger any more.

In popular belief, the cat is the lion's aunt, or else she is born from his sneezing.59 The Prophet's fondness for cats is often referred to, and whether or not the ḥadīth that ‘Love of cats is part of faith’ is genuine, it reflects the general feeling for the little feline. For the cat is a clean animal; her presence does not annul ritual prayer, and the water from which she has drunk can still be used for ablution. There are variants of the story of how Abū Hurayra's cat, which he always carried in his bag, saved the Prophet from an obnoxious snake, whereupon the Prophet petted her so that the mark of his fingers is still visible in the four dark lines on most cats’ foreheads, and, because the Prophet's hand had stroked her back, cats never fall on their backs. Whether the custom that a ‘Mother of cats’ and later the ‘Father of cats’ accompanied the Egyptian maḥmal on the pilgrimage to Mecca is a dim survival of the ancient Egyptian cat cult is not clear.60 Love of cats is particularly evident in Maghribi tradition, where, among the Heddawa for example, the novices are called quēṭāṭ, ‘little tom-cats’. Ibn Mashīsh is credited with love of cats, and there is also an old Sufi shrine in Fez called Zāwiya Bū Quṭūṭ, ‘that of the father of cats’, just like Pisili Sultan, ‘Lady with kitten’, in Anatolia. Yet, despite the cat's positive evaluation in early literature, there is no dearth of stories (especially in Persian) about hypocritical cats which, while peacefully murmuring their prayers or the dhikr, never forget to kill the mice which they have cheated by their alleged repentance from bloodshed.

While the cat is a clean animal, the dog is regarded as unclean, and his presence spoils the ritual prayer. He appears as fierce and greedy (anyone who has encountered the street dogs in Anatolia will appreciate this remark), and thus the dog could represent the nafs, the lower soul ‘which incites to evil’ (Sūra 12:53). Sufis were seen with a black dog besides them, which was explained to the onlooker as the hungry nafs; but, as the dog can be trained and become a kalb mu‘allam, an ‘instructed dog’, thus the lower faculties too can be turned into something useful. On the other hand, the Koran mentions the dog that faithfully kept company with the Seven Sleepers (Sūra 18:18–22), and this legendary creature, called Qiṭmīr in legends, became a symbol of fidelity and trustworthiness. The poets would love to be ‘the dog of fidelity’ at their beloved's door or, in Shia Islam, at the shrine of an imam. By unswervingly watching there, they hoped to be purified as was the dog of the Seven Sleepers, who was honoured by being mentioned in the sacred Book. The proper name Kalb ‘Alī, ‘‘Alī's dog’, in some Shia families expresses this wish. And when poets tell how the demented lover Majnūn used to kiss the paws of the cur that had passed through the quarter of his beloved Laylā, they mean to point out mat even the lowliest creature can become a carrier of blessings by his association with the beloved.61 The remarkable amount of positive allusions to dogs in Persian poetry (contrary to the rather negative picture of cats in the same literature) may stem from the Zoroastrian love for dogs which, in the dualistic Zoroastrian system, belonged to the good side of creation.

The camel, mentioned as sign of God's creative power in Sūra 88:17 (‘Don't they look at the camel how it was created?’) became in later tradition a fine symbol of the nafs which, restive and selfish in the beginning, could be educated (similar to the dog) to carry the seeker to his goal, the Divine Presence, dancing on the thorny roads despite its heavy burden when listening to the driver's song.

Among the negative animals represented in the Koran is the donkey, whose braying ‘is the ugliest possible voice’ (Sūra 31:19) and whose stupidity is understood from the remark that the ignorant who are unable to understand and appreciate the contents of the sacred scriptures are like ‘the donkey that carries books’ (Sūra 62:5). In legend, the donkey is said to be accursed because Iblīs managed to enter Noah's Ark by clinging to its tail. Traditionally, the donkey is connected in Islamic literature (as in classical antiquity) with dirt and sensuality and became, in mystical parlance, the representative of the material world which has to be left behind, just as Jesus's donkey remained on earth while he was uplifted to heaven.62

There is, however, the white mule Duldul (the name means ‘large hedgehog’) which the Prophet gave to ‘Alī and on which he performed many of his heroic deeds. Nowadays, Duldul's pictures can be found on the walls of shrines and on cheap prints in India and Pakistan to bring blessing to the building and to its owner.

The horse is the typical Arabic animal, created, according to a myth, from the swift southern wind, and Arabic literature abounds with praises of the beautiful creature. The beginning of Sūra 100 speaks of the ‘running horses’ which appear as galloping through the world towards the final goal—the Day of Judgment. But it rarely appears in truly religious contexts, although it may serve in the Sufi tradition again as a nafs-animal, which has to be starved and broken in order to become useful for its owner; the numerous allusions to the ‘restive horse’ and the miniature drawings of starved horses seem to be related to this concept.63 In Shia circles, it is believed that a white horse will carry the Mahdi when he descends to earth at the end of time; therefore a fine steed with henna-coloured feet is led every year in the Muḥarram procession (the so-called dhū ’l-janāḥ) to make sure that his horse is saddled in case he should suddenly appear. It is touched by the pious for the sake of blessing.

A strange mount, smaller than a horse and larger than a mule, was Burāq (connected with barq, ‘lightning’), that carried the Prophet during his mi‘rāj through the heavens into the Divine Presence. It is described as having a woman's face and a peacock's tail, and was the embodiment of swiftness and beauty. Poets and painters have never tired of describing it with new colourful details. Burāq nowadays appears frequently on pictures; and, in the eastern lands of the Muslim world, especially in Pakistan, trucks and buses are decorated with its ‘likeness’, perhaps in the hope that its baraka will bring the vehicle as swiftly to its goal as the real Burāq carried the Prophet through the universe.64

Serpents, so important in the Christian tradition, do not play a central role in Islam. The Koran (Sūra 7:117, 20:66ff.) alludes to Moses’ rod that turned into a serpent to devour the rods of Pharaoh's sorcerers. For they can appear as nafs-animals which are blinded by the spiritual master, who resembles an emerald.65 Also, it was Iblīs in the shape of a small snake which, carried into Paradise owing to the peacock's negligence, induced Adam and Eve to eat from the forbidden fruit. However, the role of the snake and its greater relative, the dragon, is not as central as one would expect. Yet, both snakes and dragons (the latter appearing more frequently in the indigenous Persian tradition) are connected in popular belief with treasures which they guard in ruined places. Perhaps that connects them with the mighty serpent which, according to the Tales of the Prophets, surrounds the Divine Throne.

Much more important in symbolic language is the world of birds, which, like everything, adore the Lord and know their laud and worship, as the Koran states (Sūra 24:41). The soul bird, common in early and ancient societies, was well known in the Islamic world. Pre-Islamic Arabs imagined soul birds fluttering around a grave. Later, the topic of the soul bird, so fitting to symbolize the soul's flight beyond the limits of the material world, permeates mystical literature, and still today one can hear in some Turkish families the expression Can kusu uçtu, ‘his/her soul bird has flown away’, when speaking of someone's death. The tradition according to which the souls of martyrs live in the crops of green birds to the day of Resurrection belongs in this connection.66

Again, just as plants in general play a considerable role in Islamic beliefs and folklore and yet some special plants are singled out for their religious or magic importance, the same is the case with birds. If the rose is the supreme manifestation of Divine beauty or the symbol of the beloved's cheek, then the nightingale is the soul bird par excellence. It is not only the simple rhyme gul-bulbul, ‘rose-nightingale’, in Persian that made this bird such a favourite of poets, but the plaintive nightingale which sings most expressively when roses are in bloom could easily be interpreted as the longing soul. This idea underlies even the most worldly-looking use of this combination—unbeknown to most authors.

The falcon is a different soul bird. Its symbolic use is natural in a civilization where falconry was and still is one of the favourite pastimes. Captured by a cunning old crone, Mistress World, the falcon finally flies home to his owner; or else the hard, seemingly cruel education of the wild, worthless fledgling into a well-trained hunting bird can serve as a model for the education which the novice has to undergo. The Sufis therefore liked to combine the return to his master's fist of the tamed, obedient bird with the Koranic remark (Sūra 89:27–8) ‘Return, oh you soul at peace…’, for the soul bird has undergone the transformation of the nafs ammāra into the nafs muṭma'inna. On the other hand, however, the falcon as a strong, predatory bird can also serve to symbolize the irresistible power of love or Divine grace, which grasps the human heart as a hawk carries away a pigeon.

The pigeon, or dove, is, as in the West, a symbol of loving fidelity, which is manifested by its wearing a collar of dark feathers around its neck—the ‘dove's necklace’.67 In the Persian tradition, one hears its constant cooing kū, kū, ‘Where, where [is the beloved]?’ (In India, the Papiha bird's call is interpreted similarly as Piū kahān, ‘Where is the beloved?’)

The migratory stork is a pious bird who builds his nest preferably on minarets. Is he not comparable, in his fine white attire, to pilgrims travelling once a year to Mecca? And his constant laklak is interpreted as the Arabic al-mulk lak, al-‘izz lak, al-ḥamd lak, ‘Thine is the kingdom, Thine is the glory, Thine is the praise’.

Similarly the rooster, and in particular the white rooster, is regarded as the bird who taught Adam how and when to perform the ritual prayer; thus he is sometimes seen as the muezzin to wake up the sleepers, a fact to which a ḥadīth points (AM no. 261); Rūmī even calls him by the Greek word angelos, ‘an angel’.68

The peacock, due to whose negligence the serpent, i.e. Satan, was carried into Paradise, is a strange combination of dazzling beauty and ugliness: although his radiant feathers are put as bookmarks into copies of the Koran, the ugliness of his feet and his shrieking voice have always served to warn people of selfish pride. While some authors dwell upon his positive aspects as a manifestation of the beauty of spring or Divine beauty, others claim that the bird is loved by Satan because of his assistance in bringing him into the primordial Paradise. Nevertheless, peacocks—sacred to Sarasvati in former times—are kept in many Indo-Pakistani shrines. Hundreds of them live around a small shrine in Kallakahar in the Salt Range; and in other places, peacock feathers are often used to bless the visitor.

Like the peacock, the parrot, probably unknown in early Islamic times, belongs to India and has brought from his Indian background several peculiarities: he is a wise though somewhat misogynistical teacher69 whose words, however, are sweet like sugar. That is why, in Gulbarga, deaf or stuttering children are brought to the minute tomb of a pet parrot of the saint's family; sugar is placed on the tomb, and the child has to lick it. The parrot's green colour connects him with Paradise, and it is said that he learns to speak by means of a mirror behind which someone utters words (see below, p. 31).

In the Muslim tradition of India, one sometimes encounters the hāns, the swan or, rather, large gander who, according to folk tales and poems, is able to live on pearls. Diving deep, he dislikes the shallow, muddy water—like the perfect saint who avoids the dirty, brackish water of this world.

Muslim authors’ interest in birds can be easily understood from the remark in Sūra 27:16 according to which Solomon was acquainted with the ‘language of the birds’, Manṭiq uṭ-ṭayr. This could easily be interpreted as the language of the souls, which only the true master understands. The topic of the soul birds had already been used in Ibn Sīnā's (d. 1037) Risālat aṭ-ṭayr and his poem on the soul, and Sanā'ī (d. 1131) has described and interpreted in his long qaṣīda, Tasbīḥ aṭ-ṭuyūr ‘The birds’ rosary’, the different sounds of the birds. The most extensive elaboration of the stories of the soul birds is given in ‘Aṭṭār's Manṭiq uṭ-ṭayr: the hudhud, the hoopoe, once the messenger between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, leads them through the seven valleys in their quest for the Sīmurgk.70

However, it becomes clear from ‘Aṭṭār's epic, as from other poems such as some of Nāṣir-i Khusraw's qaṣīdas, that by no means all birds are examples of the positive aspects of the human soul.71 Some are connected with the hibernal world of matter, like the crow and the raven which inhabit ruins and, contrary to other birds, enjoy the winter, the time when the world seems to be dead and the life-giving water is frozen. Was it not the raven that showed Cain how to bury his slain brother Abel (Sūra 5:31)?

Mythical birds are not lacking in Muslim lands. There is the Humā, the shade of whose wings conveys kingdom to the one touched by it, and the ‘Anqā, the ‘long-necked’ female bird which has become a metaphor for something nonexistent: adĭ var özü yok, ‘He has a name but no reality’, as the Turkish saying goes. Its Persian counterpart, the Sīmurgh, was a resourceful bird in early Persian tradition, rescuing, as the Shāhnāma has it, little Zāl and bringing the outcast child up with her own chicks; the colourful feather which she gave to Zāl allows its owner to perform licit magic. The Sīmurgh was, however, transformed into a symbol of the Divine by Suhrawardī the Master of Illumination (d. 1191) and by ‘Aṭṭār, who invented the most ingenious pun in Persian mystical literature: the thirty birds, sī murgh, who have completed their pilgrimage through the seven valleys, discover that the goal of their quest, the divine Sīmurgh, is nothing but themselves, being sī murgh.

The Koran mentions (Sūra 5:60) the transformation of sinners into pigs and monkeys, and some medieval authors took over these ideas, beginning, it seems, with the Ikhwān aṣ-ṣafā of Basra. Ghazzālī mentions the ‘animal traits’ (pig = appetite, greed; dog = anger) in his Ihyā ‘ulūm ad-dīn,72 and the Divine threat that greedy, dirty and sensual people will appear on Doomsday in the shape of those animals which they resembled in their behaviour is quite outspoken in the works of Sanā'ī and ‘Aṭṭār, and somewhat softened in some of Rūmī's verses.

Yet, there is still another side to animals in Islamic tradition. Muslim hagiography is replete with stories that tell of the love that the ‘friends of God’ showed to animals, and kindness to animals is recommended through moving stories in the ḥadīth. Early legend tells of Sufis who were famed for their loving relations with the animals of the desert or the forest, and later miniature paintings often show the saints with tame lions (or their minor relatives, namely cats) or surrounded by gazelles which no longer shy away from them. For the one who has subdued the animal traits in his soul and has become completely obedient to God will find that everything becomes obedient to him.

Finally, the dream of eschatological peace involves the idea that ‘the lion will lie down with the lamb’, and Muslim authors too have described the peaceful kingdom which will appear (or has already appeared) under the rule of this or that just and worthy sovereign, or else which will be realized in the kingdom of the Beloved.73

MAN-MADE OBJECTS